Arch Iran Med. 27(7):350-356.

doi: 10.34172/aim.28887

Original Article

Causes of Colectomy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Findings from an Iranian National Registry

Zahra Momayez Sanat Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, 1

Homayoon Vahedi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 1

Reza Malekzadeh Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 1

Amir Kasaeian Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 2, 3, 4

Negar Mohammadi Ganjaroudi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 5

Alireza Sima Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 6

Fariborz Mansour Ghanaei Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 7

Mohammadreza Ghadir Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 8

Hafez Tirgar Fakheri Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 9

Siavosh Nasseri Moghaddam Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 1

Sudabeh Alatab Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Anahita Sadeghi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 1

Amir Anushiravani Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 1

Iradj Maleki Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 9

Abbas Yazdanbod Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 10

Hassan Vossoughinia Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 11

Mohammadreza Seyyedmajidi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 12

Sayed Jalaleddin Naghshbandi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 13

Nadieh Baniasadi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 14

Baran Parhizkar Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 13

Saied Matinkhah Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 15

Shahsanam Gheibi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 16

Roya-sadat Hosseini Hemmat Abadi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 17

Seyedmohamad Valizadeh Toosi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, 9

Author information:

1Digestive Disease Research Center, Digestive Disease Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Digestive Oncology Research Center, Digestive Diseases Research Institute, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Research Center for Chronic Inflammatory Diseases, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4Clinical Research Development Unit, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

6Sasan Alborz Biomedical Research Center, Masoud Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Tehran, Iran

7Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Guilan, Iran

8Gastroenterology and Hepatology Diseases Research Center, Qom University of Medical Science, Qom, Iran

9Gut and Liver Research Center, Non-communicable Diseases Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

10Digestive Diseases Research Center, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran

11Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

12Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology, Golestan University of Medical Science, Gorgan, Iran

13Liver and Digestive Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

14Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

15Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

16Maternal and Childhood Obesity Research center, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

17Shahid Sadoughi University, Yazd, Iran

Abstract

Background:

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) marked by rectal and colon inflammation, leading to relapsing symptoms. Its prevalence is increasing, particularly in developed nations, impacting patients’ health. While its exact cause remains unclear, genetic and environmental factors are implicated, elevating the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Colectomy, though declining, is still performed in select UC cases, necessitating further study.

Methods:

We analyzed data from the Iranian Registry of Crohn’s and Colitis (IRCC) to examine UC patients undergoing colectomy. We collected demographic and clinical data from 91 patients, focusing on dysplasia. Statistical analyses assessed dysplasia risk factors.

Results:

Patients with dysplasia were older at diagnosis and surgery compared to those without dysplasia. Age emerged as a significant risk factor for dysplasia in UC patients undergoing colectomy. No significant associations were found between dysplasia and other factors.

Conclusion:

Age plays a crucial role in dysplasia risk among UC patients undergoing colectomy. Older age at diagnosis and surgery may indicate a higher risk of dysplasia and CRC. Clinicians should consider age when managing UC patients and implementing screening protocols. Further research with larger samples is needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Colectomy, Dysplasia, Ulcerative colitis

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Momayez Sanat Z, Vahedi H, Malekzadeh R, Kasaeian A, Mohammadi Ganjaroudi N, Sima A, et al. Causes of Colectomy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Findings from an Iranian National Registry. Arch Iran Med. 2024;27(7):350-356. doi: 10.34172/aim.28887

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) stands as a distinctive subtype within the spectrum of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), characterized by initial involvement of the rectum, often progressing contiguously to affect the colon.1 Lesions characteristic of UC manifest superficially, with inflammation predominantly confined to the mucosal and submucosal layers.2 UC occurs in a relapsing and remitting form.3 Patients with UC can present with intestinal manifestations such as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, and fecal urgency, or extra-intestinal symptoms such as musculoskeletal, cutaneous, and hepatobiliary manifestations.4,5

Over recent years, the prevalence of UC has witnessed a surge, with North America and Europe registering the highest prevalence rate.6-8 Moreover, increased prevalence of UC has been reported in industrialized countries.9,10 Previous studies have reported UC prevalence and incidence ranging from 7.6 to 245 and 1.2 to 20.3 cases per 100 000 individuals per year, respectively.11-14 The exact etiologies of UC are unknown, but it is believed that genetics play an essential role in the development of the disease.15 Reports indicate a four-fold higher risk of UC among first-degree relatives of affected individuals.14 Additionally, environmental factors exert significant influence on UC progression, with diet, certain medication use, vitamin D levels, stress, and smoking history implicated as potential risk factors.16 UC is associated with an increased risk of malignancies.17 Estimates suggest a progressive increase in colorectal cancer (CRC) risk with disease duration, reaching 2%, 8%, and 18% at 10, 20, and 30 years, respectively.18 Notably, CRC accounts for a significant proportion (10‒15%) of mortality in IBD cases.19 Risk factors for CRC in UC patients include disease extent, duration, concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis, and family history of CRC.18,20-22

