Arch Iran Med. 25(1):71-75.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2022.10

History of Medicine in Iran

Spanish Flu in Tehran from 1918 to 1920

Seyyed Alireza Golshani 1  , Mohammad Ebrahim Zohalinezhad 2, *

, Mohammad Ebrahim Zohalinezhad 2, *  , Fatemeh Amoozegar 3

, Fatemeh Amoozegar 3  , Mojtaba Farjam 4

, Mojtaba Farjam 4

Author information:

1History of Iran after Islam, Department of Persian Medicine, School of Persian Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Ardakan, Yazd, Iran

2Persian Medicine, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3Student Research Committee, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran

4Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Mohammad Ebrahim Zohalinezhad, Persian Medicine, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Tel:+98 917 302 6200. Email:

zohalinm@sums.ac.ir

Abstract

The Spanish flu spread from September 23, 1918 to 1920. This disease was one of the historical catastrophes in Iran, and a large number of people in Tehran were infected. Evidence also shows that 5000–10000 out of the 250000 infected people died in Tehran over three years. Besides, an increase was detected in the prevalence of other diseases such as pericarditis, orchitis, mastoiditis, meningitis, optic neuritis, paralysis of the palate, mania, cholera, and dysentery. Overall, five percent of the city were destroyed, and the population and economic development were severely damaged. This study aims to evaluate the importance of the history of local medicine in Tehran, the spread of Spanish flu, World War I, and presence of Russian, Ottoman, and British troops in Iran during the flu outbreak. The critical role of Britain in artificial famine, malnutrition, and drug embargo was assessed, as well.

Keywords: Spanish Flu, Tehran, Iran, England, Ottoman, Russia

Copyright and License Information

© 2022 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Golshani SA, Zohalinezhad ME, Amoozegar F, Farjam M. Spanish flu in tehran from 1918 to 1920. Arch Iran Med. 2022;25(1):71-75. doi: 10.34172/aim.2022.10

Introduction

The Spanish flu in 1918 was the deadliest epidemic. About 500 million people worldwide, i.e., almost one-third of the world’s population, were infected and nearly 20-50 million people including around 675 000 Americans died. At first, the disease spread to Europe, the United States, and some parts of Asia. Then, it spread rapidly worldwide. At that time, there was no effective drug or vaccine to treat this type of severe flu. Therefore, citizens were advised to wear masks, and schools, theaters, and businesses were closed, and corpses were collected.1,2

Influenza is a virus that attacks the respiratory tract. The flu virus is highly contagious. In other words, when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, airborne droplets remain in the air that can be inhaled by anyone, resulting in infection with the virus.2

During the First World War, a revolution occurred in Russia in October 1917. When the Tsarist Russia was involved in the civil war from 1917 to 1922, a country called the Soviet Union was established. At that time, influenza was transmitted from the United States soldiers to the Russian troops and caused a large number of deaths. This outbreak might be one of the main reasons that caused the Russian government to withdraw from the war on March 3, 1918 and to sign the ceasefire agreement as well as the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Under these treaties, Russia denied the claims that led to the war, accepted the independence of Ukraine, Georgia, Poland, and Finland, and withdrew its claims to the Baltic states and some parts of the Ottoman Empire, the Caucasus, and Asia.3,4 However, sick Russian forces transmitted the disease to the Caucasus, north and west of Iran, and the Ottoman Empire.5

