Arch Iran Med. 26(2):110-116.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.17

Original Article

Prevalence of Chromosomal Abnormalities in Iranian Patients with Infertility

Saima Abbaspour Conceptualization, Visualization, 1, #

Alireza Isazadeh Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 2, #

Matin Heidari Project administration, Writing – original draft, 3

Masoud Heidari Methodology, Visualization, 4

Saba Hajazimian Formal analysis, Project administration, 2

Morteza Soleyman-Nejad Data curation, Methodology, 3

Mohammad Hossein Taskhiri Data curation, 3

Manzar Bolhassani Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 3

Amir Hossein Ebrahimi Data curation, Writing – original draft, 3

Parvaneh Keshavarz Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, 1

Zahra Shiri Methodology, 3

Mansour Heidari Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 3, 5, *

Author information:

1Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2Immunology Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Ariagene Medical Genetics Laboratory, Qom, Iran

4Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

5Department of Medical Genetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Tehran, Iran

#Contributed equally to the work as first authors.

Abstract

Background:

The numerical and structural abnormalities of chromosomes are the most common cause of infertility. Here, we evaluated the prevalence and types of chromosomal abnormalities in Iranian infertile patients.

Methods:

We enrolled 1750 couples of reproductive age with infertility, who referred to infertility clinics in Tehran during 2014- 2019, in order to perform chromosomal analysis. Peripheral blood samples were obtained from all couples and chromosomal abnormalities were evaluated by G-banded metaphase karyotyping. In some cases, the detected abnormalities were confirmed using fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH).

Results:

We detected various chromosomal abnormalities in 114/3500 (3.257%) patients with infertility. The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities was 44/114 (38.596%) among infertile females and 70/114 (61.403%) among infertile males. Structural chromosomal abnormalities were found in 27/1750 infertile females and 35/1750 infertile males. Numerical chromosomal abnormalities were found in 17/1750 of females and 35/1750 of males. The 45, XY, rob (13;14) (p10q10) translocation and Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY) were the most common structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities in the Iranian infertile patients, respectively.

Conclusion:

In general, we found a high prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in Iranian patients with reproductive problems. Our study highlights the importance of cytogenetic studies in infertile patients before starting infertility treatments approaches.

Keywords: Chromosomal abnormalities, Cytogenetics, Infertility, Karyotyping

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Abbaspour S, Isazadeh A, Heidari M, Heidari M, Hajazimian S, Soleyman Nejad M, et al. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in iranian patients with infertility. Arch Iran Med. 2023;26(2):110-116. doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.17

Introduction

Infertility is described as the incapacity to conceive naturally after one year of unprotected sexual intercourse.1 This condition is one of the common health problems and involves large number of couples worldwide. The epidemiological data demonstrates that 15.0% of the Iranian population are unable to conceive naturally during the first year of marriage.2 Most infertile couples will conceive spontaneously after the first year or respond to treatment, so that only 5.0% of the population remain unable to conceive.3 Various factors including genetics, infections, endocrine issues, lifestyle, and environment are involved in the infertility of males and females.4-8

Chromosomal abnormalities are the most common causes of genetic defects, and are known as an important cause of reproductive problems, spontaneous abortion, and fetal death.8 Various chromosomal variants and major chromosomal abnormalities have been found in 1.3-15.0% of couples with reproductive problems.9,10 The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in infertile males is 1.1-7.2%,11,12 whereas in infertile females, it is 10.0%.13,14 Structural rearrangements (inversions) and sex chromosomal mosaicism are reported as the most frequent chromosomal abnormalities in individuals with reproductive problems.15 Moreover, balanced and reciprocal translocations are common structural rearrangements in populations with infertility.16

Due to the high prevalence and remarkable effects of chromosomal abnormalities in human infertility, the aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in an Iranian population with reproductive problems.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

In the present study, we enrolled 1750 couples with infertility (1750 women and 1750 men), who referred to infertility clinics (Tehran, Iran) from January 2014 until January 2019. Patients with diagnosed causes of infertility, other than chromosomal abnormalities, were excluded from our study. Genetic counselling of the studied infertile patients included inheritance risk of chromosomal abnormalities, spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies, and fetal death. All patients were informed about the study and an informed consent was signed according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was performed with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Chromosome Analysis