Although the development of new biologic therapies has reduced the need for surgical procedures, a significant number of patients still undergo operations such as colectomy.23-28 Indications for colectomy include failure of medical therapy, increased risk of cancer, fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, and intensive extra-intestinal manifestations.29

The Iranian Registry of Crohn’s and Colitis (IRCC) is a multicenter prospective registry that aims to provide a better understanding of the natural history, phenotype, treatment response, complications, and survival of IBD patients in Iran.30 The colectomy data from this registry have not been reported previously. In this regard, in the current study, we retrospectively examined the baseline characteristics and the presence of identified risk factors for colectomy among all UC patients in the IRCC database.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

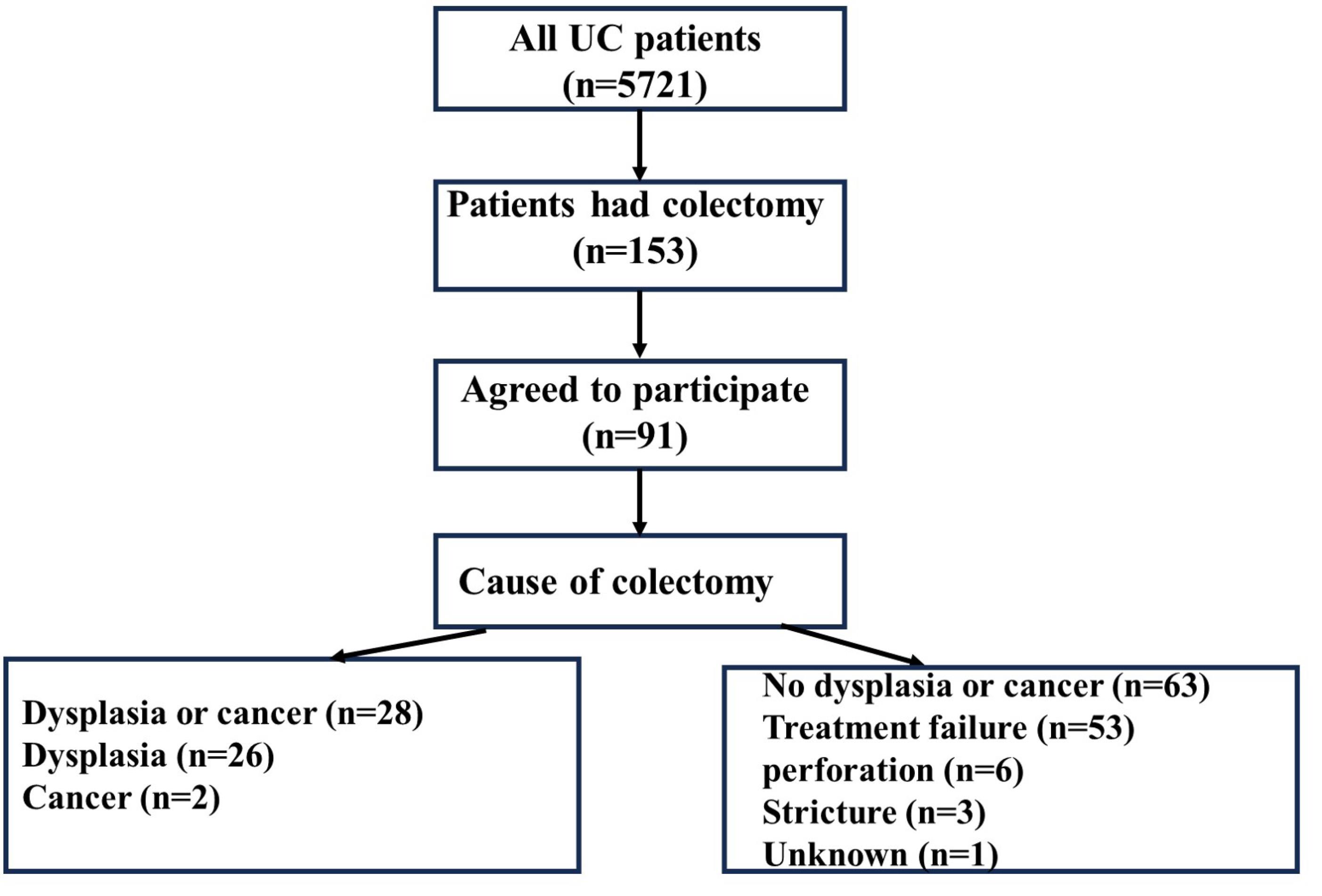

The present study is a cross-sectional, national registry-based study that includes all patients with an established UC diagnosis who were registered in IRCC. UC diagnosis was based clinical, radiological, colonoscopic, and pathologic findings according to international guidelines for IBD diagnosis. The detail of IRCC has been published elsewhere.30 In this registry, a total of 5721 UC patients were enrolled between 2017 and 2022. Among them, 153 patients underwent colectomy, with 91 of these individuals consenting to participate in the present study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the included patients

.

Flowchart of the included patients

Study Participation and Data Collection

This study targeted UC patients aged 18 or higher who had undergone colectomy regardless of reason. After obtaining informed consent from the patients, demographic and clinical characteristics were collected from medical records. The collected information included demographic characteristics, disease extent, extra-intestinal manifestations, IBD medication history, cause of colectomy, and type of colectomy (elective vs emergency).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16. Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation, were utilized for reporting quantitative variables. The chi-square test was employed for categorical variables, while the independent t test was used for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression was conducted to assess differences between the two groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