Influenza in Iran

Iranians were familiar with influenza since centuries ago, and Persian scholar physicians such as Rhazesand Avicenna discussed this disease in some parts of their books (Al- Hawawi and Qanun).6,7 Although later physicians wrote few documents about this disease, Willem Marius Floor, as a historian, linguist, writer, and Iran expert, reported several influenza outbreaks in the Middle East and Iran. According to his investigations, this disease or a similar one appeared in Iran in 855 AD, in Baghdad in 1654, in Basra in 1753, in Iran, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey in the winter of 1833, and in Iran in October 1854.8,9 The other similar disease which spread in the winter of 1877 and 1878 was equine influenza, which was named Mashmasheh in Persian. This disease caused up to three percent of the infected foreign people to die in Iran, but the exact number of Iranian casualties remains unreported. According to Willem Floor’s statements, it could be accurately claimed that influenza spread as an epidemic in Iran in 1890, 1891, 1895, 1897, 1910, 1912, and 1913, resulting in an expected mortality rate among the Iranian population. However, the severity of those outbreaks was not the same as that of the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918. Therefore, few researchers, physicians, and historians wrote about those outbreaks.8 Mirza Abdul Hussein Tabrizi Zenozi (Philosoph al- Dawlah) (1861–1941) was one of the few doctors who wrote an important manuscript about the flu and modern remedies in 1891.10 Another physician who wrote a few clinical experiences about the Spanish flu was Dr. Abdullah Ahmadiyya (1886–1959) who wrote a book titled “Raz-e-Darman” (the Secret of Healing) after the outbreak of the Spanish flu in Iran, referring to the history of patients with the flu as well as their treatment methods.11

The initial outbreak of the Spanish flu in Khorasan was transmitted from Ashgabat in Turkmenistan to Mashhad in August 1918.6,12 This outbreak coincided with a cold hurricane, and nearly 500 people died in Mashhad within one month. Elderly and poor people were more susceptible to the disease and were at risk of death.12,13 At that time, about 70 000 out of the 100 000 people in Mashhad became ill, leading to almost 3500 deaths. Besides, mortality rates of 5% and 7% were reported in Mashhad and the surrounding villages, respectively. After that, it was transmitted to the western and southern areas including Tehran, Birjand, Sistan, and Yazd.6,12 Tabriz in the northwest of Iran was also infected through the Jolfa-Tbilisi railway from the Caucasus in September.6 The Russians transmitted the disease to the Ottoman troops, too. After the invasion of the Ottoman forces towards Kurdistan and Azerbaijan located in the west and northwest of Iran, the disease appeared in Hamadan, Qazvin, Rasht, and Tehran in September.6

Influenza in Tehran

For the first time, influenza spread in Tehran at the end of the Fath-Ali Shah Qajar’s reign (1772–1833) in 1833. The influenza outbreak was transmitted from the Russian troops to the north of Iran and subsequently to Tehran. Cyril Lloyd Elgood (1893–1970), who was a British historian and the British Embassy physician in Tehran in 1925-1933, reported the death of more than a dozen people, “Dead bodies and patients in severe conditions were seen on the streets, and the condition was much worse than the one observed in plague and cholera. Furthermore, bread and meat were scarce and inedible, and the fear of a general famine was quite present”.14,15

According to the statements of Willem Floor, the population of Tehran was about 250 000, and about 2000 infected people died from the Spanish flu epidemic over three months. The disease suddenly spread on September 22, 1918.6 When a severe westerly wind blew on 24 September, the public opinion was that the wind had caused the disease, and they named it the “wind disease”. The relationship between the disease and the “wind” was an ancient belief, which has also been found in different types of traditional medicines such as Unani medicine, Ayurveda, and Persian medicine. It has been mentioned in Indian and Persian religious books such as Vendidad and Rig Veda, as well. In this context, it is interesting to know that the origin of the word ‘influenza’ in Italy means celestial catastrophe, impact, and influence of stars.6

This disease appeared in Qazvin on September 15. Hence, travelers from Qazvin might have transmitted it to Tehran.6 The British Embassy declared on October 14 that the severe flu in Tehran had been spread three weeks ago,

“Due to the sickness of the king, I could not visit him. The Prime Minister is currently recovering”.6