Peripheral blood samples (5 mL) of the studied patients were collected and added to a heparinized tube. Blood sample culture was performed using the RPMI-1640 culture medium containing fetal bovine serum (FBS), phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), and penicillin-streptomycin (Pen/Str). Cytogenetic analysis was conducted on Giemsa-Trypsin-Giemsa (GTG)-banded metaphase chromosomes with banding resolution of 450-550 bands per patients. Various chromosomal polymorphisms, such as pericentric inversion in the short arm of chromosome 9, were considered normal variants. In the mosaicism cases, 50–100 additional metaphases were analyzed to detect the percentage of mosaicism. The chromosomal abnormalities were observed and detected using computerized Karyotyper (Cytovision 2.7). In addition, fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) with designed probes was performed to assess the level of mosaicism or confirm the type of abnormality in 198 cases (25). The analyzed karyotype was reported according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.

Results

Clinical Information of Patients

In the present study, we enrolled 1750 infertile couples (31 ± 1.8 years old). The demographic characteristics and general features of the infertile patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and General Features of Patients with Infertility

|

Characteristic

|

Women (n=1750)

|

Men (n=1750)

|

| Age (y) |

27.18 ± 2.76 |

35.84 ± 1.19 |

| Duration of infertility (y) |

5.56 ± 2.24 |

4.78 ± 2.81 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

25.56 ± 3.53 |

23.15 ± 2.25 |

| Age at menarche (year) |

13.11 ± 1.22 |

- |

| Tobacco smoking (%) |

114 (6.51%) |

611 (34.91%) |

| Alcohol drinking (%) |

86 (4.91%) |

501 (28.62%) |

| Genetic background (%) |

41 (2.34%) |

38 (2.17%) |

Normal Chromosomal Variants

The karyotypes of 59 (1.685%) all infertile patients were found with normal chromosomal variants, including inv(9)(p11q13), 13pstk, 14pstk, 15pstk, 22pstk. We also observed other rare normal variants in the infertile patients, including enlarged heterochromatin of the chromosome 9q and reduced length of heterochromatin in chromosome Y. The normal chromosomal variants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Normal Chromosomal Variants Observed in 3500 Patients with Infertility

|

Normal Variants

|

Females (n=1750)

|

Males (n=1750)

|

Total (n=3500)

|

| 13pstk |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.057%) |

2 (0.057%) |

| 14pstk |

2 (0.114%) |

1 (0.057%) |

3 (0.085%) |

| 15pstk |

11 (0.628%) |

13 (0.742%) |

24 (0.685%) |

| 22pstk |

1 (0.057%) |

3 (0.171%) |

4 (0.114%) |

| inv(9)(p11q13) |

9 (0.171%) |

7 (0.400%) |

16 (0.457%) |

| Enlarged 9q |

2 (0.114%) |

— |

2 (0.057%) |

| Reduced Yq |

— |

8 (0.457%) |

8 (0.228%) |

|

Total

|

26 (1.485%) |

33 (1.885%) |

59 (1.685%) |

Total Chromosomal Abnormalities

The abnormal karyotype was observed in 3.257% (114 cases) of patients with infertility. The prevalence of abnormal karyotype in infertile males was 61.403% (70 cases), whereas it was 38.596% (44 cases) in infertile females. The prevalence of structural chromosomal abnormalities (62/3500) was more than the prevalence of numerical chromosomal abnormalities (52/3500) in all patients. We observed only one case with Y microdeletion, 46, XY, del(Y)(q11.2), and one case with deletion in the AZFc region. All structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities detected in infertile patients are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities Observed in 3500 Patients with Infertility

|

Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities

|

Karyotype

|

Males (n=1750)

|

Females (n=1750)

|

Total (n=3500)

|

| Duplications |

46, XX, dup(18)(p11;32) |

- |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| Ring chromosome |

46, XX, r[18](p11q22) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| Deletions |

46, XY, del(Y)(q11.2) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, del(18)(q22) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| Inversion |

