Arch Iran Med. 26(9):529-541.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.78

Systematic Review

Attitude and Belief of Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care and Perception of Barriers; An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Mohammad E. Khamseh Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1

Zahra Emami Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, 1

Aida Iranpour Visualization, Writing – original draft, 2, *

Reyhaneh Mahmoodian Writing – original draft, 3

Erfan Amouei Formal analysis, Software, 4

Adnan Tizmaghz Software, 5

Yousef Moradi Formal analysis, 6

Hamid R Baradaran Methodology, Writing – review & editing, 1, 7

Author information:

1Endocrine Research Center, Institute of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Research Center for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, Institute of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Department of Internal Medicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

4Department of Internal Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5Department of Surgery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

6Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

7Ageing Clinical & Experimental Research Team, Institute of Applied Health Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, UK

Abstract

Background:

Obesity is a serious chronic disease that adversely affects health and quality of life. However, a significant percentage of people do not participate in or adhere to weight loss programs. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is needed to identify critical barriers to effective obesity management and to examine health practitioners’ attitudes and behaviors towards effective obesity treatment.

Methods:

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020. Eligible studies were identified through a systematic review of the literature using Medline, Scopus, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Embase databases from January 1, 2011 to March 2, 2021.

Results:

A total of 57 articles were included. Data on 12663 physicians were extracted from a total of 35 quantitative articles. Some of the most commonly perceived attitude issues included "obesity has a huge impact on overall health", "obesity is a disease" and "HCPs are to blame". Health professionals were more inclined to believe in "using BMI to assess obesity," "advice to increase physical activity," and "diet/calorie reduction advice." The major obstacles to optimal treatment of obesity were "lack of motivation", "lack of time" and "lack of success".

Conclusion:

Although the majority of health care professionals consider obesity as a serious disease which has a large impact on overall health, counseling for lifestyle modification, pharmacologic or surgical intervention occur in almost half of the visits. Increasing the length of physician visits as well as tailoring appropriate training programs could improve health care for obesity.

Keywords: Behavior, General practitioners, Obesity, Overweight, Physician, Primary health care

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Khamseh ME, Emami Z, Iranpour A, Mahmoodian R, Amouei E, Tizmaghz A, et al. Attitude and belief of healthcare professionals towards effective obesity care and perception of barriers; an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Iran Med. 2023;26(9):529-541. doi: 10.34172/aim.2023.78

Introduction

Obesity is a chronic and important disease with increasing prevalence. In 2016, more than 1.9 billion people over the age of 18 were overweight, of whom 650 million were obese. The global prevalence of obesity nearly tripled between 1975 and 2016.1 Additionally, only a minority of obese patients receive appropriate treatment, including lifestyle changes, pharmacological or surgical interventions.2-5 Much more attention must be paid to the critical role of medical staff in achieving optimal outcomes in managing obesity, despite well-known obstacles such as poor patient motivation, non-adherence to treatment, and short appointment times.6

Previous studies have shown that health professionals, including family physicians and general practitioners, lack sufficient understanding and competence regarding obesity, which is a barrier to effective obesity care.7 Since there are insufficient and inconsistent limited reviews, we performed this systematic review in order to explore the attitude and behavior of health-care professionals and perception of barriers towards effective obesity care.

Materials and Methods

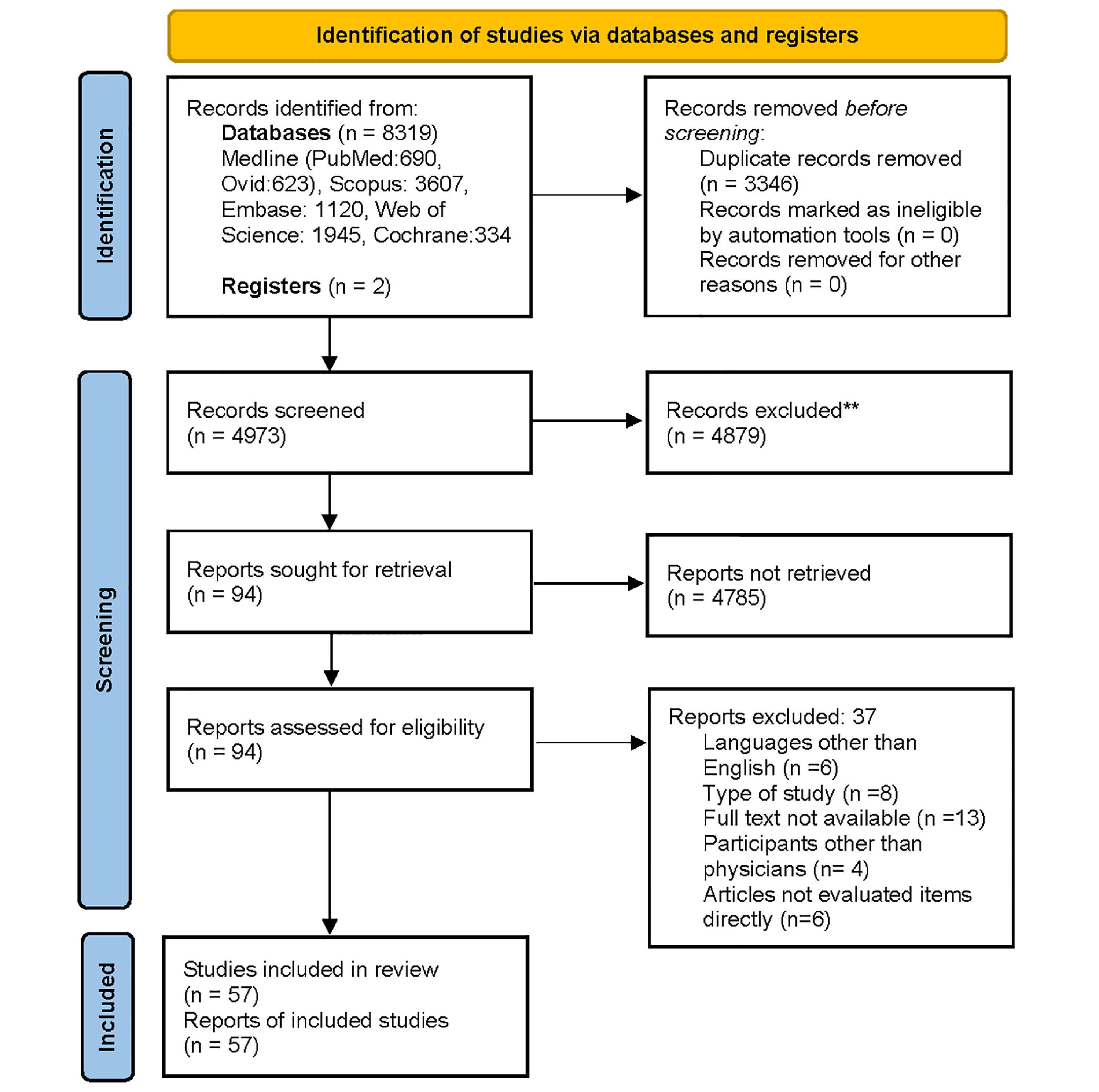

This systematic review was conducted in accordance withPreferred Reporting Items and checklist for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 (Figure 1) registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42020148596) and was approved by Ethical committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences. (Ethical code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.315)

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram for Systematic Reviews with Database and Register Searches Only

.