A daily report of one patient showed the rapid spread of the disease. That patient left Tehran when the flu had not yet spread there and arrived in Qazvin on the same day. After one day, he fell ill and had all the common symptoms and returned to Tehran on the third day. The epidemic spread in the city within one or two days after the severe wind.6 A Qajar Prince (Ein al- Saltana) said in the book of memoirs, “Based on some letters sent from Qazvin, all people were safe at night, though two-thirds of them became sick on the following day, and the shops and offices were closed. At first, I did not believe it, but now the truth of that report has become clear. We have the same issues in our village, but nobody pays attention to it due to the lack of a (strong) community. According to Mir Mohammad Hossein Khan (a Qajar Prince) who also suffered from the disease, the name of this disease is “influenza,” which appeared in Europe and Iran several years ago and killed an incredible number of people. It was named “Mashmasheh” [sporadic] in Iran. Although this disease infected people sporadically, nobody has seen a condition like this until now. Therefore, it does not have any names”.16

Indigenous physicians found that the patients who were out of their homes on that day became ill suddenly. The mortality rate was higher among poor people. Shrouds were carried on handcarts, and corpses were piled up in cemeteries. The lowest number of casualties was 2000 in three months. Rare diseases such as pericarditis, orchitis, mastoiditis, meningitis, optic neuritis, palatoplegia, and mania were reported, as well. Bloody diarrhea was also prevalent. Fresh air had no preventive effects, and all the eighty Englishmen who worked in the transport system and lived outdoors were infected. They were treated in a field tent without any complications, except for one who was very weak and incapacitated and died due to bronchopneumonia. Rural areas were also severely affected.6 Qahreman Mirza Salour Eyn - Saltaneh (1872–1945) was the second child of Prince Abdul Samad Mirza Izz al- Dawlah ibn Muhammad Shah Qajar, the nephew of Nasser al-Din Shah (1831-1896). He described in details in his book the epidemic of influenza in Tehran and its history, “The warm wind blew for more than two hours. Then, it rained a little. The air was clear and a little cold at night. The next day, the epidemic of influenza became severe in Tehran. Finally, everyone was infected. Markets, schools, and offices were closed. Influenza was a highly contagious disease, and it spread very quickly. It appeared in Italy in 1722 and was named the flu. In the twelfth century, the disease was identified completely, and it was often observed in Europe. It gradually spread around the world from 1889 to 1890”....16 Then, Ein al- Saltanah explained the disease on the battlefields of World War I, “...we do not have any pharmacists or pharmacies to prepare drugs and treat ourselves. Some of our traitorous compatriots also help armed gangs and foreign political attackers to advance and reach their armed and diplomatic goals easily. The condition of the society is not suitable and we have different problems such as much dust on the streets and alleys, which are associated with shopkeepers’ poor hygiene while providing food. All these factors have exacerbated the real power of the disease by more than ten times, leading to the disease outbreak. Consequently, unfortunate inhabitants have been led to the brink of extinction in this country, and it can be the last doom for people of poor countries. The ineffective nation cannot resist any opposition or aggression. Generally, when a nation is deprived of the ability to live, it is dominated by new issues. These new issues could be Russian, English, and Turkish armies as well as the flu…”.1 He also wrote, “Iran welcomes any uninvited guests. Who can tell why you came or why you went. Evidence showed that Iran was hospitable and patriotic in history, and Iranians accepted the rules of Greeks, Afghans, Arabs, Parthians, and Mongols in their country with different excuses; one was related to the Kianian descent, another was Achaemenian, and another was attributed to different names. Based on these documents and reasons, they agreed with these conditions and accepted other similar conditions like the outbreak of the flu and other related factors again. Now, the same environment and ethics will fight you. So, you cannot find answers to these questions; why a stranger came to this country, why a stranger entered this ruin, and (how) the winds and storms passed the Alborz mountains and transmitted the flu to Iran, in such a way that it spread all over the country and destroyed everything. Many people suffered. No one went to bakeries, but many people went to drugstores and watermelon shops. However, are we allowed to say why no one has been found to prevent the flu?”.16

In another part of his memories, Ein al- Saltanah mentioned the disease on the battlefields of World War I and said,

“It was reported that 1800 German soldiers were infected with the flu and died on the battlefield of Morocco. Then, severe winds blew all over Iran and caused people to be infected with bronchitis, fever, and muscle aches. The real pathway of that wind did not matter. However, we argued that the disease was related to Allied or Axis forces! Some people believed that Allied forces caused this disease to spread in Iran and that it had to be treated. Others said that because the disease had passed from the countries of Axis forces, it was a familiar and friendly disease that had to be liked without being tackled!”.16