46, XY, inv(4)(p13q13) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, inv(2)(p24q12) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, inv(6)(p21.2q22) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, inv(7)(p15.1q22) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(7)(p31.1q33) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(9)(p11q13) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, inv(1)(q13p31) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(1)(q23p13) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(8)(p22q13) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, inv(9)(p11q12) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(9)(p11q12) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(9)(p12q13) |

— |

3 (0.171%) |

3 (0.085%) |

| 46, XY, inv(9)(p12q13) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, inv(9)(p13q34) |

— |

2 (0.114%) |

2 (0.057%) |

| 46,XY,inv(9)(p13q34) |

4 (0.228%) |

— |

4 (0.114%) |

| Translocations |

45, XY, rob(14;21)(p10q10) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, XX, rob(13;14)(p10q10) |

— |

2 (0.114%) |

2 (0.057%) |

| 45, XY, rob(13;14)(p10q10) |

7 (0.400%) |

— |

7 (0.200%) |

| 46, XY, t(1;13)(p32.2q34) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(1;12)(p32.2q15) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(2;8)(p37.2q11) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(9;15)(p21q15) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(13;14)(p21.1q32.3) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(17;22)(p21.3q13.3) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(1;19)(p13q13.3) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(9;3)(q32q28) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(2;18)(q36q24) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(4;13)(p11q11) |

— |

4 (0.228%) |

4 (0.114%) |

| 46, XX, t(1,14)(p22q22) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(11;13)(p21q32) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, XY, t(11;22)(q23q11) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, XY, der(13;14)(q10q10) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(3;7)(p27p21) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(4;16)(q12p13) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(1;16)(p11p11) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(10;14)(q12q22) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(3;9)(p13q24) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(6;19)(q16q13) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, XY, t(6;20)(p27q11.2) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(1;13)(q22q14) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(3;4)(q12p15) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XX, t(3;4)(q13q21) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| Total |

35 (2.000%) |

27 (1.542%) |

62 (1.771%) |

Table 4.

Numerical Chromosomal Abnormalities Observed in 3500 Patients with Infertility

|

Numerical Chromosomal Abnormalities

|

Karyotype

|

Males (n=1750)

|

Females (n=1750)

|

Total (n=3500)

|

| Turner syndrome |

45, X |

— |

7 (0.400%) |

7 (0.200%) |

| Klinefelter syndrome |

47, XXY |

26 (1.485%) |

— |

26 (0.742%) |

| 47, XYY syndrome |

47, XYY |

6 (0.342%) |

— |

6 (0.171%) |

| 47, XXX syndrome |

47, XXX |

— |

4 (0.228%) |

4 (0.114%) |

| Mosaicism |

45, X, [4]/46, XX[92]/47, XXX [4] |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, X [6]/47, XXX [24], Turner |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, X [3]/46, X, i(X)(q10)[17], Turner |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, X, [2]/46, XX, [63] |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 45, X [7]/46, XX [43] |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| 47, XY + mar [35]/46, XY [65] |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, XY, t(1;2)(p11.1q11.1)[15]/46, XY [85] |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| Isochromosome |

46, XY, i(20)(q10) |

1 (0.057%) |

— |

1 (0.028%) |

| 46, X, i(X)(q10) |

— |

1 (0.057%) |

1 (0.028%) |

| Total |

35 (2.000%) |

17 (0.971%) |

52 (1.485%) |

Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities

Translocations:Translocations are the most frequent type of structural chromosomal abnormalities, which were observed in 1.057% (21 males and 16 females) of patients with infertility. These abnormalities were detected in 32.456% of the all chromosomal abnormalities. Moreover, Robertsonian translocation was detected in 10 cases (8 males and 2 females).

Inversions: Inversions are the second most frequent structural chromosomal abnormalities, which were observed in 0.600% (11 males and 10 females) of patients with infertility. These abnormalities constituted 18.421% of all chromosomal abnormalities. All detected inversions were pericentric (21 cases), and we did not find any paracentric inversions.

Deletions: Deletions were found in 0.057% (2 males) of patients with infertility, which constituted 1.754% of all chromosomal abnormalities. The observed deletions occurred in the chromosomes 18 and Y of 2 males with infertility.