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram for Systematic Reviews with Database and Register Searches Only

We searched Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases from January 1, 2011 to March 2, 2021 to identify relevant reports. Gray literature, including Google Scholar, was also explored. The search terms selected according to Medical Subject Heading (MESH) terminology included: “Obesity”, “overweight”, “belief”, “barrier”, “attitude”, “behavior”, “behavior”, “Physician”, “General Practitioner”, “health care provider”, “health care worker” using AND/OR in title and abstract.

A preliminary database search using the Endnote program identified 8319 articles, including two articles identified through the gray literature sources (Google Scholar). After removing duplicates, 4973 records remained and were reviewed by two investigators. Of these, 4879 articles were excluded through title and abstract verification. The remaining 94 full-text articles were evaluated using the following inclusion criteria:

-

Articles on adult obesity (excluding pediatrics)

-

English-language articles

-

Observational studies including case-control studies, cross-sectional studies and cohort studies

-

Articles available in full text

-

Articles which directly assess attitudes, beliefs and barriers to obesity care

-

Articles addressing medical professionals including doctors (excluding articles about patients).

The reasons for excluding 37 records were: non-English language (n = 6), study type (n = 8), full text unavailable (n = 13), non-physician participants (n = 4), articles not relevant to aims of study (n = 6). Finally, we performed quality assessment of the remaining 57 articles using the JBI Critical Assessment Checklist for Cross-sectional Analysis Studies and scored on a 7-point scale.

Statistical Analysis

The DerSimonian-Liard random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence using the Metaprop command in Stata 16. Cochrane Q and I2 tests were used to evaluate the heterogeneity and variance between studies. We used the funnel chart and its graph to assess publication bias. All two-step statistical tests were considered at α = 0.05.

Results

A total of 57 articles were included between 2011 and 2020. Of these, 12 articles were on barrier perceptions, half of which (6 articles) provided quantitative statistical data and the rest identified barriers qualitatively. Thirty-one articles were on attitude, 22 of which focused on quantitative information, and the remaining nine articles addressed qualitative information. The remaining 14 articles were on beliefs, with half of them being quantitative, and the rest qualitative. Different data collection methods were used such as Personal interviews, Telephone contacts, and Responses to surveys.

A total of 35 quantitative articles were included (Table 1). The total number of participating physicians was 12 663. The largest study population was in the study of Steeves et al,8 which included 2022 individuals, and the smallest study population was in the study of McHale et al,9 which included 14 individuals.

Table 1.

Main Characteristics of the Included Studies

|

Chief Author

|

Year

|

Country

|

Participants

|

Response rate

|

Quality Assess (max=7)

|

Barriers

|

Attitude

|

Beliefs

|

| Steeves et al8 |

2014 |

USA |

2022 |

|

5 |

|

HCPs have responsibility.

Physician should be model or need a role model.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

|

| McHale et al9 |

2020 |

UK |

14 |

|

7 |

Failure to able or success |

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Patients were aware of the health risks.

Physician should be model or need to role model.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals.

Obesity is a disease. |

|

| Glauser et al10 |

2015 |

USA |

300 |

|

4 |

Failure to able or success

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Lack of interest

Lack of training

Stigma/feel uncomfortable or hard to talk |

Obesity is a disease.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

Use BMI to assess obesity |

| Thapa et al11 |

2014 |

USA |

52 |

92 |

3 |

|

Obesity is a disease.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

|

| Mkhatshwa et al12 |

2016 |

South Africa |

48 |

|

4 |

|

Obesity is a disease.

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Patients can lose weight. |

Counseling for lifestyle modification

Assess obesity and document it |

| Srivastava et al13 |

2018 |

USA |

61 |

41.8 |

3 |

|

Obesity is a disease.

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions. |

|

| Rurik et al14 |

2013 |

Hungary |

521 |

89 |

5 |

|

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Physician should be model or need to role model.

Obesity is a disease.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals. |

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Use BMI to assess obesity

Counseling for lifestyle modification |

| Dicker et al15 |

2020 |

Israel |

169 |

21 |

|

Lack of interest

Lack of motivation

More important concerns to discuss

Failure to able or success

Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talk

Lack of physicians’ confidence |

Obesity is a disease.

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

HCPs have responsibility.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals.

Patients can lose weight. |

|

| Epling et al16 |

2011 |

USA |

75 |

36.5 |

5 |

Lack of time

Lack of referral options or educational resources |

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions.

Obesity is a disease.

Educating patients is important.

Physician should be model or need to role model.

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Patients were aware of the health risks.

Patients can lose weight. |

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician |

| Huepenbecker et al17 |

2018 |

USA |

134 |

42 |

5 |

Lack of training

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Lack of motivation |

Educating patients is important.

HCPs have responsibility.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

|

| Leiter et al18 |

2015 |

United Kingdom |

335 |

42 |

3 |

|

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions.

Obesity is a disease.

Medical guidelines are effective.

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Patients were aware of the health risks. |

Refer to a nutritionist or dietician

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Screen and assess related risks and disease

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Prescription of weight loss medication

Counseling for weight loss surgery |

| Sebiany et al19 |

2013 |

Saudi Arabia |

130 |

87 |

5 |

Lack of training

Lack of compliance

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Lack of time

Failure to able or success

Lack of physicians’ confidence |

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions.

Obesity is a disease. |

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials |

| Simon et al20 |

2018 |

USA |

111 |

26 |

4 |

Lack of time

Lack of training

Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talk |

|

Assess obesity and document it

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Counseling for lifestyle modification

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Counseling for weight loss surgery

Refer to a nutritionist or dietician

Prescription of weight loss medication |

| Attalin et al21 |

2011 |

France |

203 |

80 |

4 |

Lack of compliance

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Lack of time

Failure to able or success

Lack of training |

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health. |

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Behavior therapy or psychotherapy

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician |

| Alshammari et al22 |

2014 |

Saudi Arabia |

130 |

87.2 |

5 |

|

Obesity is a disease.

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Physician should be model or need to role model.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals. |

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Use BMI to assess obesity

Screen and assess related risks and disease

follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Counseling for WL surgery

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician

Behavior therapy or psychotherapy

Prescription of WL medication |

| Petrin et al23 |

2017 |

USA |

1501 |

77 |

3 |

|

HCPs have responsibility.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

Screen and assess related risks and disease

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Start discussing or Motivational interviewing

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories |

| Sharma et al24 |

2019 |

Canada |

395 |

34 |

3 |

Lack of interest

Lack of time

Lack of motivation

More important concerns to discuss |

Obesity is a disease.