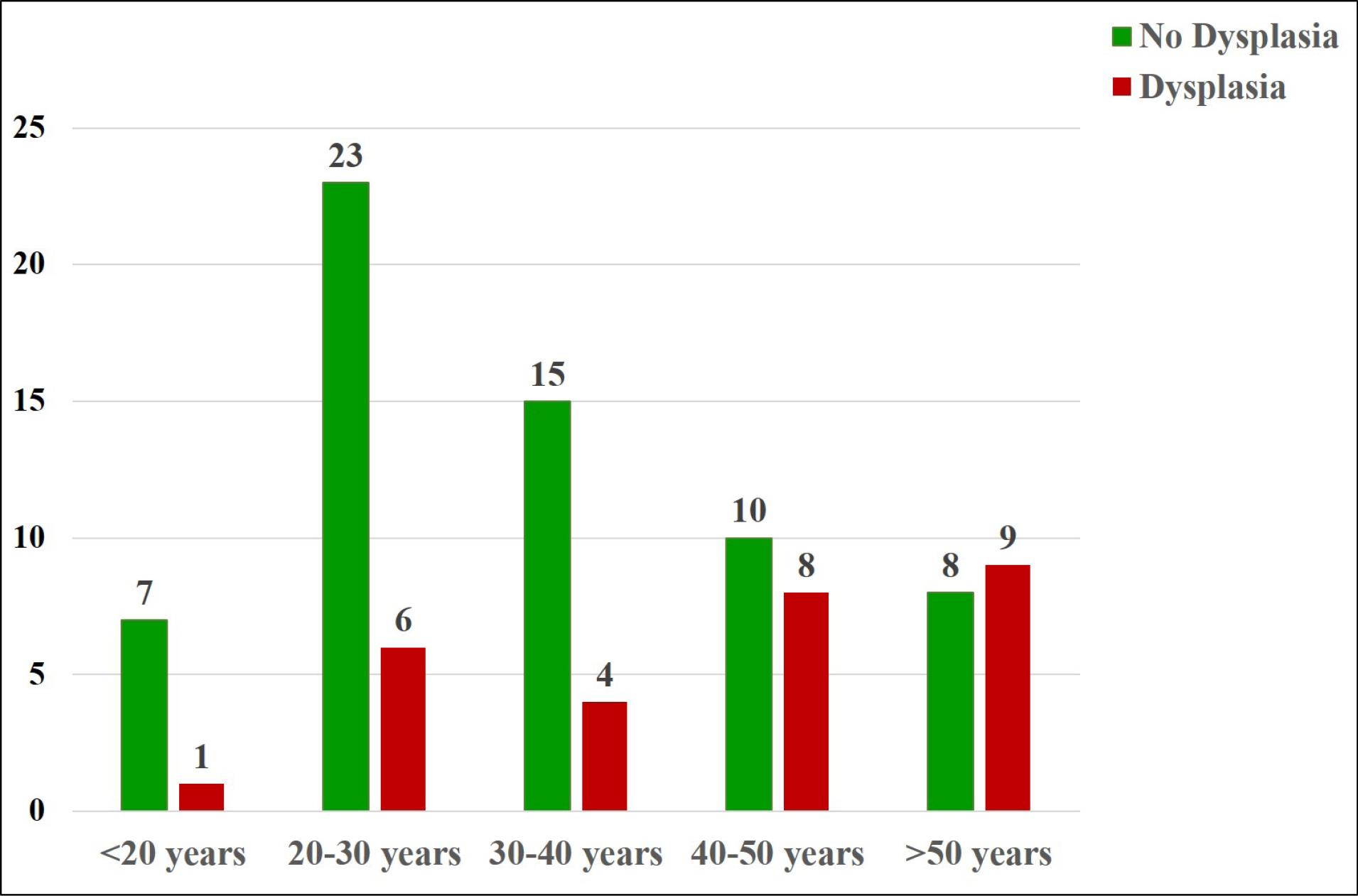

The patients’ flowchart, illustrated in Figure 1, outlines the enrollment process, culminating in the inclusion of 91 UC patients in our study. Among these participants, 49 (55.6%) were male. Of the 91 patients admitted, 28 were diagnosed with cancer or dysplasia, while 63 were not. Among the 63 patients whose colectomy was not attributed to dysplasia, 53 (83.9%) experienced treatment failure, 6 (9.4%) encountered perforation, 3 (4.6%) developed strictures, and 1 (1.2%) had an indeterminate cause. The mean age of participants was 54.3 ± 13.6 years in the dysplasia group and 43.6 ± 12.1 years in the non-dysplasia group. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the two study groups based on cause of colectomy (dysplasia vs non-dysplasia), while Figure 2 delineates the age at diagnosis distribution of the two study groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

|

Variable

|

All Cases with Colectomy (n=91)

|

P

Value

|

|

No Dysplasia (n=63)

|

Dysplasia (n=28)

|

| Age |

< 55 years |

51 |

15 |

< 0.001 |

| > 55 years |

12 |

13 |

| BMI |

Mean (SD) |

24.5 (3.4) |

25.7 (3.1) |

0.35 |

| Age at diagnosis |

Mean (SD) |

29.2 (12.1) |

36.2 (14.1) |

< 0.001 |

| Duration of disease |