Duplications: Duplications were detected in 0.028% (one female) of patients with infertility, which constituted 0.877% of all detected chromosomal abnormalities. The observed duplication was found in the chromosome 18 of one female with infertility.

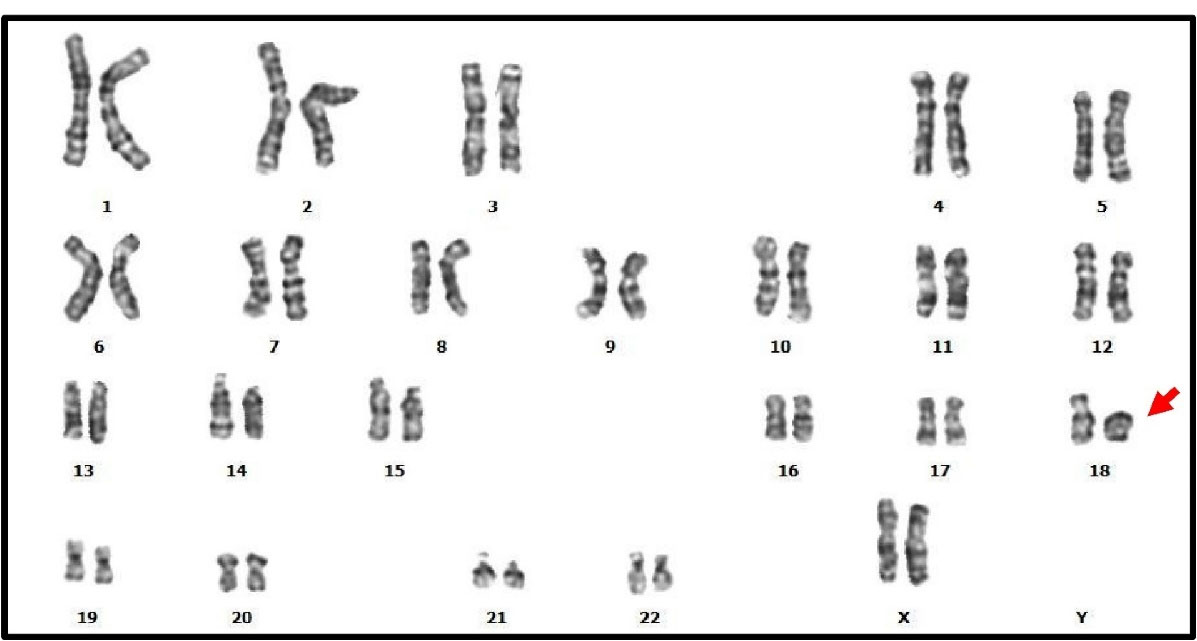

Ring chromosome:Ring chromosomes were observed in 0.028% (one female), which constituted 0.877% of all chromosomal abnormalities. The observed ring chromosome 18 was detected in one female with infertility (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Karyotype by Giemsa Banding of a Infertile Female with Infertility. We found a ring chromosomes: 46, XX, r[18](p11q22).

.

The Karyotype by Giemsa Banding of a Infertile Female with Infertility. We found a ring chromosomes: 46, XX, r[18](p11q22).

Numerical Chromosomal Abnormalities

Klinefelter syndrome:The Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY) is the most frequent type of numerical chromosomal abnormality, which was observed in 0.742% (26 males) of patients with infertility. This abnormality constituted 22.807% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 50% of numerical chromosomal abnormalities.

Turner syndrome: The Turner syndrome (45, X) is the second most frequent numerical chromosomal abnormality, which was observed in 0.200 (7 females) of patients with infertility. This abnormality constituted 6.140% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 13.461% of all numerical chromosomal abnormalities.

47, XYY syndrome:The 47, XYY syndrome was detected in 0.171% (6 males) of patients with infertility. This abnormality constituted 3.263% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 11.538% of numerical chromosomal abnormalities.

47, XXX syndrome:The 47, XXX syndrome was detected in 0.114% (4 females) of patients with infertility. This abnormality constituted 5.508% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 7.692% of numerical chromosomal abnormalities.