HCPs have responsibility.

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions.

Patients were aware of the health risks.

Medical guidelines are effective. |

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Screen and assess related risks and disease

Behavior therapy or psychotherapy

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician

Prescription of weight loss medication

Counseling for weight loss surgery |

| Tsai et al25 |

2017 |

USA |

272 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

| Kaplan et al26 |

2017 |

USA |

606 |

20.4 |

4 |

Lack of time

Lack of motivation

More important concerns to discuss

Lack of interest

Stigma/feel uncomfortable or hard to talking |

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

Obesity is a disease.

HCPs have responsibility.

Obesity has a large impact on overall health and is associated with serious medical conditions. |

Start discussing or Motivational interviewing

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Assess obesity and document it

Counseling for lifestyle modification

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician

Prescription of weight loss medication

Counseling for weight loss surgery |

| Hite et al27 |

2018 |

USA |

206 |

74 |

4 |

HCPs misdiagnosis

Lack of time

lack of physicians’ confidence

Lack of compliance

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talking |

Patients were aware of the health risks. |

Assess obesity and document it

Use BMI to assess obesity

Start discussing or Motivational interviewing

Screen and assess related risks and disease |

| Aleem et al28 |

2015 |

USA |

51 |

91 |

5 |

Lack of time

Lack of motivation

Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talk

More important concerns to discuss

Lack of training |

|

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Assess obesity and document it

Start discussing or Motivational interviewing

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician |

| Wong et al29 |

2018 |

Australia |

204 |

81.6 |

2 |

|

|

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician

Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials

Prescription of weight loss medication

Counseling for weight loss surgery |

| Turner et al30 |

2018 |

USA |

1506 |

64.5 |

5 |

|

Medical guidelines are effective. |

|

| Alzouebi et al31 |

2012 |

United Kingdom |

100 |

73 |

0 |

Lack of training |

|

|

| Aucott et al32 |

2011 |

United Kingdom |

194 |

51 |

3 |

|

Obesity is a disease. |

Assess obesity and document it |

| Granara et al33 |

2017 |

USA |

94 |

11 |

4 |

Failure to able or success

Lack of motivation

Lack of referral options or educational resources

Lack of training

Lack of time |

|

|

| Laidlaw et al34 |

2019 |

Scotland |

107 |

18.5 |

3 |

Lack of time

Lack of motivation

Lack of referral options or educational resources

More important concerns to discuss

Lack of training

Lack of physicians’ confidence |

A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health.

HCPs have responsibility.

Physician should be model or need to role model.

Obesity is a disease.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals. |

Use BMI to assess obesity |

| Look et al35 |

2019 |

USA |

606 |

|

5 |

|

|

Start discussing or Motivational interviewing |

| Mudi et al36 |

2019 |

Bangladesh |

300 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

| Saedon et al37 |

2015 |

Brunei |

77 |

85.6 |

6 |

|

Patients can lose weight.

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals.

Patients were aware of the health risks. |

|

| Sikorski et al38 |

2013 |

Germany |

682 |

|

6 |

|

|

|

| Smith et al39 |

2015 |

USA |

219 |

62 |

5 |

|

|

|

| Bąk-Sosnowska et al40 |

2015 |

Poland |

250 |

|

3 |

|

|

Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories

Start discussing or motivational interviewing

Counseling for increasing physical activity

Counseling for lifestyle modification

Screen and assess related risks and disease |

| Goranova-Spasova et al41 |

2020 |

Bulgaria |

154 |

|

5 |

Lack of physicians’ confidence

More important concerns to discuss

Lack of time

Lack of motivation |

Physicians’ role is to refer to professionals.

HCPs have responsibility.

|

|

BMI, body mass index; HCPs, health care providers; WL, weight loss.

Attitudes

Some of the most commonly identified attitudes between health care providers (HCPs) included:

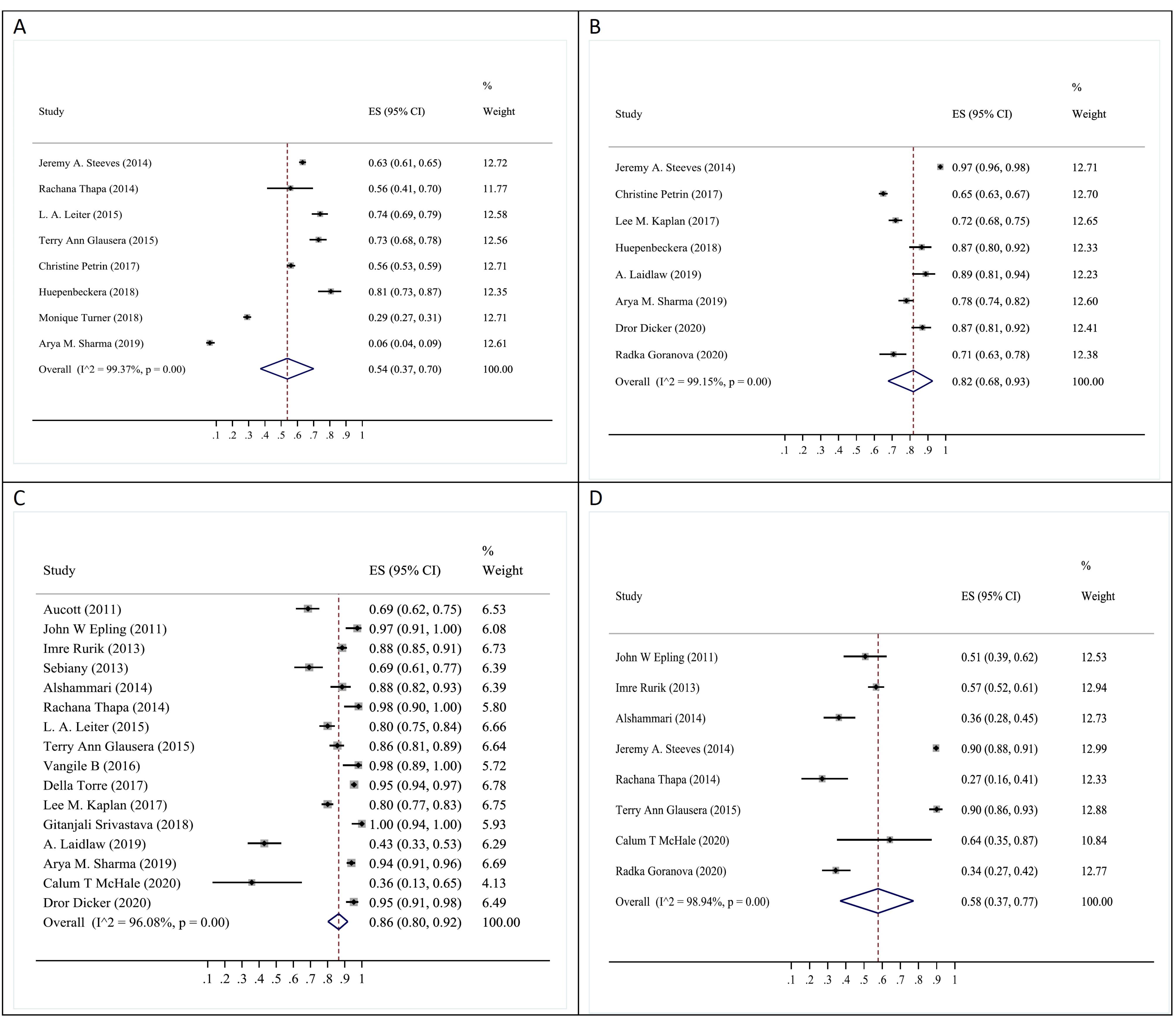

“Obesity has a significant impact on overall health and is associated with serious illness” (87%; 95% CI: 71‒98%), “Obesity is a disease” (86%; 95% CI: 80‒98%), and “HCPs are responsible for obesity in their communities” (82%; 95% CI: 68‒93%) (Figure 2 and Table 2; Supplementary file 1).

Figure 2.

The Pooled Prevalence of Attitude Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Medical guidelines is effective, B: HCPs have responsibility, C: Obesity is a disease, and D: HCPs management will success and feel confident)

.

The Pooled Prevalence of Attitude Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Medical guidelines is effective, B: HCPs have responsibility, C: Obesity is a disease, and D: HCPs management will success and feel confident)

Table 2.

The Quantitative Results and Pooled Prevalence of Scales Based on Meta-analysis Results

|

Status

|

Pooled Prevalence (%)

|

95 % CI (Lower and Upper)

|

| Barriers |

|

|

| Lack of motivation |

53 % |

39– 67 % |

| Lack of time |

46 % |

32 – 59 % |

| Lack of referral options or resources |

38 % |

21 – 56 % |

| Lack of training |

37 % |

16 – 60 % |

| More important concern to discuss |

38 % |

30 – 47 % |

| Lack of physician’s confidence |

19 % |

6 – 38 % |

| Failure to able or success |

42 % |

27 – 59 % |

| Stigma/feel uncomfortable or hard to talking |

14 % |

8 – 21 % |

| Attitude |

|

|

| Obesity has a large impact on overall health and associated with serious medical conditions |

87 % |

71 – 98 % |

| Obesity is a disease |

86 % |

80 – 98 % |

| HCPs have responsibility |

82 % |

68 – 93 % |

| A loss of 10% body weight would be beneficial to my overall health |

78 % |

61 – 91 % |

| Physician should be model or need to role model |

76 % |

64 – 86 % |

| HCPs management will success and feel confident |

58 % |

37 – 77 % |

| Medical guidelines are effective |

54 % |

37 – 70 % |

| Physician’s role is to refer to professionals |

53 % |

30 – 76 % |

| Patients were aware of the health risks |

39 % |

23 – 56 % |

| Beliefs |

|

|

| Using BMI to assess obesity |

78 % |

67 – 87 % |

| Counseling for increasing physical activity |

68 % |

53 – 81 % |

| Counseling for eating habits/reducing calories |

64 % |

51 – 76 % |

| Counseling or lifestyle modification |

61 % |

34 – 85 % |

| Discussing or Motivational interviewing |

57 % |

43 – 71 % |

| Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials |

53 % |

29 – 76 % |

| Assess obesity and document it |

55 % |

26 – 82 % |

| Screen and assess related risks and disease |

49 % |

18 – 80 % |

| Refer to visiting a nutritionist or dietician |

25 % |

13 – 40 % |

| Prescription WL medication |

10 % |

6 – 13 % |

| Counseling for WL surgery |

13 % |

4 – 24 % |

“10% weight loss helps overall health” (78%; 95% CI: 61‒91%), “Physicians should be or need to be role models” (76%; 95% CI: 64‒86%), “HCP leadership in obesity management is prosperous and secure” (58%; 95% CI: 37‒70%) (Figure 2 and Table 2; Supplementary file 1).

Funnel plots to assess publication bias are reported in Supplementary file 1.