Mean (SD) |

14.5 (8.6) |

18.1 (8.7) |

0.077 |

| Gender |

Male |

33 |

17 |

0.46 |

| Female |

30 |

11 |

| Marital status |

Single |

10 |

3 |

0.74 |

| Married |

52 |

25 |

| Education level |

Less than 12 years |

8 |

9 |

0.09 |

| 12 years |

32 |

11 |

| More than 12 years |

23 |

8 |

| Ethnicity |

Persian |

44 |

24 |

0.43 |

| Kurd |

1 |

1 |

| Lor |

6 |

1 |

| Turk |

11 |

2 |

| Baluch |

1 |

0 |

| Blood group |

A |

19 |

7 |

0.66 |

| AB |

3 |

1 |

| B |

14 |

6 |

| O |

20 |

9 |

| Unknown |

6 |

4 |

| Extension of disease |

Left colitis |

4 |

2 |

0.96 |

| Pancolitis |

56 |

23 |

| Unknown |

2 |

1 |

| UC diagnosis |

Inpatient |

8 |

4 |

0.83 |

| Outpatient |

55 |

24 |

| Type of colectomy |

Elective |

57 |

26 |

0.99 |

| Emergent |

6 |

2 |

| Smoking |

Yes |

9 |

7 |

0.36 |

| No |

54 |

21 |

| Opium use |

Yes |

1 |

1 |

0.55 |

| No |

62 |

27 |

| Alcohol use |

Yes |

3 |

1 |

0.81 |

| No |

60 |

27 |

| History of blood transfusion |

Yes |

45 |

12 |

0.12 |

| No |

18 |

16 |

| History of CMV colitis |

Yes |

2 |

0 |

0.34 |

| No |

61 |

28 |

| Family history of UC |

Yes |

21 |

7 |

0.42 |

| No |

42 |

21 |

Figure 2.

Age at diagnosis

.

Age at diagnosis

Table 2 delineates the pharmacological regimens administered to the patients. Interestingly, no significant difference was observed between patients whose initial treatment involved biological agents and those who received other medications. Furthermore, no statistically significant association was found between the duration of medication use and the occurrence of dysplasia. Mesalazine emerged as the most commonly prescribed initial drug, with a notable proportion of patients with dysplasia having received this medication. Among those who progressed to the second and third stages of drug therapy, none of the six individuals treated with Infliximab were diagnosed with dysplasia. Conversely, only one out of fifteen patients who received Azathioprine exhibited dysplasia. The primary reason for transitioning from the initial drug regimen was treatment failure in 44 patients, while adverse drug reactions prompted a change in medication for 11 individuals, and non-compliance was cited as the reason in 2 cases.

Table 2.

Treatment Steps of the Study Population

|

Steps of Treatment

|

Dysplasia

|

No Dysplasia or Cancer

|

| First |

| Azathioprine |

2 |

0 |

| Mesalazine |

52 |

20 |

| Sulphasalazine |

8 |

5 |

| Second |

| Azathioprine |

10 |

1 |

| CinnoRA® |

4 |

4 |

| Infliximab |

5 |

0 |

| Mesalazine |

5 |

3 |

| Sulphasalazine |

8 |

1 |

| Third |

| Azathioprine |

2 |

0 |

| CinnoRA® |

5 |

1 |

| Infliximab |

1 |

0 |

Table 3 show the extra-intestinal manifestations in the two groups. Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups in any of the extra-intestinal manifestations.

Table 3.

Comparison of Extra-intestinal Manifestations in the Two Groups

|

Extra-Intestinal Manifestation

|

Dysplasia (n=28)

|

No Dysplasia (n=63)

|

P

Value

|

| Articular disease |

1 (3.8) |

2 (7.6) |

0.941 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis |

1 (3.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0.248 |

| Ophthalmologic disease |

1 (3.8) |

3 (4.8) |

0.857 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

2 (7.6) |

2 (3.2) |

0.578 |

| Perianal abscess |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.6) |

0.928 |

According to the findings derived from the univariate analysis, as depicted in Table 4, several factors were found to be significantly correlated with an increased risk of dysplasia or cancer in UC patients undergoing colectomy. Notably, age (OR = 1.06), age at the time of diagnosis of the disease (OR = 1.04), and age at the time of surgery (OR = 1.06) demonstrated statistically significant associations with the heightened risk of dysplasia or cancer.

Table 4.

Results of Univariate Analysis

|

Factor

|

Odds Ratio

|

95 % CI

|

P

Value

|

| Age |

1.06 |

1.02‒1.11 |

0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis |

1.04 |

1.00‒1.08 |

0.019 |

| Age at surgery |

1.06 |

1.02‒1.11 |

0.002 |

| Gender (Male/Female) |

1.40 |

0.55‒3.57 |

0.475 |

| Duration of disease |

2.61 |

0.98‒6.78 |

0.07 |

| Marital status (Married/Single) |

1.47 |

0.37‒5.86 |

0.581 |

| Education Level |

0.87 |

0.73‒1.03 |

0.123 |

| Body mass index |

1.11 |

0.96‒1.28 |

0.135 |

| Smoking (Yes/No) |

1.76 |

0.55‒5.60 |

0.361 |

| Non steroid anti- inflammatory drugs (Yes/No) |

1.25 |

0.41‒3.78 |

0.774 |

However, other demographic and clinical variables, including gender (OR = 1.40), marital status (OR = 1.47), duration of disease (OR = 2.61), education level (OR = 0.87), BMI (OR = 1.11), smoking (OR = 1.76), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, did not exhibit a significant association with dysplasia in UC patients undergoing colectomy.

Discussion

UC is a subgroup of IBD, which causes inflammation, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and increased epithelial cell turnover, resulting in low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and consequently CRC.31-33 The relationship between UC and CRC has been established in previous studies.18,34,35 The prevalence of CRC in UC patients was reported at 3.7%36; however, in our study, the prevalence of colorectal dysplasia and cancer was 31.1%. In one meta-analysis, the incidence of CRC in UC patients was reported at 1.58 per 1000 patients per year.37 In a meta-analysis by Eaden et al, the incidence of CRC in UC patients was reported at 2%, 8% and 18% in 10 years, 20 years and 30 years, respectively.38 As a result of the occurrence of CRC, UC patients should be followed up based on surveillance protocols, although with the advent of new therapies including biologic agents, the risk of CRC in UC patients has declined.39-41 If malignant lesions are found in the follow-up tests, surgery is considered an option.28,29 Another indication for surgery in UC patients is when patients are not responding to pharmacological treatment.29,42 Although with the advent of new therapies and treatment protocols, the need for surgery has declined, a significant number of patients undergo surgery.42-44

In this study, our objective was to assess the risk factors of dysplasia in UC patients who underwent colectomy. We evaluated 12 factors, among which three factors showed significant associations with an elevated risk of neoplasia in UC patients: patient’s age, age at the time of diagnosis, and age at the time of surgery.

Based on the results of this study, UC patients who underwent colectomy due to dysplasia were significantly older than those who underwent colectomy due to other reasons. Moreover, they were significantly older at the time of diagnosis and surgery. This finding implies a higher chance of CRC in older UC patients than young ones. The results of other studies are conflicting. In a cohort study on UC patients, Gyde et al reported that the highest chance of cancer in a UC patient is expected to occur at around 50.45 In another retrospective study by Karvellas et al, UC patients diagnosed after the age of 40 were at higher risk of CRC than UC patients diagnosed before the age of 40.34 Bamba and Nishiyama showed the higher risk of CRC in elderly UC patients.46 The increased cancer risk in older patients can be attributed to lead-time bias and pathological processes. The chance of undiagnosed colitis for a longer duration is higher in older UC patients.34 Moreover, carcinogenesis processes develop at advanced ages, like DNA hypermethylation which has a potential role in colonic neoplasia.47

Our study revealed no significant association between blood group and the risk of dysplasia in UC patients. This finding aligns with research conducted by Al-Sawat, which found no statistical difference in the relationship between blood group types and CRC risk.48 Similarly, Khalil et al observed no significant difference between blood group types and the risk of CRC in their study.49

In our study, the ethnicity of the patients was not a risk factor for occurrence of dysplasia in UC. Ethnicity can play an important role in the development of UC.12,50-52 Studies showed that ethnicity can also affect the incidence and prevalence of CRC.53,54 In a study by Damas et al, the prevalence of IBD-related dysplasia was significantly affected by ethnicity.55

In our study, we did not find smoking to be a significant risk factor for dysplasia in UC patients. However, our sample size was small, so caution is advised in interpreting these results. The impact of smoking on UC remains controversial, with current smoking being potentially protective while former smoking may pose a risk.56 Smoking is thought to be a risk factor for CRC. A recent meta-analysis showed former smokers, and current smokers to be at higher risk of CRC.57 In a recent retrospective cohort study, former smokers were at increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in the UC population, while passive smoking had no significant effect.58 Due to the divergent impact of smoking on the UC severity and risk of CRC, we suggest further studies to assess the pooled results of cigarette smoking on CRC among UC patients.

In this study, positive family history of UC was not significantly associated with increased risk of CRC in UC patients. This finding is consistent with the result of a cohort study by Askling et al in which although a positive family history of CRC was associated with increased risk of CRC in the IBD population, no significant relation was found for family history of IBD.22

Our study did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of extra-intestinal manifestations of UC between patients with cancer and those without, contrary to previous findings indicating an increased cancer risk in IBD patients with extra-intestinal manifestations.59 We believe the small sample size of our study is one of the reasons which necessitate the result to be considered with caution. In addition, data of some patients were not available. We recommend more high-quality, studies with larger sample size and in multicenter settings to assess the relationship between the extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD and CRC.

Conclusion

In summary, we discovered a correlation between dysplasia and advanced age at diagnosis and operation. According to these results, older UC patients may be at increased risk of CRC. It is recommended that clinicians treat certain patient groups as high-risk individuals and that specific screening and surveillance strategies are implemented for them.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Digestive Disease Research Institute (DDRI) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for logistic support for setting up the Iranian Registry of Crohn’s and Colitis (IRCC). All authors contributed solely as volunteers. We are grateful to the employees of the IRCC cohort for their contribution to data gathering.

IRCC members that contribute to this study include:

AbdolRasool Hayatbakhsh, Abdossamad Gharavi, Afshin Shafaghi, Ali Beheshti Namdar, Amineh Hojati, Amir Hossein Faraji, Amirabbas Hasan Zadeh, Arash Kazemi Veisari, Elham Mokhtari Amirmajdi, Fatemeh Farahmand, Forough Alborzi, Hasan Ali Metanat, Hayedeh Adilipour, Hosein Alimadadi, Jalaluddin Naghshbandi, Katrin Behzad, Kourosh Mojtahedi, Ladan Goshayeshi, Mahdi Pezeshki Modares, Mahmoud Hoseinian, Mahmoud Yousefi Mashhour, Masoud Dooghaie Moghadam, Mehdi Saberi Firoozi, Mehri Najafi, Mitra Ahadi, Mohammad Reza Farzanehfar, Nadieh Baniasadi, Sahar Rismantab, Sanaz Gonoodi, Seyed Mohammad Valizadeh Toosi, Tarang Taghvaei, Vahid Hosseini, Taghi Amiriani, Abazar Parsi, Shahsanam Gheibi, Saied Matinkhah, Baran Parhizkar, Roozbeh Rabiee, Mohammadreza Seyyedmajidi, Mandana Rafeey, Ali Gavidel, Mahdi Saberi Firoozi.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the institution’s opposition but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

This study was ethically approved by the Ethics Committee of Digestive Disease Research Institute of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (reference number: IR.TUMS.DDRI.REC.1401.028). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Funding

This work was supported by Deputy of Research of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, and Digestive Diseases Research Institute (DDRI).

References

- Assadsangabi A, Lobo AJ. Diagnosing and managing inflammatory bowel disease. Practitioner 2013; 257(1763):13-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Torres J, Billioud V, Sachar DB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: the forgotten evidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18(7):1356-63. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22839 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2005; 19 Suppl A:5A-36A. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein JD, Moss AC, Farraye FA. Ulcerative colitis. Mayo Clin Proc 2019; 94(7):1357-73. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Malik TF, Aurelio DM. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Burisch J, Munkholm P. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015; 50(8):942-51. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1014407 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bedrikovetski S, Dudi-Venkata N, Kroon HM, Liu J, Andrews JM, Lewis M. Systematic review of rectal stump management during and after emergency total colectomy for acute severe ulcerative colitis. ANZ J Surg 2019; 89(12):1556-60. doi: 10.1111/ans.15075 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017; 389(10080):1756-70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32126-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morita N, Toki S, Hirohashi T, Minoda T, Ogawa K, Kono S. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Japan: nationwide epidemiological survey during the year 1991. J Gastroenterol 1995; 30 Suppl 8:1-4. [ Google Scholar]

- Subasinghe D, Nawarathna NM, Samarasekera DN. Disease characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): findings from a tertiary care centre in South Asia. J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 15(9):1562-7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1588-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(18):1713-25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Loftus EV Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(6):1504-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV Jr. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted county, Minnesota from 1970 through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15(6):857-63. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.039 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lynch WD, Hsu R. Ulcerative colitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Thompson AI, Lees CW. Genetics of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17(3):831-48. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21375 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013; 9(6):367-74. [ Google Scholar]

- Kulaylat MN, Dayton MT. Ulcerative colitis and cancer. J Surg Oncol 2010; 101(8):706-12. doi: 10.1002/jso.21505 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lakatos PL, Lakatos L. Risk for colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: changes, causes and management strategies. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(25):3937-47. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3937 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Munkholm P. Review article: the incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 18 Suppl 2:1-5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.18.s2.2.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Loftus EV Jr, Harewood GC, Loftus CG, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. PSC-IBD: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 2005; 54(1):91-6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046615 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vera A, Gunson BK, Ussatoff V, Nightingale P, Candinas D, Radley S. Colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease after liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Transplantation 2003; 75(12):1983-8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000058744.34965.38 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Askling J, Dickman PW, Karlén P, Broström O, Lapidus A, Löfberg R. Family history as a risk factor for colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2001; 120(6):1356-62. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24052 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bennis M, Tiret E. Surgical management of ulcerative colitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2012; 397(1):11-7. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0848-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vanga R, Long MD. Contemporary management of ulcerative colitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2018; 20(3):12. doi: 10.1007/s11894-018-0622-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GG, Seow CH, Ghosh S, Molodecky N, Rezaie A, Moran GW. Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(12):1879-87. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.333 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mao EJ, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG, Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Ananthakrishnan AN. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: comparative efficacy of immunosuppressants and biologics for reducing hospitalisation and surgery in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45(1):3-13. doi: 10.1111/apt.13847 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, Winther KV, Borg S, Binder V. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13(4):481-9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hefti MM, Chessin DB, Harpaz NH, Steinhagen RM, Ullman TA. Severity of inflammation as a predictor of colectomy in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52(2):193-7. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ad456 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Frizelle FA, Burt MJ. Surgical management of ulcerative colitis. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6931/.

- Malekzadeh MM, Sima A, Alatab S, Sadeghi A, Daryani NE, Adibi P. Iranian Registry of Crohn’s and Colitis: study profile of first nation-wide inflammatory bowel disease registry in Middle East. Intest Res 2019; 17(3):330-9. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.00157 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rogler G. Chronic ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett 2014; 345(2):235-41. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peixoto RD, Ferreira AR, Cleary JM, Fogacci JP, Vasconcelos JP, Jácome AA. Risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease and pitfalls in oncologic therapy. J Gastrointest Cancer 2023; 54(2):357-67. doi: 10.1007/s12029-022-00816-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology 2011; 140(6):1807-16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.057 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Karvellas CJ, Fedorak RN, Hanson J, Wong CK. Increased risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis patients diagnosed after 40 years of age. Can J Gastroenterol 2007; 21(7):443-6. doi: 10.1155/2007/136406 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yashiro M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(44):16389-97. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16389 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eaden J. Review article: colorectal carcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20 Suppl 4:24-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02046.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39(7):645-59. doi: 10.1111/apt.12651 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 2001; 48(4):526-35. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut 2004; 53(12):1813-6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038505 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chambers WM, Warren BF, Jewell DP, Mortensen NJ. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 2005; 92(8):928-36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5106 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Andersen NN, Jess T. Has the risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease decreased?. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(43):7561-8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7561 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cohen JL, Strong SA, Hyman NH, Buie WD, Dunn GD, Ko CY. Practice parameters for the surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48(11):1997-2009. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0180-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Biondi A, Zoccali M, Costa S, Troci A, Contessini-Avesani E, Fichera A. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis in the biologic therapy era. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(16):1861-70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1861 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghoz H, Kesler A, Hoogenboom SA, Gavi F, Brahmbhatt B, Cangemi J. Decreasing colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis in the past decade: improved disease control?. J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 24(2):270-7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04474-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gyde SN, Prior P, Allan RN, Stevens A, Jewell DP, Truelove SC. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study of primary referrals from three centres. Gut 1988; 29(2):206-17. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.2.206 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bamba T, Nishiyama Y. [Clinical features and management of the elderly patients with ulcerative colitis]. Nihon Rinsho 1999;57(11):2598-602. [Japanese].

- Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. Accelerated age-related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 2001; 61(9):3573-7. [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Sawat A, Alswat S, Alosaimi R, Alharthi M, Alsuwat M, Alhasani K. Relationship between ABO blood group and the risk of colorectal cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. J Clin Med Res 2022; 14(3):119-25. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4691 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khalili H, Wolpin BM, Huang ES, Giovannucci EL, Kraft P, Fuchs CS. ABO blood group and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20(5):1017-20. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-10-1250 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142(1):46-54.e42. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001.

- Ahuja V, Tandon RK. Inflammatory bowel disease in the Asia-Pacific area: a comparison with developed countries and regional differences. J Dig Dis 2010; 11(3):134-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00429.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hou JK, El-Serag H, Thirumurthi S. Distribution and manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(8):2100-9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.190 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Carethers JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Adv Cancer Res 2021; 151:197-229. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2021.02.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Petrick JL, Barber LE, Warren Andersen S, Florio AA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Racial disparities and sex differences in early- and late-onset colorectal cancer incidence, 2001-2018. Front Oncol 2021; 11:734998. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.734998 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Damas OM, Raffa G, Estes D, Mills G, Kerman D, Palacio A. Ethnicity influences risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-associated colon cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of dysplasia prevalence and risk factors in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites with IBD. Crohns Colitis 360 2021; 3(2):otab016. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otab016 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bastida G, Beltrán B. Ulcerative colitis in smokers, non-smokers and ex-smokers. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(22):2740-7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i22.2740 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2009; 124(10):2406-15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24191 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- van der Sloot KW, Tiems JL, Visschedijk MC, Festen EA, van Dullemen HM, Weersma RK, et al. Cigarette smoke increases risk for colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20(4):798-805.e1. 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.015.

- Wang R, Leong RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis as an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer in the context of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(27):8783-9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8783 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]