He also evaluated the social approach towards the disease and asked people to be wise,

“I addressed the socially ill and miserable people; you should clean nasty situations in your country, not like the flu, and search for its treatment. I said this for you and your children, not for the flu and bronchitis. The physician is not friendly with the flu and is not the enemy of bronchitis. The physician just likes you and cares for you, so you have to like yourself. Influenza is not contagious in an ignorant nation and does not have a severe effect, but a misconception can be very harmful. After the flu, symptoms such as chest pain, weakness, and muscle aches remained in a patient for a while (we should be aware of that). Distributing a corrupt opinion and issuing a false report persist as post-flu symptoms for a while, and their effects will remain in mind. Therefore, the social nurse (an allegory of government officials) must be wise to remove the disease from the national bodies. We had nothing, and we were accustomed to misery and nothingness. We were afraid of the proper lifestyle and happiness. Other nations of the world did their job and defeated it. It was said that the happy and the misfortunate knew their responsibilities and performed their duties. In the future, the facts will be clear. However, we never understand what we should do”.16

Ein al- Saltanah also analyzed the harms and disadvantages of influenza,

“The only problem in Iran was the flu. Stealing, looting, and famine were common problems, and we were used to them. Since last year, 200 000 people have died in Tehran and the surrounding areas. In order to determine the financial cost of this disease, we should know that if we consider the cost of the funeral of each person as 10 Tomans and the cost of treatment of each person as about 50 Tomans, this disease has caused a loss of ten crores of Tomans. (1 toman = 10 Qirans = 300 $ (during Qajar government), 1 (Persian) corores = 500 000). There was no need for treatment if the corores had been appropriately taken from the people and kept away from the looting and theft environment for the health and cleanliness of the city and water pipes. In this way, the financial condition of the country would not be endangered. These were the damages that affected Tehran. The news and information coming from other cities, especially of the windy illness, is so horrible that it is not an exaggeration to assume that one-third or half of the country’s entire population will die by the end of this year. One of the physicians considers Tehran to be the center of Typhus due to the ruins and polluted rivers and believes that it is impossible to live together in this way. The government just ordered to allocate twelve Qirans (which was the currency of Iran during the Qajar government and is equal to $30 US) to the burial of the dead people with no families”16 (Figure 1).