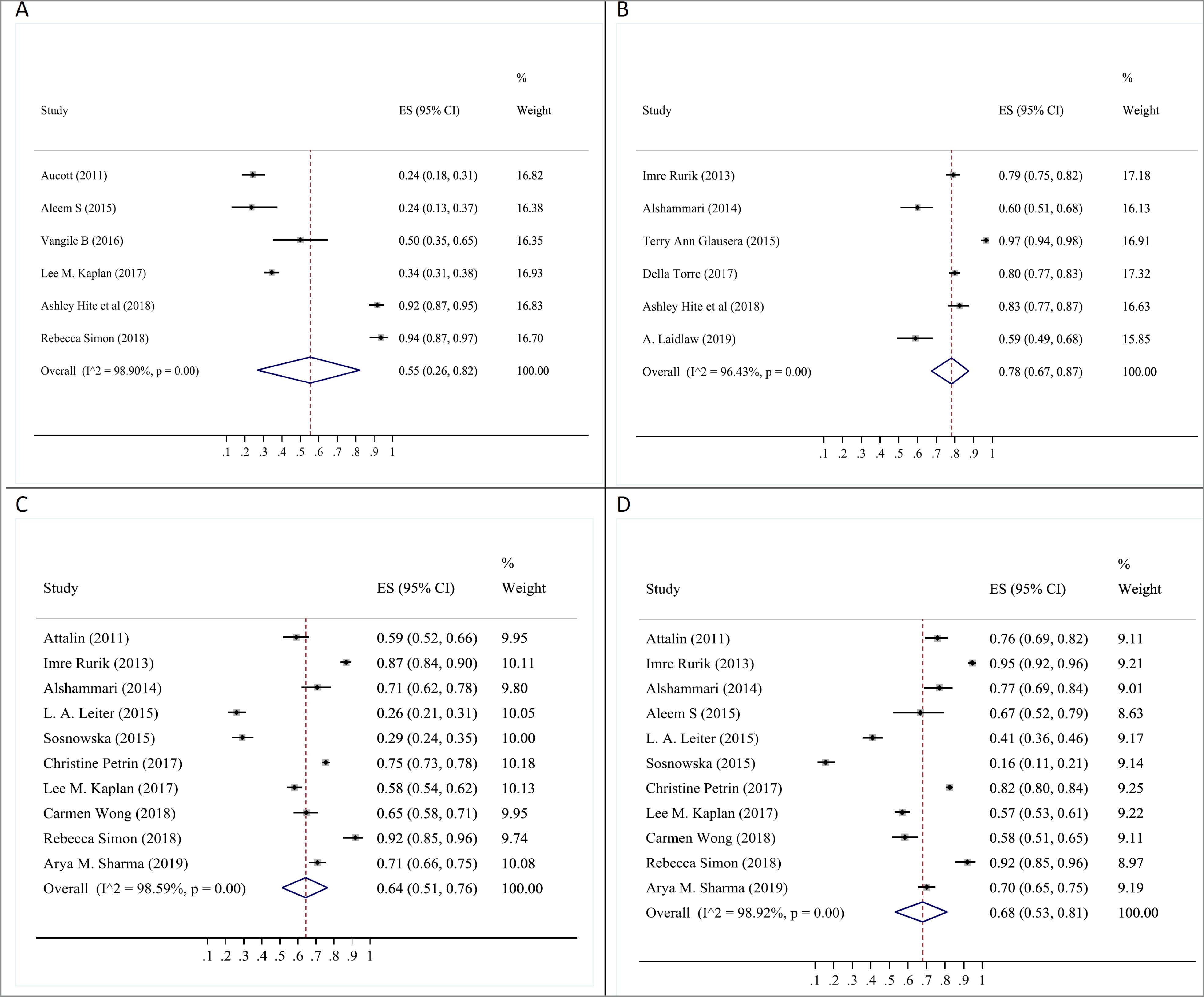

Beliefs

When considering quantitative data, the three most common beliefs were “BMI is used to assess obesity” (78%; 95% CI: 67‒87%), “Counseling to increase physical activity” (68%; 95% CI: 53–81%) and “Nutrition and calorie restricting advice” (64%; 95% CI: 51‒76%). Other common beliefs were related to «counseling to change lifestyle « (61%; 95% CI: 34‒85%), “Negotiation interview or Motivational interview” (57%; 95% CI: 43‒71%), “Follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials” (53%; 95% CI: 29‒76%), «Assessment and documentation of obesity» (55%; 95% CI: 26‒82%) and “Screening and Assessment of associated risks and conditions” (49%; 95% CI: 18‒80%) (Figure 3 and Table 2; Supplementary file 1). Funnel plots to assess publication bias are reported in Supplementary file 1.

Figure 3.

The Pooled Prevalence of Belief Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Assess obesity and document it, B: Use BMI to assess obesity, C: counselling for eating habits/reducing calories, and D: counselling for increasing physical activity)

.

The Pooled Prevalence of Belief Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Assess obesity and document it, B: Use BMI to assess obesity, C: counselling for eating habits/reducing calories, and D: counselling for increasing physical activity)

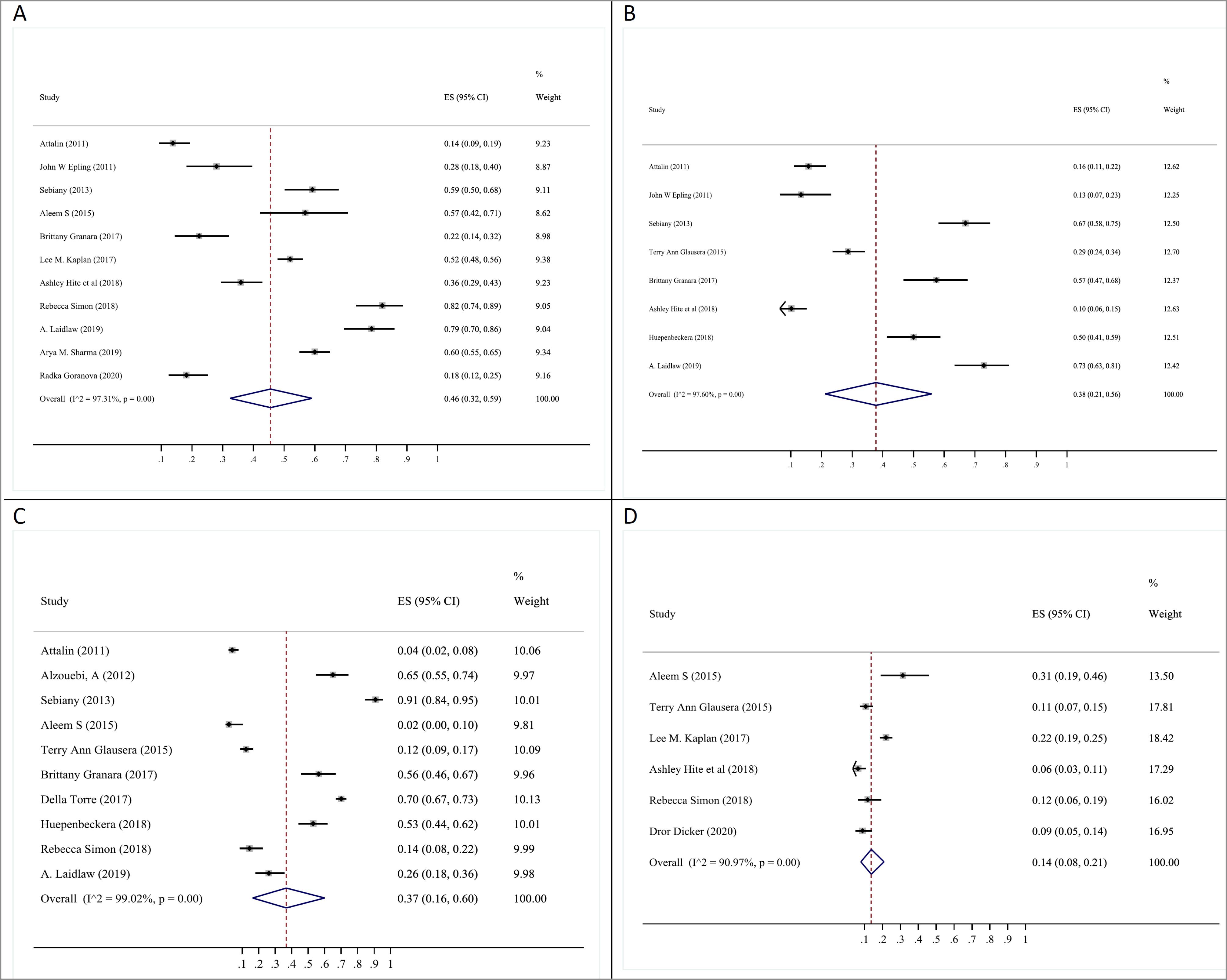

Barriers

The three biggest barriers to optimal obesity care were ‘lack of motivation’ (53%; 95% CI: 39‒67%), “I don’t have time” (46%; 95% CI: 32‒59%) and “Failure or inability to achieve the desired outcome” (42%; 95% CI: 27‒59%) (Figure 4, Table 2). Other barriers were “lack of education” (37%; 95% CI: 16-60%), “lack of referral facilities or resources” (38%; 95% CI: 21‒56%) and “having more important issues to discuss” (38%; 95% CI: 30‒47%) (Figure 4 and Table 2; Supplementary file 1).

Figure 4.

The Pooled Prevalence of Barriers Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Lack of time, B: Lack of referral options or educational resources, C: Lack of training, and D: Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talking)

.

The Pooled Prevalence of Barriers Scales in Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care (A: Lack of time, B: Lack of referral options or educational resources, C: Lack of training, and D: Stigma / feel uncomfortable or hard to talking)

Funnel plots to assess publication bias are reported in the Supplementary File. All of the qualitative studies mentioned that “lack of clearly specified practical guidelines and treatment options” are the main barriers. In addition, “limited understanding about obesity care, knowledge and skills” was the second major barrier.

Discussion

Belief and Attitude

Obesity-related beliefs and attitudes refer to conscious perceptions, interpretations, and thoughts or feelings of obesity that lead to understanding and learning. This may motivate HCPs to provide the highest quality care.11 The majority of physicians consider obesity as a disease; however, obesity is not just about increased BMI. It is associated with changes in anthropometrics, metabolic function, and gait parameters. Glauser et al reported that the majority of respondents used body mass index for obesity screening.10 Considering the limitations of BMI and the importance of central obesity, body fat distribution which is closely linked to metabolic complications should be taken into account.8 Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio could reliably distinguish central obesity from lower body and general obesity.42

Approaches to assessing obesity are multifaceted. Approximately 50% of physicians documented obesity as a problem, with attending physicians documenting obesity more frequently than residents (64% vs. 43%). On the other hand, normal-weight physicians reported obesity more frequently than overweight physicians (58% vs. 41%). Furthermore, doctors may not recognize obesity as a serious problem unless the patient’s BMI exceeds 35 kg/m2. Educational programs for health professionals are therefore needed to detect obesity early and increase the ratio of documentation. This could be a first step towards improving obesity management.11

Regarding the physicians’ perceptions of obesity, most HCPs and general practitioners (GPs) view obesity as a chronic disease. They also believe that obesity has a significant impact on overall health and is linked to serious medical conditions.11-13

In addition, the majority of health care professionals accept their responsibility to improve the situation and reducing the prevalence of this chronic disease. Moreover, they believe that they need to maintain a healthy weight in order to serve as a role model for their patients.14,15 However, a study by Tiexeira et al showed that although GPs believe that counseling obese patients about health risks is part of their job, their perception about their role in treating obesity is negative. The majority of doctors believe that they make no difference in getting their patients to make long-term lifestyle modification.7 Patient-centered communication, motivational interviewing, problem-solving, and action planning should be integrated into residency curricula and local continuing education programs.

Regarding interviews, Kirk et al showed that within the current healthcare system, HCPs are unable to provide the support obese people really need. They identified tensions within three themes expressed by groups of participants: “blame as a devastating relation of power, tensions in obesity management and prevention, and the prevailing medical management discourse”.43 These are reflected tensions and varying discourses surrounding obesity, namely obesity as a personal issue, obesity as a social construction, and obesity as a complex health condition. The study by Heintze et al showed that while almost all of the HCPs felt responsible for providing obesity-related care, they felt they are incompetent.44 Several factors that are related to physician characteristics, such as physician BMI and specialty, may explain this issue. For example, normal-weight physicians reported more confidence in counseling patients compared to their overweight peers. Additionally, obese patients also reported more trust in receiving weight loss advice from normal-weight physicians.44 Similar beliefs can be applied to many specialists. Pediatricians and obstetricians felt limited impact on treatment efficacy compared to other disciplines, and this finding may be considered in continuing medical education programs.

One of the important issues about attitude toward obesity is patient awareness. Physicians believe that nearly half of patients neither have the necessary knowledge about obesity and its harms, nor the ability to lose weight. Hence, they will lose the battle. That is why the majority of HCPs and GPs believe that patient education improves this situation.16,17 On the other hand, about half of the HCPs and GPs mentioned the need for updating the existing guidelines.10,17 On the other hand, the perception of physicians about treatment modalities is quite diverse. While about 54% of participants believe that current guidelines are effective,8,10,17,18 implementation of guidelines into daily practice is still far from the desired standards. Only half of the participants (53%) follow treatment guidelines or provide educational materials.14,19,20 As a rule, the combination of dietary modification and exercise is the most effective behavioral modality for the treatment of obesity. In this regard, over 60% of physicians provide advice to their patient to improve physical activity20-23 and make dietary modifications.20,23,24 Comparing different treatment modalities, many physicians expected larger weight loss with pharmacotherapy and surgery. The majority of primary care providers, endocrinologists, and cardiologists expected less weight loss with gastric bypass surgery while bariatric surgeons had a more reasonable expectation; a finding that could be explained by different educational and practical backgrounds.8,10 The study by Tsai et al revealed that physicians believe medication and surgery are less effective in comparison to lifestyle modification alone; thus, physicians who better understand the biology might be more open to using ‘biologic’ tools (medications and surgery). Perhaps, lack of valid and clear guidelines, as well as lack of proper awareness of the side effects and benefits of various interventions can play a role in this issue.25 Bleich et al confirm this fact that primary care physicians overwhelmingly supported additional training to improve nutrition and exercise counselling, optimal care related to bariatric surgery patients, as well as motivational interviewing.45 Primary care providers in this study also identified nutritionists/dietitians as the most qualified providers for obesity care.

Barriers to Optimal Obesity Management

Patient Factors

Lack of Motivation for Weight Loss and Lack of Compliance for Maintaining Long-term Lifestyle Changes

Obesity should be considered and managed as a medical condition that is progressive, chronic, and relapsing.46 In this study, nearly 54% of physicians believed that patients with obesity are not motivated enough to lose weight. In addition, almost 50% of healthcare professionals believe that people with obesity are non-compliant with long-term lifestyle changes. In a study by Kim et al in 2020, about 80% of people with obesity had experienced at least one serious weight-loss effort in the past.47 Interestingly, only 12% of these people had successfully lost near 10% of their body weight, half of whom kept it off for at least one year.47 The relatively high failure rate can be partially attributed to lack of long-term adherence to the obesity treatment. Therefore, despite successful weight loss after bariatric surgery, weight regain may occur, especially if they are less motivated and fail to adhere to long-term lifestyle changes. Thus, as with other chronic diseases, patients with obesity require to understand that obesity is a serious, chronic, relapsing recurring disease, and maintaining adherence to lifelong lifestyle changes is crucial for the long-term weight loss maintenance.

Lack of Referral Options or Resources (Misbelief and Misinformation Around Obesity Treatment) and Lack of Training

People with obesity have different attitudes and beliefs about obesity and its management. Interestingly, a great number of people with obesity prefer to seek advice from informal sources of information such as friends, family, and websites, rather than a qualified healthcare professional.47-49 According to this review, about 40% of healthcare professionals believe that patients with obesity would rather seek out medical advice themselves instead of visiting a licensed professional.