Isochromosome:Isochromosomes were detected in 0.057% (one male and one female). This abnormality constituted 1.754% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 3.846% of numerical chromosomal abnormalities. The isochromosome of chromosome 20 was observed in one male and the isochromosome of chromosome X was observed in one female.

Mosaicism:Mosaicism was detected in 0.20% (2 males and 5 females). This abnormality constituted 5.263% of all chromosomal abnormalities, and 11.538% of numerical chromosomal abnormalities.

Sex Chromosome Abnormalities

Sex chromosomal abnormalities were detected in 49 cases (42.982% of all chromosome abnormalities), consisting of 33 males (66.000%) and 17 females (34.000%). Aneuploidy of the X chromosome was observed in 43 patients, which included 11 females with karyotype 45, X and 47, XXX as well as 32 males with karyotype 47, XXY and 47, XYY. Moreover, sex chromosome mosaicism was observed in 5 females. Structural Y chromosome abnormality (deletion) was detected in one male with infertility (Tables 3 and 4).

Autosomal Chromosomes Abnormalities

Autosomal chromosomal abnormalities were detected in 64 cases (56.140% of all chromosome abnormalities), consisting of 37 males (57.812%) and 27 females (42.187%). The observed autosomal abnormalities included inversion, translocations (reciprocal and Robertsonian), isochromosome, and ring chromosome (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

Infertility is a troubling and destructive event in young couples, which can be remedied by current approaches in a high proportion of patients. However, identification of the etiology is an important consideration for appropriate and effective treatment strategies. The genetical and chromosomal abnormalities are the most important and frequent risk factors in patients with infertility.10,11 The high prevalence of various chromosomal abnormalities suggests that the chromosomal analysis of couples can be useful in reproduction management and healthy pregnancy.12 Chromosomal analysis or karyotyping is an appropriate diagnostic approach that provides important genetic information from couples. Identification of chromosomal breakpoint regions is important for recognition of genes involved in molecular mechanisms underlying human reproduction, and helping with the management of pregnancy.

The present study was designed to identify chromosomal abnormalities in Iranian men and women with infertility. We demonstrated that the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in Iranian infertile patients was 3.257% (61.403% in males and 38.596% in females) which is similar to other studies in different countries.17,18 In a study by Clementini et al, chromosomal abnormalities were observed in 82 cases (3.95%) out of 2078 patients with infertility.18 In another study by Pylyp et al, chromosomal abnormalities were reported in 81 cases (2.79%) out of 3414 patients with infertility.14 In addition, the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in patients with infertility ranged from 1% by Liang et al in China to 6% by Gekas et al. in France.19,20 Furthermore, several other studies have reported the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in couples with infertility in the worldwide. The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in infertile patients depends largely on characteristics of the studied population (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence of Chromosomal Abnormalities in Couples with Infertility in Different Studies

|

Authors

|

Year

|

Region

|

Sample Size (n)

|

Chromosomal Abnormalities

|

|

Men

|

Women

|

Total

|

Men

|

Women

|

Total

|

| El-Dahtory et al9 |

2022 |

Egypt |

1290 |

860 |

2150 |

150 (11.62%) |

140 (16.27%) |

290 (13.48%) |

| Pashaei et al12 |

2021 |

Iran |

528 |

527 |

1055 |

19 (3.59%) |

15 (2.84%) |

34 (3.22%) |

| Pylyp et al14 |

2015 |

Ukraine |

1673 |

1741 |

3414 |

47 (2.80%) |

34 (1.95%) |

81 (2.37%) |

| Kayed et al15 |

2006 |

Egypt |

2650 |

2650 |

5300 |

138 (5.20%) |

24 (0.90%) |

162 (3.05%) |

| Serapinas et al16 |

2021 |

Lithuania |

99 |

99 |

198 |

4 (4.04%) |

9 (9.09%) |

13 (6.56%) |

| Clementini et al18 |

2005 |

Italy |

2078 |

2078 |

4156 |

42 (2.02%) |

40 (1.92%) |

82 (1.97%) |

In our study, the structural chromosomal abnormalities were more than numerical chromosomal abnormalities, constituting 54.38% of all chromosomal abnormalities in infertile patients. Among structural abnormalities, translocations were the most frequent rearrangement and were observed in 59.67% of all structural chromosomal abnormalities. All detected translocations in this study were familiar with the same breakage and reunion regions. However, a number of non-familial translocations with individual breakage and reunion regions in different families have been reported by previous studies.21,22 A high number of palindromic AT repeats in a chromosomal region is one of the important reasons of double-stranded DNA breaks that leads to formation of non-familial translocations through non-homologous ends binding.21 Inversions were the second most frequent type of chromosomal rearrangements in our study which were observed in 18.42% of infertile patients. The paracentric and pericentric inversions of chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 were detected in our study. The pericentric inversion of chromosome 9 was considered as a normal variant.23 However, evidence suggests that the prevalence of inversions in patients with infertility is higher than the general population.23,24

Production of unbalanced gametes is the most important cause of reproductive problems in carriers of structural chromosomal rearrangements. The prevalence of unbalanced sperm in carriers of Robertsonian and reciprocal translocations ranges from 9 to 29% and 37 to 81%, respectively. However, the prevalence of unbalanced sperm in carriers of inversion ranges from 0.2 to 38% that highly depends on the size of the inverted segment.25 Therefore, prenatal diagnosis is an essential approach to exclude fetuses with unbalanced karyotype in carriers of chromosomal abnormalities. In addition, preimplantation genetic diagnosis is an appropriate alternative approach to invasive prenatal diagnosis in couples where pregnancy termination is not possible.26 In this applied method, normal embryos with balanced karyotype are transferred to the uterus, thus increasing the probability of healthy pregnancy, and significantly decreasing the risk of miscarriage and livebirth of children with unbalanced chromosomal abnormality.27

In the present study, sex chromosome abnormalities comprised 42.98% of all chromosomal abnormalities in infertile patients, consisting of sex chromosomes aneuploidies (97.95%) and chromosome Y microdeletion (2.05%). Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY) comprised 53.06% of all sex chromosome abnormalities and was the most frequent type of sex chromosome abnormality. A study by Pylyp et alreported that Klinefelter syndrome comprised 57.89% of all sex chromosome abnormalities in patients with infertility in a Ukrainian population.14 Klinefelter syndrome was the most common chromosome abnormality in men with oligozoospermia and azoospermia. However, the prevalence of this aneuploidy is quite variable across different populations.18 The second chromosomal abnormality was chromosome Y microdeletion which was observed in only one infertile male. The mosaic karyotype of sex chromosomes comprised 4.38% of all chromosomal abnormalities in patients with infertility. Sex chromosome mosaicism is normally observed in men with severe oligozoospermia.28

The prevalence of sex chromosome aneuploidies in men was higher than women. In this study, we detected four women with X chromosome trisomy, seven women with X chromosome monosomy, and five women with mosaicism of the X chromosome. Women with X chromosome trisomy (47, XXX) are at high risk for premature ovarian failure. Furthermore, women with X chromosome monosomy (45, X) are rarely infertile.29 However, pregnancy can occur in only 2-5% of patients with mosaic Turner syndrome, and partly conserved ovarian function is observed in approximately 30% of cases.30

Heterochromatin variants are commonly identified in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss, reproductive failure, and infertility. In this regard, variants of chromosomes 9 and 15 are the most frequent.31,32 In our study, normal chromosomal variants were observed in 1.68% of patients with infertility, with 15pstk and 9inv(9)(p11q13) being the most commonly identified chromosomal variants. In addition, heterochromatin chromosome 9qh + has been reported as the most common normal chromosomal variant.33 However, we did not find any infertile patients with the heterochromatin chromosome 9qh + variant. Despite the high prevalence of chromosomal normal variants in patients with infertility, the exact role or function of this abnormality remain unknown.34,35

Generally, we detected 114/3500 (3.257%) chromosomal abnormalities in Iranian couples with infertility. We showed that the prevalence of autosomal and sex chromosome abnormalities was higher in males. Our study highlighted the importance of cytogenetic studies in identification of infertility etiology in infertile patients, which can lead to the use of an appropriate therapeutic approach. We suggest cytogenetic investigation in infertile couples and subsequent genetic counseling in cases with chromosomal abnormalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating couples, gynecologists and urologist practices for data acquisition.

Competing Interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were undertaken in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institute and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendment. The study was performed with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and we obtained informed consent for this study from all participants.

References

- Mol BW, Tjon-Kon-Fat R, Kamphuis E, van Wely M. Unexplained infertility: is it over-diagnosed and over-treated?. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018; 53:20-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.09.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Azimi C, Khaleghian M, Farzanfar F. A retrospective chromosome studies among Iranian infertile women: Report of 21 years. Iran J Reprod Med 2013; 11(4):315-24. [ Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Sophie R, Imam AM, Khan FI, Ali SF, Shaikh A. Knowledge, perceptions and myths regarding infertility among selected adult population in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011; 11:760. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-760 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Isazadeh A, Hajazimian S, Rahmani SA, Mohammadoo-Khorasani M, Samanmanesh S, Karimkhanilouei S. The effects of factor II (rs1799963) polymorphism on recurrent pregnancy loss in Iranian Azeri women. Riv Ital Med Lab 2017; 13(1):37-40. doi: 10.1007/s13631-017-0145-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nasirpour H, Azari Key Y, Kazemipur N, Majidpour M, Mahdavi S, Hajazimian S. Association of rubella, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma infections with recurrent miscarriages in Bonab-Iran: a case-control study. Gene Cell Tissue 2017; 4(3):e60891. doi: 10.5812/gct.60891 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sayed Hajizadeh Y, Emami E, Nottagh M, Amini Z, Fathi Maroufi N, Hajazimian S, et al. Effects of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) gene 86 bp VNTR polymorphism on recurrent pregnancy loss: a case-control study. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2017;30(3). 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0010.

- Shiralizadeh J, Barmaki H, Haiaty S, Faridvand Y, Mostafazadeh M, Mokarizadeh N, et al. The effects of high and low doses of folic acid on oxidation of protein levels during pregnancy: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2017;33(3). 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0039.

- Yahaya TO, Oladele EO, Anyebe D, Obi C, Bunza MD, Sulaiman R. Chromosomal abnormalities predisposing to infertility, testing, and management: a narrative review. Bull Natl Res Cent 2021; 45(1):1-5. doi: 10.1186/s42269-021-00523-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- El-Dahtory F, Yahia S, Rasheed RA, Wahba Y. Prevalence and patterns of chromosomal abnormalities among Egyptian patients with infertility: a single institution’s 5-year experience. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2022; 27(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s43043-022-00101-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Fan HT, Zhang QS, Wang XY, Yang X, Tian WJ. Genetic screening and evaluation for chromosomal abnormalities of infertile males in Jilin province, China. Genet Mol Res 2015; 14(4):16178-84. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.8.7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Isazadeh A, Hajazimian S, Tariverdi N, Rahmani SA, Esmaeili M, Karimkhanilouei S. Effects of coagulation factor XIII (Val34Leu) polymorphism on recurrent pregnancy loss in Iranian Azeri women. J Lab Med 2017; 41(2):89-92. doi: 10.1515/labmed-2017-0012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pashaei M, Abdi A, Mousavi F, Bagherizadeh I, Dokhanchi A, Ghadami E. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in patients with consanguineous marriages referred to Sarem women’s hospital, Tehran, Iran. Sarem J Med Res 2021; 6(2):85-93. doi: 10.52547/sjrm.6.2.85.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vicdan A, Vicdan K, Günalp S, Kence A, Akarsu C, Işik AZ. Genetic aspects of human male infertility: the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities and Y chromosome microdeletions in severe male factor infertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004; 117(1):49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.07.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pylyp LY, Spinenko LO, Verhoglyad NV, Kashevarova OO, Zukin VD. Chromosomal abnormalities in patients with infertility. Cytol Genet 2015; 49(3):173-7. doi: 10.3103/s009545271503010x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kayed HF, Mansour RT, Aboulghar MA, Serour GI, Amer AE, Abdrazik A. Screening for chromosomal abnormalities in 2650 infertile couples undergoing ICSI. Reprod Biomed Online 2006; 12(3):359-70. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61010-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Serapinas D, Valantinavičienė E, Machtejevienė E, Bartkevičiūtė A, Bartkevičienė D. Evaluation of chromosomal structural anomalies in fertility disorders. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021; 57(1):37. doi: 10.3390/medicina57010037 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dul EC, Groen H, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM, Dijkhuizen T, van Echten-Arends J, Land JA. The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in subgroups of infertile men. Hum Reprod 2012; 27(1):36-43. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der374 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Clementini E, Palka C, Iezzi I, Stuppia L, Guanciali-Franchi P, Tiboni GM. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in 2078 infertile couples referred for assisted reproductive techniques. Hum Reprod 2005; 20(2):437-42. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh626 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Zeng Y, Yin B, Lin Q, Cai J, Zhang W. Study on the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in 10325 infertility patients who resort to IVF/ICSI. Fertil Steril 2009; 92(3):S14-5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.055 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gekas J, Thepot F, Turleau C, Siffroi JP, Dadoune JP, Briault S. Chromosomal factors of infertility in candidate couples for ICSI: an equal risk of constitutional aberrations in women and men. Hum Reprod 2001; 16(1):82-90. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.1.82 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Kurahashi H, Emanuel BS. Chromosomal translocations and palindromic AT-rich repeats. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2012; 22(3):221-8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kurahashi H, Inagaki H, Ohye T, Kogo H, Tsutsumi M, Kato T. The constitutional t( 11;22): implications for a novel mechanism responsible for gross chromosomal rearrangements. Clin Genet 2010; 78(4):299-309. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01445.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dana M, Stoian V. Association of pericentric inversion of chromosome 9 and infertility in romanian population. Maedica (Bucur) 2012; 7(1):25-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Ravel C, Berthaut I, Bresson JL, Siffroi JP. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in phenotypically normal and fertile adult males: large-scale survey of over 10,000 sperm donor karyotypes. Hum Reprod 2006; 21(6):1484-9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Anton E, Vidal F, Blanco J. Role of sperm FISH studies in the genetic reproductive advice of structural reorganization carriers. Hum Reprod 2007; 22(8):2088-92. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem152 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino F, Spizzichino L, Bono S, Biricik A, Kokkali G, Rienzi L. PGD for reciprocal and Robertsonian translocations using array comparative genomic hybridization. Hum Reprod 2011; 26(7):1925-35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der082 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fischer J, Colls P, Escudero T, Munné S. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) improves pregnancy outcome for translocation carriers with a history of recurrent losses. Fertil Steril 2010; 94(1):283-9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.060 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maiburg M, Repping S, Giltay J. The genetic origin of Klinefelter syndrome and its effect on spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril 2012; 98(2):253-60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.019 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Holland C. 47,XXX in an adolescent with premature ovarian failure and autoimmune disease. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2000; 13(2):93. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(00)00026-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chantot-Bastaraud S, Ravel C, Siffroi JP. Underlying karyotype abnormalities in IVF/ICSI patients. Reprod Biomed Online 2008; 16(4):514-22. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60458-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Suganya J, Kujur SB, Selvaraj K, Suruli MS, Haripriya G, Samuel CR. Chromosomal abnormalities in infertile men from southern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2015; 9(7):GC05-10. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2015/14429.6247 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sheth FJ, Liehr T, Kumari P, Akinde R, Sheth HJ, Sheth JJ. Chromosomal abnormalities in couples with repeated fetal loss: an Indian retrospective study. Indian J Hum Genet 2013; 19(4):415-22. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.124369 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Šípek A Jr, Mihalová R, Panczak A, Hrčková L, Janashia M, Kaspříková N. Heterochromatin variants in human karyotypes: a possible association with reproductive failure. Reprod Biomed Online 2014; 29(2):245-50. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.04.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sahin FI, Yilmaz Z, Yuregir OO, Bulakbasi T, Ozer O, Zeyneloglu HB. Chromosome heteromorphisms: an impact on infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet 2008; 25(5):191-5. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9216-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N, Le Bris MJ, Amice V, Le Martelot MT, Roche S. Chromosomal abnormalities in couples undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection. A study of 370 couples and review of the literature. Int J Androl 2004; 27(3):178-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00472.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]