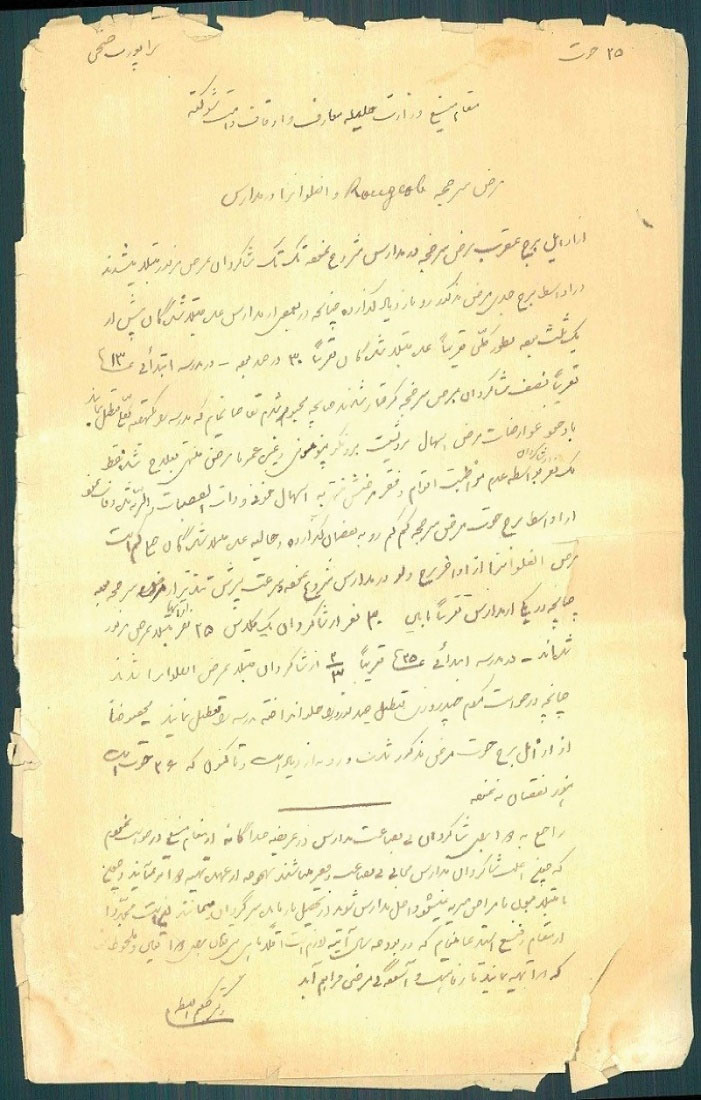

Figure 1.

Dr. Aliakbar Khan Etemadzadeh Hakim al-Saltaneh provided the report based on the outbreak of measles, influenza, and other diseases in Tehran’s schools (archive of documents and national library of Iran).

.

Dr. Aliakbar Khan Etemadzadeh Hakim al-Saltaneh provided the report based on the outbreak of measles, influenza, and other diseases in Tehran’s schools (archive of documents and national library of Iran).

When the Spanish flu was transmitted to Iran, Britain caused a significant famine. Many families, friends, and acquaintances lost their lives and experienced poverty, hunger, and starvation. The immune systems of the people who survived the famine were severely weakened, and some people were infected with other diseases.17-19 At the end of the famine period, use of opium became more common amongst people, which could further weaken the immune system. The British government commissioned their forces to addict the Iranian people who suffered from diseases and poverty. Hence, they prescribed opium as a treatment for pains. It was reported that in those years, about 10% of the 250 000 individuals living in Tehran were addicted to opium. Finally, the combination of the factors related to Britain, i.e., famine, opium, and the Spanish flu, and the weakness of the Qajar governments resulted in many casualties among Iranian people. Although the British troops were also infected with the virus, they depredated food, grains, and other necessities and had medical supplies. Due to these supports, they had low casualties and were safe against the Spanish flu.17-20

Conclusion

The condition of war, lack of roads between cities and villages, insecurity, stagnation of imports and exports, increasing demands for consumer goods and public food in the Iranian market, needs of Allied forces, and moving the public necessities out of the country, especially from the southern borders, caused a challenging crisis in the society and led to economic failure, outbreak of famine, diseases, and general poverty all over the country. At that time, the Spanish flu appeared in Tehran in 1918. The incident was extremely severe and catastrophic, but foreign historians such as Cyril Lloyd Elgood refused to provide any information. This was also mentioned by Willem Floor in his documents. Among the historians of Tehran’s local history, only Qahreman Mirza Salour Eyn-Saltaneh assessed this disease accurately and definitely. In the end, Britain caused the development of three factors, namely famine, opium, and the Spanish flu. These three factors along with the weakness of the Qajar government caused an increase in the number of casualties in Iran. Although the British troops were also infected with the virus, they depredated food, grains, and other necessities and had medical facilities. Hence, they did not experience many casualties.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution

SAG: idea and design of the research; SAG and MEZ: collecting of data; SAG, MEZ, FA, and MF: drafting and finalizing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved and financially supported by the Research Center for Traditional Medicine and History of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

References

- Patterson KD, Pyle GF. The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med 1991; 65(1):4-21. [ Google Scholar]

- Barclay W, Openshaw P. The 1918 influenza pandemic: one hundred years of progress, but where now?. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6(8):588-9. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30272-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Phillips H. Influenza pandemic, in: 1914-1918-online. In: Daniel U, Gatrell P, Janz O, Jones H, Jennifer Keene J, Kramer A, et al, eds. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin; 2014. p. 1-19. 10.15463/ie1418.10148.

- