Arch Iran Med. 26(11):607-617.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.90

Original Article

Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR): Study Protocol and First Results

Monireh Sadat Seyyedsalehi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, 1, 2

Azin Nahvijou Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, 2

Shaghayegh Haghjooy Javanmard Funding acquisition, Supervision, 3

Mojtaba Vand Rajabpour Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 2

Amirreza Manteghinejad Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 4

Habibollah Pirnejad Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 5, 6

Zahra Niazkhani Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 7

Arash Golpazir Sorkheh Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 8

Maryam Baniamer Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 9

Jamshid Anasari Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 10

Masoud Bahrami Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 11

Maryam Marzban Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 12, 13

Atefeh Esfandiari Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 14

Seyedeh Masoumeh Ghoreishi Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 15

Novin Nikbakhsh Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 16

Yahya Baharvand Iran Nia Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 17

Shahram Ahmadi Somaghian Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 18

Mohammad Taghi Ashoobi Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 19, 20

Fataneh Bakhshi Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 21

Alireza Ansari-Moghaddam Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 22

Mahdieh Bakhshi Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, 22

Maryam Moradi Binabaj Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 23

Hassan Nourmohammadi Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 24

Ramesh Omranipour Methodology, 25

Kazem Zendehdel Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, 2, 26, *

Author information:

1Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy

2Cancer Research Centre, Cancer Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Applied Physiology Research Center, Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan University of Medical Science, Isfahan, Iran

4Cancer Prevention Research Center, Omid Hospital, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

5Patient Safety Research Center, Clinical Research Institute, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

6Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management (ESHPM), Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

7Nephrology and kidney Transplant Research Center, Clinical Research Institute, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

8Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

9Department of Chemical Engineering, Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic), Tehran, Iran

10Depertment of Radiation Oncology, Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran

11Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran

12Clinical Research Development Center, The Persian Gulf Martyrs, Bushehr University of Medical Science, Bushehr, Iran

13Statistical Genetics Lab, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

14Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Medicine, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran

15Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

16Cancer Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

17Department of Internal Medicine, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

18Shahid Rahimi Hospital, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

19Razi Clinical Research Development Unit, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

20Guilan Road Trauma Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

21Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

22Health Promotion Research Center, Zahedan University of Medical sciences, Zahedan, Iran

23Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

24Department of Internal Medicine Shahid Mostafa Khomeini Hospital, Ilam, Iran

25Department of Surgical Oncology, Cancer Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

26Cancer Biology Research Center, Cancer Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Background:

Breast cancer (BC), as a significant global health problem, is the most common cancer in women. Despite the importance of clinical cancer registries in improving the quality of cancer care and cancer research, there are few reports on them from low- and middle-income countries. We established a multicenter clinical breast cancer registry in Iran (CBCR-IR) to collect data on BC cases, the pattern of care, and the quality-of-care indicators in different hospitals across the country.

Methods:

We established a clinical cancer registry in 12 provinces of Iran. We defined the organizational structure, developed minimal data sets and data dictionaries, verified data sources and registration processes, and developed the necessary registry software. During this registry, we studied the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cancer who were admitted from 2014 onwards.

Results:

We registered 13086 BC cases (7874 eligible cases) between 1.1.2014 and 1.1.2022. Core needle biopsy from the tumor (61.25%) and diagnostic mammography (68.78%) were the two most commonly used diagnostic methods. Stage distribution was 2.03% carcinoma in situ, 12% stage I, 44.65% stage II, 21.32% stage III, and 4.61% stage IV; stage information was missing in 1532 patients (19.46%). Surgery (95.01%) and chemotherapy (79.65%) were the most common treatments for all patients.

Conclusion:

The information provided by this registry can be used to evaluate and improve the quality of care for BC patients. It will be scaled up to the national level as an important resource for measuring quality of care and conducting clinical cancer research in Iran.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Health policy, Hospital, Quality indicator, Registry

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Seyyedsalehi MS, Nahvijou A, Haghjooy Javanmard Sh, Vand Rajabpour M, Manteghinejad A, Pirnejad H, et al. Clinical breast cancer registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR): study protocol and first results. Arch Iran Med. 2023;26(11):607-617. doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.90

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), as a significant global health issue, is the most diagnosed cancer in women with an estimated 2.3 million new cases annually, representing 25% of all cancer diagnoses among women.1 BC is one of the most diagnosed cancers in the low-, and middle-income countries, including Iran.2-5 Since the incidence and mortality rates of BC are increasing, almost all countries are facing an economic burden due to BC.2,6,7 However, the lifetime risk of developing BC differs by country and ethnicity due to exposure to different risk factors. Various factors determine the incidence and mortality rates of BC in different countries, including economic development, environmental factors, and ethnicity.6 When comparing data from developed and developing countries, differences are observed in BC incidence and mortality rates. Comparatively, developed countries display high incidence and low mortality rates of BC, whereas developing countries display low incidence and high mortality rates. The disease is most reported in Western Europe and the United States, while it is least reported in Africa and Asia, which may reflect a false prevalence.

BC prevention, lack of awareness and screening protocols, lack of or limited access to diagnostic centers in rural areas for early detection, lower standards of healthcare facilities, and improper management of diagnosed cases could have significant impact on treating this disease.7-10 Hence, the efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) are focused on three main pillars within the Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI), namely: 1) health promotion and early detection, 2) reduced delay to health system access, and 3) comprehensive BC management, particularly where cancer programs are often inaccessible and under resourced.11 For the sake of the three main GBCI programs, registries can serve as an integral part for monitoring the programs and providing evidence for informed decision makings.12,13 Furthermore, registries can affect other approaches, such as convening stakeholders and developing a platform for action and operational guidance.12 In this regard, hospital-based cancer registries have collected different data elements about BC patient management, such as diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and quality indicators.14,15

Similar to most other countries, BC is the most common cancer in Iran and annually more than 17 000 new BC cases are diagnosed.1 It is expected that the incidence rate of BC will be doubled in a decade.9 Therefore, early detection and proper management of BC is a growing public health issue. We established a multicenter clinical breast cancer registry in Iran (CBCR-IR) to collect data about BC cases, the pattern of care, and the quality-of-care indicators in different hospitals across the country. The results of this registry provide evidence for health policy making and for interventions to improve diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in hospitals, at local and national levels. In this paper, we aimed to introduce the CBCR-IR, its study protocol, and its early descriptive results during the first five years of the registry implementation.

Objectives

The main objective of this registry was to collect the hospital-based data and to evaluate the quality of BC care in Iran and compare the quality-of-care indicators in different settings in Iran. The specific objectives of the registry are:

-

To evaluate the patterns of care and benchmark the patient outcomes in different regions,

-

To evaluate the effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment rates over time,

-

To improve the quality of BC care,

-

To develop a database for clinical and epidemiological research,

-

To develop a basis for professional education.

Materials/Patients and Methods

History of the CBCR-IR Registry Design

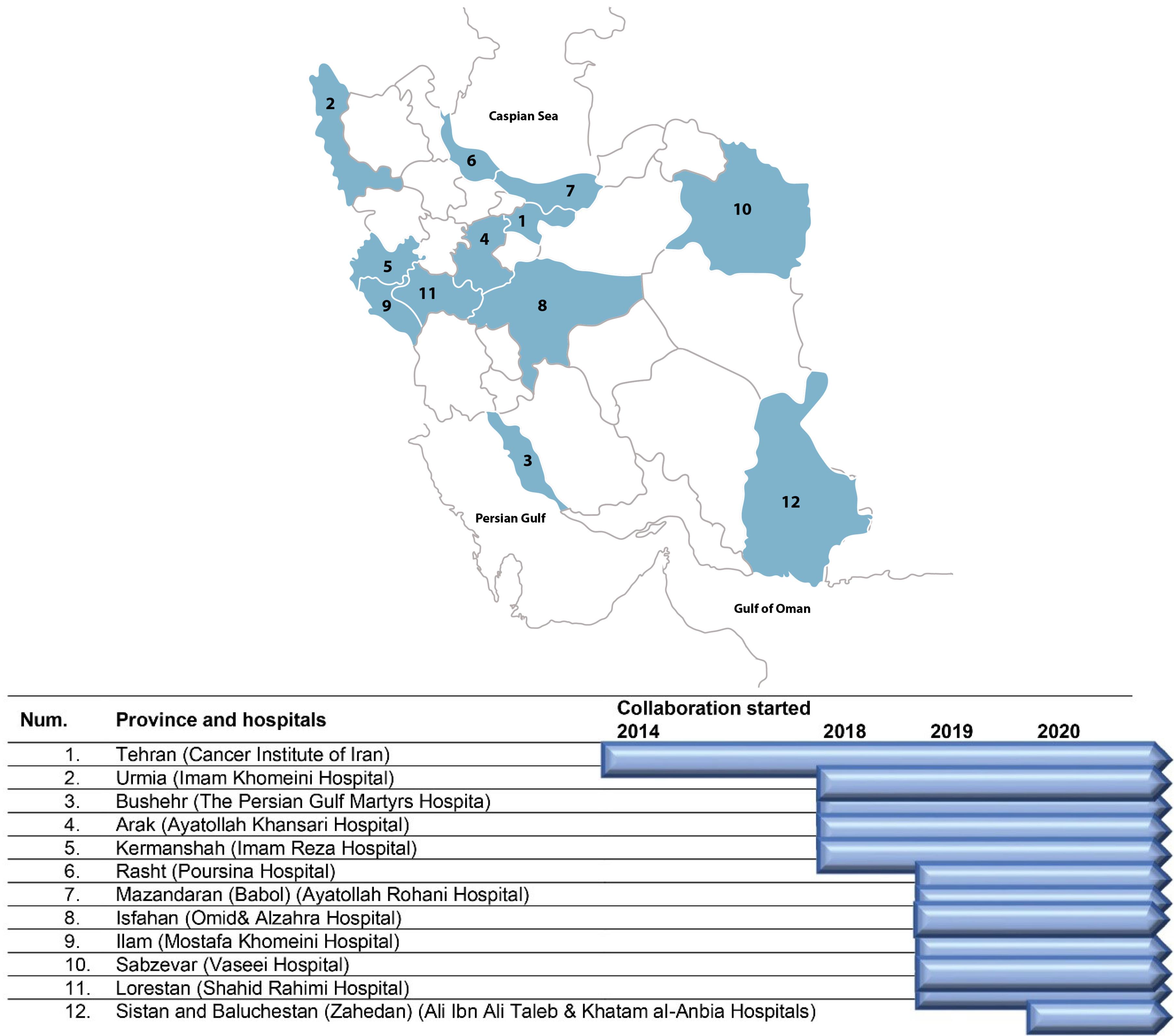

For the first time in 2012, international experts recommended establishing clinical/hospital-based cancer registries in Iran.16 The clinical cancer registry was established in 2014 in the Cancer Institute of Iran in the form of a hospital cancer registry that prioritized data on four common cancer sites in Iran, including breast, esophagus, stomach, and colorectal cancers. The details about the implementation steps and the results of the pilot phase have been published elsewhere.17 In 2018, following the successful experience of hospital cancer registry in the Cancer Institute of Iran, we designed and established a national collaboration network of oncology centers and hospitals across the country to join the registry (a multicenter CBCR-IR). Currently, we are collaborating with 10 provinces (including 16 hospitals) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Centers Involved and Structure of Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

.

Centers Involved and Structure of Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

Establishment of the Minimum Dataset and the Software

During the pilot phase, a primary minimum dataset was developed using different international sources such as the International Classification of Diseases, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3),18 the 2016 Revision of Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards (FORDS),19 and the review of the international literature. The minimum dataset was further adjusted by a panel of experts including oncologists, surgeons, and epidemiologists. After the pilot phase of using the minimum dataset, it was updated and included some risk factors related to patient outcomes, comorbidities, and biopsy information. We also included both clinical and pathological staging of BC patients. The registry currently collects about 200 variables in different domains (Box 1). We adapted a web-based and open-source software called the District Health Information Software (DHIS2) for online data collection.20

Box 1. The minimum dataset of the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

Identifying information

Hospital name

Demographics (gender, nationality, etc.)

Contact details

Risk factors

Smoking, alcohol, opium, and hookah use

Menopause status and pregnancy at the time of diagnosis

History of breast cancer or other cancers

History of radiation on chest or neck

History of breast or ovarian cancer among the first- and second-degree relatives

Comorbidity

Cardiovascular diseases

Kidney and liver diseases

Chronic lung diseases

Cancers

Diabetes and overweigh

Brain and neurologic diseases

Biopsy and imaging information

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA), Core needle biopsy (CNB)

Mammography, sonography (breast, abdominal and pelvic), MRI (breast, brain), CT scan (chest wall, abdominal, and pelvic)

Staging (clinical - pathologic) and prognostic factors

Cancer identification

Tumor information

Lymph node information

Immunohistochemical factors

Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR), Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), Ki67, P53

Treatment

Surgery

Chemotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant)

Radiotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant)

Hormonotherapy

Targeted therapy

Follow-up

Vital status

Cause of death

Presence of local recurrence or distant metastasis

Type of record dates

Date of birth

Date of diagnosis

Date of biopsy sampling and imaging processes

Date of treatments

Date of last contact

Date of death

Date of local recurrence or distant metastasis

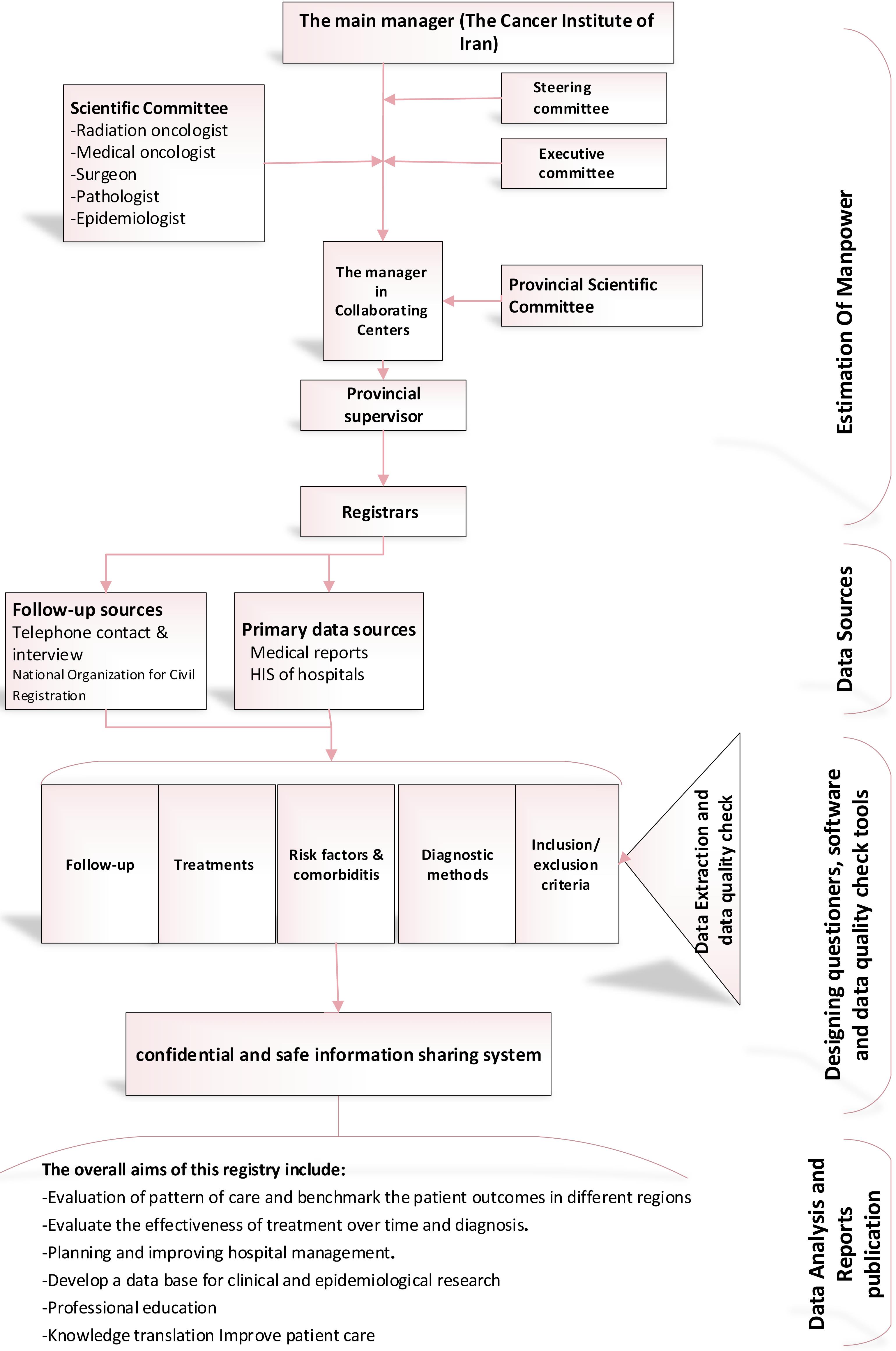

Structure and Organization

So far, 16 hospitals from 12 provinces across the country have been collaborating in the CBCR-IR network (Figure 1). The Cancer Institute of Iran is hosting and coordinating the registry network. In each collaborating center, a co-principal investigator (Co-PI) supervises a registry team to collect and monitor the quality of data of the registry in collaboration with the Cancer Institute (Figure 2). The recruitment of new centers is an ongoing process, and the number of centers is increasing. The processes for recruitment include evaluation of the readiness of a center, performing a pilot study and signing a collaboration agreement with the registry, and participation in a training session. Representatives from the participating centers are the members of the steering committee of CBCR-IR which act as the governing body for the registry.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of Patient Identification and Data Collection for the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

.

Flowchart of Patient Identification and Data Collection for the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

Selection of Hospitals or Centers/Provinces

The process of province selection includes five steps, namely: 1) sending a call for collaborating centers; 2) completing application and feasibility forms by the volunteering centers; 3) implementation of pilot phases in volunteer centers; 4) reviewing the results obtained by the Cancer Institute of Iran, selecting eligible centers; 5) signing an agreement between the main center and collaborating centers.

Each collaborating center establishes its organizational structure similar to the structure of the main center except on a smaller scale.

Education and Training

Two types of training courses were held, including in-person workshops at the beginning of activities in each center and periodic online workshop. In addition, a forum supports the registrars across the country and provides answers and explanations for the problems faced during the routine work.

Data Collection Process

The primary product of the cancer registry is reliable data on cancer cases. Various programs and major decisions are based on these data. Therefore, selecting the most appropriate method for data collection and determining the structure for quality control of data is critical for a cancer registry. It is imperative to note that a clinical cancer registry is structured by collecting data from different hospitals and health centers with an expansive range of differences in geographical location, access to diagnostic equipment, specialist resources, and financial constraints. As part of our clinical cancer registry, 12 provinces and 16 hospitals and health centers were included. These centers varied in terms of the number of patients treated as well as other parameters. Thus, the design and implementation of the project required a variety of management programs and flexibility to coordinate different departments.

The essential source of BC registry data items is medical reports (both inpatient and outpatient). Other sources for data collection were also used, including hospital information systems, and pathology and imaging reports. The centers contact patients and collect materials and information from patients or their next of kin. We also collect documents and follow-up information from the National Organization for Civil Registration, and actively through telephone interviews with patients or their caregivers.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We set the commencing date of the registry on January 1, 2014, and BC patients’ data was registered if their diagnosis was made after this date. The starting date of the registry for collaborating centers varied across different centers based on availability of the data. Each center recruited its patients if they had a diagnosis of BC and received one of their initial treatment procedures in that specific hospital. BC morphologies other than adenocarcinoma such as melanomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas were excluded from the CBCR-IR.

Limitation and Implementation Challenges

Our cancer registries had several limitations in terms of data collection and accuracy that needed to be addressed. These included 1) lack of access to old patient records, particularly those from the past few years, 2) lack of a specific and regulated structure for collecting diagnostic and therapeutic data on patients referred to medical centers by medical staff, 3) absence of electronic record systems, 4) illegibility of patients’ paper-based history records, 5) lack of access to patients for follow-up due to incorrect contact information, death or change in residence or unwillingness to cooperate because of dissatisfaction with the medical services provided, 6) lack of sufficient registrar training, 7) the need to update the registration guide and to hold continuous training sessions on how to access the right resources and gather quality information (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data Source Used by Different Centers for Collection of Patient Data in the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

|

Center Name

|

Medical Report

|

Telephone Contact

|

In-person Interview

|

Link with Other Centers or Provinces for Data Collection

|

| Tehran (Cancer Institute of Iran) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

| Urmia (Imam Khomeini Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Bushehr (The Persian Gulf Martyrs Hospital) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

| Arak (Ayatollah Khansari Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Kermanshah (Imam Reza Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Rasht (Poursina Hospital) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

| Mazandaran (Babol) (Ayatollah Rohani Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Isfahan (Omid& Alzahra Hospital) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

| Ilam (Mostafa Khomeini Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Sabzevar (Vaseei Hospital) |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Lorestan (Shahid Rahimi Hospital) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Sistan and Baluchestan (Zahedan) (Ali Ibn Ali

Taleb & Khatam al-Anbia Hospitals) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Quality Control Process

In terms of completeness and validity, our quality control team (including an oncologist expert and epidemiologist at the cancer institute) uses several methods to validate our registry data through: 1) reviewing 10 percent of randomly selected data from each year’s registered cases by trained registrars and providing feedback to the principal investigators (PIs) and registrars in each study site and 2) cross-validating with other sources of data, e.g. by contacting patients or their caregivers and/or using data from other databases (e.g. causes of death registry, operation lists, etc) in order to complete the missing information and continuously monitor data validity. Centers are allowed, if necessary, to interview patients face-to-face and collect missing data items.

Ethical Considerations and Privacy Issues with Secondary use of Data

We obtained ethics approval from Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) (Ethical Code: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.1015). Access to the data processing software is role-based and limited to people who are introduced by the manager of each center. Registrars and managers access the registry system using safe passwords.

The CBCR-IR’s online web-tool has various role-based access levels managed by the director at the Cancer Institute of Iran; for example, registrars can only import and edit data but cannot delete or export data. Moreover, each supervisor in different centers can export their own data and cannot access other centers’ data.

Furthermore, registrars and all team members have been trained to preserve the confidentiality of patient data and consider the ethical principles of this registry. In addition, we have developed a data sharing guideline and defined the roles and responsibilities for the registry teams and investigators requesting the data. Data are anonymized before sharing with researchers. All patient information is periodically backed up by the main center and the software server is protected by the Tehran University of Medical Science.

Results

From a total of 13 086 cases who were admitted to our network’s hospitals between January 1, 2014 to January 1, 2022, 7874 eligible BC patients were included in our analysis. The patients’ mean age at the time of diagnosis was 49 ± 13.60 years. Only 271 (3.44%) cases had a screening mammography (Table 2). The diagnostic methods were core needle biopsy from the tumor (61.25%) and diagnostic mammography (68.78%).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Methods of Breast Cancer Currently Included in the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

|

|

Province, No. (%)

|

|

Total

|

Center

1: Tehran*

|

Center

2: Urmia***

|

Center

3:Bushehr*

|

Center

4: Arak***

|

Center

5: Kermanshah***

|

Center

6: Rasht**

|

Center 7: Babol

|

Center 8:

Isfahan*

|

Center

9: Ilam***

|

Center

10:Sabzevar***

|

Center 11:

Lorestan*

|

Center

12: Zahedan*

|

| Overall |

7874 |

3244 41.20% |

396

5.03% |

225

2.86% |

266 3.38% |

309

3.92% |

411 5.22% |

198 2.51% |

2390 30.35% |

48 0.61% |

101

1.28% |

159 2.02% |

127 1.61% |

| Diagnostic methods |

Mammography (screening) |

271

3.44% |

99

3.05% |

10

2.53% |

8

3.56% |

15

5.64% |

0 |

3

0.73% |

2

1.01% |

121

5.06% |

2

4.17% |

2

1.98% |

9

5.66% |

0 |

| Mammography (diagnostic) |

5416 68.78% |

2444

75.34% |

109

27.53% |

189

84% |

119

44.74% |

85

27.51% |

280

68.13% |

31

15.66% |

1947

81.46% |

5

10.42% |

17

16.83% |

127

79.87% |

63

49.61% |

| Breast MRI |

1297 16.47% |

870

26.82% |

5

1.26% |

6

2.67% |

3

1.13% |

7

2.27% |

177

43.07% |

0 |

180

7.53% |

1

2.08% |

2

1.98% |

8

5.03% |

38

29.92% |

| Core needle biopsy (tumor) |

4823 61.25% |

2249

69.33% |

101

25.51% |

95

42.22% |

73

27.44% |

48

15.53% |

9

2.19% |

84

42.42% |

1952

81.67% |

5

10.42% |

24

23.76% |

129

81.13% |

54

42.52% |

| FNA (lymph node) |

1224 15.54% |

801

24.69% |

6

1.52% |

11

4.89% |

6

2.26% |

55

17.80% |

228

55.47% |

7

3.54% |

72

3.01% |

5

10.42% |

1

0.99% |

10

6.29% |

22

17.32% |

| Open biopsy |

1188 15.09% |

501

15.44% |

174

43.94% |

54

24% |

1

0.38% |

121

39.16% |

104

25.30% |

139

70.20% |

21

0.88% |

0 |

7

6.93% |

16

10.06% |

50

39.37% |

Numbering centres according to the place in the map (Figure 1).

* Information was collected using medical reports and telephone or in-person interview with patients

** Information was collected using telephone interviews with patients without access to medical reports

*** Information was collected using medical reports

Stage distribution was 2.03% carcinoma in situ, 12% stage I, 44.65% stage II, 21.32% stage III, and 4.61% stage IV; stage information was missing in 1532 patients (19.46%) (Table 3). On the basis of immunohistochemical information, 4409 (55.99%) of patients were estrogen receptors/ progesterone receptor (ER/PR) positive and 1725 (21.91%) were human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2) positive. However, the ER/PR and HER2 status were missing in 24.55% and 25.22%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Basic Characteristics of Breast Cancer Patients Currently Included in the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR. Iran (CBCR-IR)

|

|

Province, N (%)

|

|

Total

|

Center

1: Tehran*

|

Center

2: Urmia***

|

Center

3:

Bushehr*

|

Center

4: Arak***

|

Center

5: Kermanshah***

|

Center

6: Rasht**

|

Center 7: Babol

|

Center 8:

Isfahan*

|

Center

9: Ilam***

|

Center

10:

Sabzevar***

|

Center 11:

Lorestan*

|

Center

12: Zahedan*

|

| Overall |

7874 |

3244 41.20% |

396

5.03% |

225

2.86% |

266 3.38% |

309

3.92% |

411 5.22% |

198 2.51% |

2390 30.35% |

48 0.61% |

101

1.28% |

159

2.02% |

127 1.61% |

Staging at diagnosis

(clinical /pathologic) |

0 |

160

2.03% |

124

3.82% |

7

1.77% |

0 |

1

0.38% |

0 |

1

0.24% |

0 |

15

0.63% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| I |

939

11.93% |

395

12.18% |

33

8.33% |

42

18.67% |

26

9.77% |

24

7.77% |

0 |

23

11.62% |

358

14.98% |

4

8.33% |

10

9.90% |

35

22.02% |

1

0.79% |

| II |

3201 40.65% |

1386

42.73% |

120

30.30% |

86

38.22% |

144

54.14% |

75

24.27% |

6

1.46% |

81

40.91% |

1,160

48.54% |

11

22.92% |

49

48.51% |

75

47.17% |

8

6.30% |

| III |

1,679 2132% |

650

20.04% |

152

38.38% |

49

21.78% |

59

22.18% |

56

18.12% |

1

0.24% |

49

24.75% |

569

23.81% |

9

18.75% |

29

28.71% |

39

24.53% |

17

13.39% |

| IV |

363

4.61% |

154

4.75% |

16

4.04% |

10

4.44% |

8

3.01% |

42

13.59% |

0 |

9

4.55% |

89

3.72% |

1

2.08% |

8

7.92% |

10

6.29% |

16

12.60% |

| Unknown |

1532 19.46% |

535

16.49% |

68

17.17% |

38

16.89% |

28

10.53% |

112

36.25% |

403

98.05% |

36

18.18% |

199

8.33% |

23

47.92% |

5

4.95% |

0 |

85

66.93% |

| ER /PR receptor |

Positive |

4409 5599% |

1866

57.52% |

130

32.83% |

150

66.67% |

162

60.90% |

143

46.28% |

8

1.95% |

98

49.49% |

1,641

68.66% |

10

20.83% |

64

63.37% |

110

69.18% |

27

21.26% |

| Negative |

1532 19.46% |

601

18.53% |

53

13.38% |

53

23.56% |

56

21.05% |

48

15.53% |

1

0.24% |

21

10.61% |

612

25.61% |

7

14.58% |

27

26.73% |

37

23.27% |

16

12.60% |

| Unknown |

1933 24.55% |

777

23.95% |

213

53.79% |

22

9.78% |

48

18.05% |

118

38.19% |

402

97.81% |

79

39.90% |

137

5.73% |

31

64.58% |

10

9.90% |

12

7.55% |

84

66.14% |

| HER2 receptor |

Positive |

1725 21.91% |

687

21.18% |

59

14.90% |

70

31.11% |

44

16.54% |

124

40.13% |

2

0.49% |

31

15.66% |

597

24.98% |

12

25% |

21

20.79% |

51

32.08% |

27

21.26% |

| Negative |

3661 46.49% |

1490

45.93% |

109

27.53% |

112

49.78% |

146

54.89% |

65

21.04% |

7

1.70% |

83

41.92% |

1,492

62.43% |

7

14.58% |

61

60.40% |

70

44.03% |

19

14.96% |

| borderline |

502

6.38% |

261

8.05% |

10

2.53% |

23

10.22% |

28

10.53% |

1

0.32% |

0 |

6

3.03% |

146

6.11% |

0 |

6

5.94% |

21

30.21% |

0 |

| Unknown |

1986 25.22% |

806

24.85% |

218

55.05% |

20

8.89% |

48

18.05% |

119

38.51% |

402

97.81% |

78

39.39% |

155

6.49% |

29

60.42% |

13

12.87% |

17

10.69% |

81

63.78% |

Centre numbering according to the location in the map (Figure 1).

* Information was collected using medical reports and telephone or in-person interviews with patients.

** Information was collected using telephone interviews with patients without access to medical reports.

*** Information was collected using medical reports.

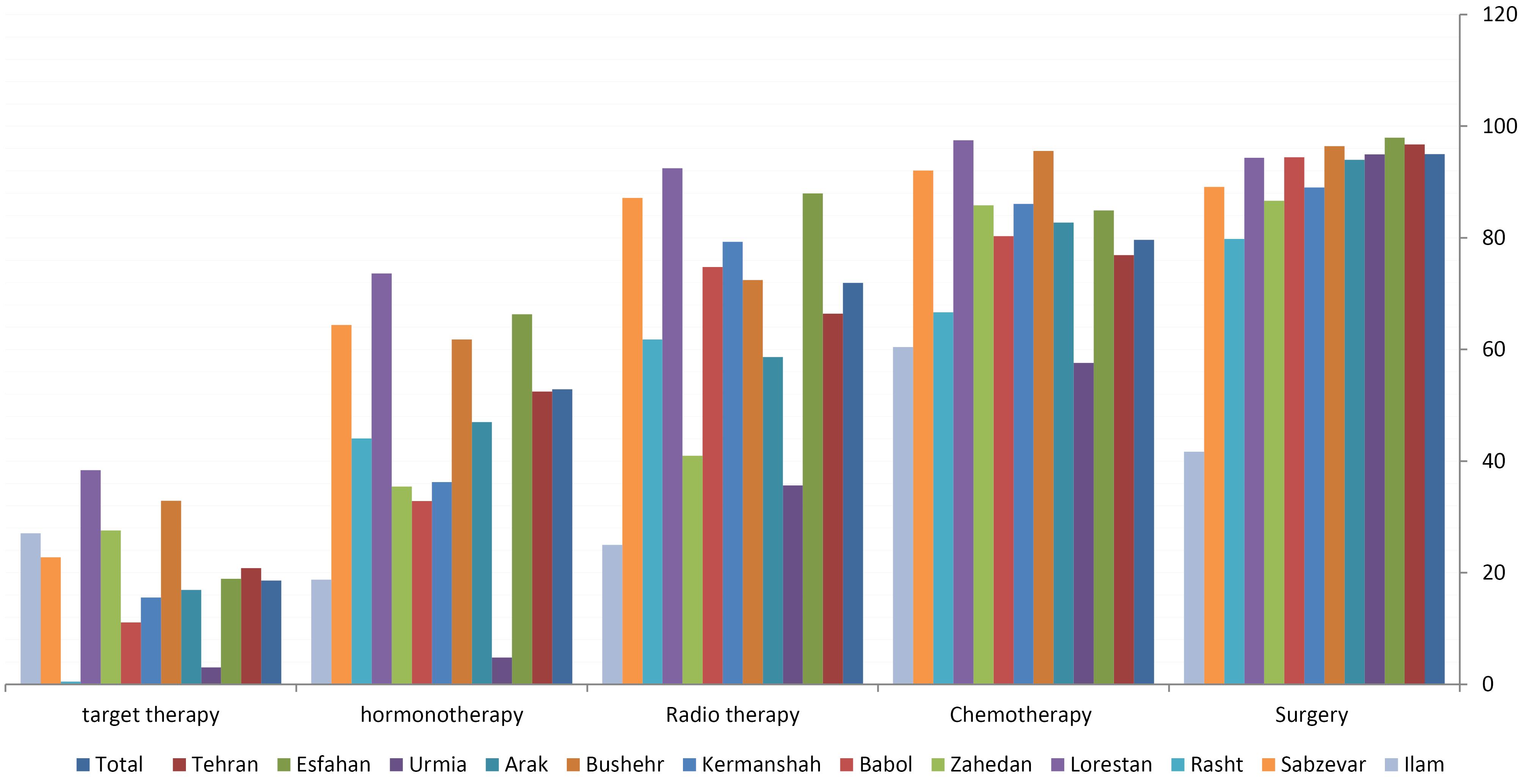

Surgery (95.01%) and chemotherapy (79.65%) were the most common treatments for all patients (Figure 3). Only about 17% of patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. We also found that 66.43% of patients received adjuvant radiotherapy. The proportion of hormone therapy and targeted therapy in our study population was 52.88% and 20.81%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Treatment Methods of Breast Cancer Patients Currently Included in the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR.Iran (CBCR-IR)

.

Treatment Methods of Breast Cancer Patients Currently Included in the Clinical Breast Cancer Registry of IR.Iran (CBCR-IR)

Discussion

This program provides a valuable database about BC patient care from different geographical areas in Iran. It includes more than 200 variables and collects high quality data about demographics, risk factors, diagnosis, treatments, and follow-ups. This registry has registered more than 8000 BC patients across the country and provides an opportunity to conduct several studies about BC care and to determine the status of the care indicators of BC care in Iran overall and by hospitals located in different parts of the country. The registry makes it possible to compare hospitals and monitor the improvement after interventions in the patient care in each participating center and the country overall. As a result, policy makers will receive ongoing feedback that will help reduce inequalities across hospitals, improve tailored treatments, and increase compliance with national guidelines.

Clinical performance and outcomes can be measured and tracked using quality indicators (QIs), which are standardized, evidence-based measures of quality of care. A list of 33 benchmark QIs was proposed by the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) in 2010 and updated in 2017 to allow standardized auditing and quality assurance of care.21 Clinical cancer registries as a source of information about steps of diagnosis and treatment can help to determine and publish QIs that are being used in a variety of medical studies, and they provide an ideal infrastructure for estimating QIs regularly and comparing IQs across hospitals that may facilitate changes in guidelines.22 For example, studies published recently have shown that women undergoing breast conserving therapy have a better survival rate than those undergoing mastectomy.21-27 Quality care assessment is common in developed nations but is very rare in developing countries. Recently, a study in Morocco reported the result of breast QIs in that country.28 Our registry provides access to large datasets from several hospitals, which can be used to evaluate the quality-of-care levels across Iran.

In addition to evaluating standards and guideline adherence, it is crucial to determine limitations and correct weaknesses in the diagnosis and treatment processes. One of the most critical sections relates to improving the infrastructure and access to essential cancer care services, which is expected to improve patient outcomes and reduce cancer incidence. A study showed that Eastern Mediterranean Regional (EMRO) countries, such as Iran, encounter varying conditions in terms of access to diagnostic equipment, such as computerized tomography (CT) scanners, magnetic resonance imagines (MRIs), and positron emission tomography (PET) scanners.29 In the EMRO region, our CBCR is the largest database, which can answer a wide range of questions regarding quality of care and access to health services. Also, governments with a focus on CBCR data can determine policy makers rules and monitor programs that would affect the GBCI.12,13 By analyzing the available data, we will be able to evaluate key strategies to achieve the objectives of GBCI, including health promotion and early detection, timely diagnosis, and comprehensive BC management.12,13

We encountered a number of challenges in our study. Since hospitals and facilities in different provinces have different management systems (Table 1), the primary registry protocol needed to be changed to accommodate the differences. There is missing data in some sections due to these variations across centers. For example, the completeness of staging data was 80.54% for BC in our study, which compares weakly with 94% of the Australian national average or 90% of Canada in 2010 for female BC.30,31 In order to overcome challenges, we had to employ a variety of management strategies, including in-person interviews, integrating data from other sources, and conducting telephone follow-ups.

In conclusion, the information provided by this registry can be used to evaluate and improve the quality of care for BC patients. It will be scaled up to the national level as an important resource for measuring quality of care and conducting clinical cancer research in Iran.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Cancer Research Centre, Cancer Institute (Tehran University of Medical Sciences), Clinical Research Development Center, The Persian Gulf Martyrs (Bushehr University of Medical Science), Imam Khomeini Hospital (Urmia University of Medical Sciences), Ayatollah Khansari Hospital (Arak University of Medical Sciences), Imam Reza Hospital (Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences), Poursina Hospital (Gilan University of Medical Sciences), Ayatollah Rohani Hospital(Babol University of Medical Sciences), Omid and Alzahra Hospital (Isfahan University of Medical Sciences), Mostafa Khomeini Hospital (Ilam University of Medical Sciences), Vaseei Hospital (Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences), Shahid Rahimi Hospital (Lorestan University of Medical Sciences), Ali Ibn Ali Taleb and Khatam al-Anbia Hospitals (Zahedan University of Medical Sciences) and other members of the cancer registry for their guidance and support.

Competing Interests

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

This article has ethical approval with approval ID: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.1015 and IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1400.231 evaluated by the vice-chancellor in research affairs, Tehran University of medical sciences.

Funding

We would also like to show our gratitude to the national clinical breast cancer registry and colleague’s provinces (Tehran, Urmia, Bushehr, Arak, Kermanshah, Rasht, Mazandaran, Isfahan, Lorestan, Sistan and Baluchestan) with grants number 99-01-115-46513 and 1400-01-115-52576 for sharing their clinical breast cancer data with us during the course of this research.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71(3):209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020; 70(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zendehdel K. Cancer statistics in IR Iran in 2018. Basic Clin Cancer Res 2019; 11(1):1-4. doi: 10.18502/bccr.v11i1.1645 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rafiemanesh H, Salehiniya H, Lotfi Z. Breast cancer in Iranian woman: incidence by age group, morphology and trends. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016; 17(3):1393-7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.3.1393 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Asadzadeh Vostakolaei F, Broeders MJ, Mousavi SM, Kiemeney LA, Verbeek AL. The effect of demographic and lifestyle changes on the burden of breast cancer in Iranian women: a projection to 2030. Breast 2013; 22(3):277-81. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.07.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Daroudi R, Akbari Sari A, Nahvijou A, Kalaghchi B, Najafi M, Zendehdel K. The economic burden of breast cancer in Iran. Iran J Public Health 2015; 44(9):1225-33. [ Google Scholar]

- Sharifian A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Emadedin M, Rostami Nejad M, Ashtari S, Hajizadeh N. Burden of breast cancer in Iranian women is increasing. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16(12):5049-52. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.12.5049 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Francies FZ, Hull R, Khanyile R, Dlamini Z. Breast cancer in low-middle income countries: abnormality in splicing and lack of targeted treatment options. Am J Cancer Res 2020; 10(5):1568-91. [ Google Scholar]

- Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies-an updated review. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13(17):4287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174287 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Askarzade E, Adel A, Ebrahimipour H, Badiee Aval S, Pourahmadi E, Javan Biparva A. Epidemiology and cost of patients with cancer in Iran: 2018. Middle East J Cancer 2019; 10(4):362-71. doi: 10.30476/mejc.2019.83412.1162 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Anderson BO, Ilbawi AM, Fidarova E, Weiderpass E, Stevens L, Abdel-Wahab M. The Global Breast Cancer Initiative: a strategic collaboration to strengthen health care for non-communicable diseases. Lancet Oncol 2021; 22(5):578-81. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00071-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM. The role of cancer registries in cancer control. Int J Clin Oncol 2008; 13(2):102-11. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0762-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh Z, Ghazisaeedi M, Nahvijou A, Rostam Niakan Kalhori S, Davoodi S, Zendehdel K. Systematic review of hospital-based cancer registries (HBCRs): necessary tool to improve quality of care in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017; 18(8):2027-33. doi: 10.22034/apjcp.2017.18.8.2027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jensen OM, Parkin DM, MacLennan R, Muir CS, Skeet RG. Cancer Registration: Principles and Methods. IARC Scientific Publication No. 95. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 1991.

- Ruiz A, Facio Á. Hospital-based cancer registry: a tool for patient care, management and quality A focus on its use for quality assessment. Rev Oncol 2004; 6(2):104-13. doi: 10.1007/bf02710038 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rouhollahi M, Mohagheghi MA, Mohammadrezai N, Ghiasvand R, Ghanbari Motlagh A, Harirchi I. Situation analysis of the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (2013) in the IR of Iran; assessment and recommendations based on the IAEA imPACT mission. Arch Iran Med 2014; 17(4):222-31. [ Google Scholar]

- Seyyedsalehi MS, Nahvijou A, Rouhollahi M, Teymouri F, Mirjomehri L, Zendehdel K. Clinical cancer registry of the Islamic Republic of Iran: steps for establishment and results of the pilot phase. J Registry Manag 2020; 47(4):200-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, et al. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2000.

- American College of Surgeons (ACS). Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards (FORDS): Revised for 2015. ACS; 2015.

- Dehnavieh R, Haghdoost A, Khosravi A, Hoseinabadi F, Rahimi H, Poursheikhali A. The District Health Information System (DHIS2): a literature review and meta-synthesis of its strengths and operational challenges based on the experiences of 11 countries. Health Inf Manag 2019; 48(2):62-75. doi: 10.1177/1833358318777713 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Del Turco MR, Ponti A, Bick U, Biganzoli L, Cserni G, Cutuli B. Quality indicators in breast cancer care. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46(13):2344-56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.119 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adami HO, Hernán MA. Learning how to improve healthcare delivery: the Swedish Quality Registers. J Intern Med 2015; 277(1):87-9. doi: 10.1111/joim.12315 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hwang ES, Lichtensztajn DY, Gomez SL, Fowble B, Clarke CA. Survival after lumpectomy and mastectomy for early-stage invasive breast cancer: the effect of age and hormone receptor status. Cancer 2013; 119(7):1402-11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27795 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, Kokeny K, Agarwal J. Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg 2014; 149(3):267-74. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3049 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Johnsen OJ, Kåresen R, Schlichting E, Nygård JF. Survival is better after breast conserving therapy than mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer: a registry-based follow-up study of Norwegian women primary operated between 1998 and 2008. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22(12):3836-45. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4441-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Liu J, Zhu L, Su F, Song E, Jacobs LK. Comparative effectiveness study of breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy in the general population: a NCDB analysis. Oncotarget 2015; 6(37):40127-40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5394 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Christiansen P, Carstensen SL, Ejlertsen B, Kroman N, Offersen B, Bodilsen A. Breast conserving surgery versus mastectomy: overall and relative survival-a population-based study by the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Acta Oncol 2018; 57(1):19-25. doi: 10.1080/0284186x.2017.1403042 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- 28 Mrabti H, Sauvaget C, Benider A, Bendahhou K, Selmouni F, Muwonge R. Patterns of care of breast cancer patients in Morocco - a study of variations in patient profile, tumour characteristics and standard of care over a decade. Breast 2021; 59:193-202. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.07.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vand Rajabpour M, Camacho R, Fadhil I, Al-Bahrani BJ, Elberri HH, El Saghir NS, et al. Access to Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. In: Cancer Control: Eastern Mediterranean Region Special Report; 2022. p. 55-67.

- Cancer Australia. National Cancer Stage at Diagnosis Data. 2018. Available from: https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/features/national-cancer-stage-diagnosis-data.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Canada Reports First-Ever Cancer Stage Data. 2015. Available from: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/news-events/news/article/canada-reports-first-ever-cancer-stage-data/.