Stigma

Stigma is a common problem affecting the disabled community. Furthermore, it can lead to significant financial disadvantage; opportunities are denied and self-esteem is compromised. Many people with obesity feel that they are labelled as unmotivated, lazy, and uncooperative. According to this review, approximately 15% of health professionals reported having a negative attitude towards obesity. The negative attitude of health professionals towards obesity could be a potential barrier to optimal obesity care. Therefore, the medical profession should be more understanding, be compassionate with the patients and help them to lose weight. In addition, the negative attitudes of other members of the health care team and of course, the society towards the population with obesity need to be improved.50

Physician Factors

Lack of Time During General Practice Appointments

One of the most common obstacles to obesity management is limited length of the visits.51-54 Therefore, most physicians do not consistently address the issue of overweight or obesity directly with their patients.26,52,55 According to this review, about 46% of healthcare professionals indicated that they do not talk about weight management with their patients because they do not have enough time in their appointments.

HCPs Misdiagnosis and Lack of a Formal Diagnosis of Obesity

Sometimes, it is difficult for healthcare professionals to diagnose obesity by means of visual inspection alone and therefore, obesity may not be addressed during a patient care visit. According to this review, the accuracy of visual assessment of BMI was 45%. As a result, in order to appropriately diagnose and manage obesity, the BMI of a patient must be consistently calculated by all practitioners.27,56,57

Lack of Training and Obesity Counseling Competence (Lack of Expertise)

Although diet, nutrition, exercise, behavior therapy, and medication are among topics covered in obesity education for healthcare professionals, about 40% cited that they encountervarious challenges to aligning their clinical practice with current obesity management guidelines. This leads to the conclusion that most medical school curricula do not encompass sufficient obesity education and thus, medical schools must adequately address obesity education in their curricula, including adequate nutrition and obesity medication education.47,58,59

More Important Concern to Discuss

Discussions about the possible impacts of obesity on general health are a potentially disturbing and humiliating topic.51 In this study, almost 38% of the clinicians believed that there are moreimportant clinical issues to discuss during their appointment rather than weight management. The majority of healthcare professionals (62%) indicated that they are very willing to discuss weight control issues with patients, but report that there are obstacles to starting these conversations.

Lack of Physician’s Confidence

Physicians often report a lack of confidence in managing obesity. Among healthcare providers, physicians with a normal BMI are more confident in their capacity to provide patients with obesity diet, exercise, and counseling.45 About 22% of the physicians in this review expressed lack of confidence in their ability to manage obesity.

Conclusion

Evaluation of attitudes, beliefs and barriers toward effective obesity care revealed that although most of the physicians consider obesity as a serious disease which has a large impact on health, counseling for lifestyle modification, pharmacologic or surgical intervention occur in almost half of the visits. Therefore, tailoring appropriate training programs is needed in order to improve the attitude and perception of health care professionals about optimal obesity care.

Supplementary Files

Supplementary file 1 contains Figures S1-S3.

(pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Systematic Review Network and Dr. Neda Esmailzadehha for their help during this project.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The project was approved by Ethical committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.IUMS.REC.1398.929).

Funding

This work was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 2012; 307(5):491-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011; 378(9793):815-25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60814-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ 2012; 31(1):219-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kolotkin RL, Meter K, Williams GR. Quality of life and obesity. Obes Rev 2001; 2(4):219-29. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00040.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016; 22 Suppl 3:1-203. doi: 10.4158/ep161365.gl [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Teixeira FV, Pais-Ribeiro JL, da Costa Maia ÂR. Beliefs and practices of healthcare providers regarding obesity: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2012; 58(2):254-62. [ Google Scholar]

- Steeves JA, Liu B, Willis G, Lee R, Smith AW. Physicians’ personal beliefs about weight-related care and their associations with care delivery: the US National Survey of Energy Balance Related Care among Primary Care Physicians. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015; 9(3):243-55. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.08.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McHale CT, Laidlaw AH, Cecil JE. Primary care patient and practitioner views of weight and weight-related discussion: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2020; 10(3):e034023. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034023 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Glauser TA, Roepke N, Stevenin B, Dubois AM, Ahn SM. Physician knowledge about and perceptions of obesity management. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015; 9(6):573-83. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.02.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thapa R, Friderici J, Kleppel R, Fitzgerald J, Rothberg MB. Do physicians underrecognize obesity?. South Med J 2014; 107(6):356-60. doi: 10.14423/01.SMJ.0000450707.44388.0c [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mkhatshwa VB, Ogunbanjo GA, Mabuza LH. Knowledge, attitudes and management skills of medical practitioners regarding weight management. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2016; 8(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1187 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Srivastava G, Johnson ED, Earle RL, Kadambi N, Pazin DE, Kaplan LM. Underdocumentation of obesity by medical residents highlights challenges to effective obesity care. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018; 26(8):1277-84. doi: 10.1002/oby.22219 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rurik I, Torzsa P, Ilyés I, Szigethy E, Halmy E, Iski G. Primary care obesity management in Hungary: evaluation of the knowledge, practice and attitudes of family physicians. BMC Fam Pract 2013; 14:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-156 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dicker D, Kornboim B, Bachrach R, Shehadeh N, Potesman-Yona S, Segal-Lieberman G. ACTION-IO as a platform to understand differences in perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of people with obesity and physicians across countries - the Israeli experience. Isr J Health Policy Res 2020; 9(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s13584-020-00404-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Epling JW, Morley CP, Ploutz-Snyder R. Family physician attitudes in managing obesity: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4:473. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-473 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huepenbecker SP, Wan L, Leon A, Rosen D, Hoff J, Kuroki LM. Obesity counseling in obstetrics and gynecology: provider perceptions and barriers. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2019; 27:31-4. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2018.12.001.[French] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Leiter LA, Astrup A, Andrews RC, Cuevas A, Horn DB, Kunešová M. Identification of educational needs in the management of overweight and obesity: results of an international survey of attitudes and practice. Clin Obes 2015; 5(5):245-55. doi: 10.1111/cob.12109 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sebiany AM. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and perceived barriers in the management of overweight and obesity. J Family Community Med 2013; 20(3):147-52. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.121972 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Lahiri SW. Provider practice habits and barriers to care in obesity management in a large multicenter health system. Endocr Pract 2018; 24(4):321-8. doi: 10.4158/ep-2017-0221 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Attalin V, Romain AJ, Avignon A. Physical-activity prescription for obesity management in primary care: attitudes and practices of GPs in a southern French city. Diabetes Metab 2012; 38(3):243-9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.12.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari YF. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the management of overweight and obesity in eastern Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2014; 8(2):151-8. doi: 10.12816/0006081 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Petrin C, Kahan S, Turner M, Gallagher C, Dietz WH. Current attitudes and practices of obesity counselling by health care providers. Obes Res Clin Pract 2017; 11(3):352-9. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2016.08.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharma AM, Bélanger A, Carson V, Krah J, Langlois MF, Lawlor D. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity management in Canada: results from the ACTION study. Clin Obes 2019; 9(5):e12329. doi: 10.1111/cob.12329 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tsai AG, Histon T, Kyle TK, Rubenstein N, Donahoo WT. Evidence of a gap in understanding obesity among physicians. Obes Sci Pract 2018; 4(1):46-51. doi: 10.1002/osp4.146 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kaplan LM, Golden A, Jinnett K, Kolotkin RL, Kyle TK, Look M. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: results from the national ACTION study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018; 26(1):61-9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22054 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hite A, Victorson D, Elue R, Plunkett BA. An exploration of barriers facing physicians in diagnosing and treating obesity. Am J Health Promot 2019; 33(2):217-24. doi: 10.1177/0890117118784227 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aleem S, Lasky R, Brooks WB, Batsis JA. Obesity perceptions and documentation among primary care clinicians at a rural academic health center. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015; 9(4):408-15. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.08.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Harrison C, Bayram C, Miller G. Assessing patients’ and GPs’ ability to recognise overweight and obesity. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40(6):513-7. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12536 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Jannah N, Kahan S, Gallagher C, Dietz W. Current knowledge of obesity treatment guidelines by health care professionals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018; 26(4):665-71. doi: 10.1002/oby.22142 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alzouebi A, Law P. Attitudes to obesity in pregnancy. In: BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. Vol 119. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. p. 68-9.

- Aucott LS, Riddell RE, Smith WC. Attitudes of general practitioner registrars and their trainers toward obesity prevention in adults. J Prim Care Community Health 2011; 2(3):181-6. doi: 10.1177/2150131911401029 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Granara B, Laurent J. Provider attitudes and practice patterns of obesity management with pharmacotherapy. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017; 29(9):543-50. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12481 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw A, Napier C, Neville F, Collinson A, Cecil JE. Talking about weight talk: primary care practitioner knowledge, attitudes and practice. J Commun Healthc 2019; 12(3-4):145-53. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2019.1646061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Look M, Kolotkin RL, Dhurandhar NV, Nadglowski J, Stevenin B, Golden A. Implications of differing attitudes and experiences between providers and persons with obesity: results of the national ACTION study. Postgrad Med 2019; 131(5):357-65. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1620616 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mudi SR, Datta PK, Mudi N, Saha SK, Ali M, Arslan MI. Assessment of physicians’ knowledge to combat obesity in Bangladesh. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2019; 13(4):2393-7. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.06.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Saedon M, Naing L. General practitioners’ attitudes towards obesity in Brunei Darussalam. Brunei Int Med J 2015; 11(1):14-22. [ Google Scholar]

- Sikorski C, Luppa M, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Attitudes of health care professionals towards female obese patients. Obes Facts 2013; 6(6):512-22. doi: 10.1159/000356692 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, Jackson B, Antognoli E, Krejci SA. Primary care residents’ knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived professional norms regarding obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling. J Grad Med Educ 2015; 7(3):388-94. doi: 10.4300/jgme-d-14-00710.1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bąk-Sosnowska M, Skrzypulec-Plinta V. Health behaviors, health definitions, sense of coherence, and general practitioners’ attitudes towards obesity and diagnosing obesity in patients. Arch Med Sci 2017; 13(2):433-40. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58145 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goranova-Spasova R, Milcheva H, Hasanaj M. Overweight and obesity: knowledge, attitudes and practices of doctors in Bulgaria. J Hyg Eng Des 2020; 31:122-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Ghesmaty Sangachin M, Cavuoto LA, Wang Y. Use of various obesity measurement and classification methods in occupational safety and health research: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Obes 2018; 5:28. doi: 10.1186/s40608-018-0205-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kirk SF, Price SL, Penney TL, Rehman L, Lyons RF, Piccinini-Vallis H. Blame, shame, and lack of support: a multilevel study on obesity management. Qual Health Res 2014; 24(6):790-800. doi: 10.1177/1049732314529667 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heintze C, Sonntag U, Brinck A, Huppertz M, Niewöhner J, Wiesner J. A qualitative study on patients’ and physicians’ visions for the future management of overweight or obesity. Fam Pract 2012; 29(1):103-9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr051 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open 2012;2(6). 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871.

- Lim S, Oh B, Lee SH, Kim YH, Ha Y, Kang JH. Perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers to effective obesity care in South Korea: results from the ACTION-IO study. J Obes Metab Syndr 2020; 29(2):133-42. doi: 10.7570/jomes20013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim TN. Barriers to obesity management: patient and physician factors. J Obes Metab Syndr 2020; 29(4):244-7. doi: 10.7570/jomes20124 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wallis JA, Ackerman IN, Brusco NK, Kemp JL, Sherwood J, Young K. Barriers and enablers to uptake of a contemporary guideline-based management program for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2020; 2(4):100095. doi: 10.1016/j.ocarto.2020.100095 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Kalra S. Quinary prevention and bariatric surgery. J Pak Med Assoc 2020; 70(9):1664-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa SJ. Stigma of obesity: a major barrier to overcome. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2014; 1(3):73-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2014.06.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Glenister KM, Malatzky CA, Wright J. Barriers to effective conversations regarding overweight and obesity in regional Victoria. Aust Fam Physician 2017; 46(10):769-73. [ Google Scholar]

- Mauro M, Taylor V, Wharton S, Sharma AM. Barriers to obesity treatment. Eur J Intern Med 2008; 19(3):173-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.09.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sooknarine-Rajpatty J, A BA, Doyle F. A systematic review protocol of the barriers to both physical activity and obesity counselling in the secondary care setting as reported by healthcare providers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(4):1195. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041195 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huq S, Todkar S, Lahiri SW. Patient perspectives on obesity management: need for greater discussion of BMI and weight-loss options beyond diet and exercise, especially in patients with diabetes. Endocr Pract 2020; 26(5):471-83. doi: 10.4158/ep-2019-0452 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Burgess E, Hassmén P, Pumpa KL. Determinants of adherence to lifestyle intervention in adults with obesity: a systematic review. Clin Obes 2017; 7(3):123-35. doi: 10.1111/cob.12183 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dhurandhar NV, Kyle T, Stevenin B, Tomaszewski K. Predictors of weight loss outcomes in obesity care: results of the national ACTION study. BMC Public Health 2019; 19(1):1422. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7669-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Salvador J, Vilarrasa N, Poyato F, Rubio M. Perceptions, attitudes, and barriers to obesity management in Spain: results from the Spanish cohort of the international ACTION-IO observation study. J Clin Med 2020; 9(9):2834. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092834 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arora A, Poudel P, Manohar N, Bhole S, Baur LA. The role of oral health care professionals in preventing and managing obesity: a systematic review of current practices and perceived barriers. Obes Res Clin Pract 2019; 13(3):217-25. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2019.03.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Butsch WS, Kushner RF, Alford S, Smolarz BG. Low priority of obesity education leads to lack of medical students’ preparedness to effectively treat patients with obesity: results from the US medical school obesity education curriculum benchmark study. BMC Med Educ 2020; 20(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-1925-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]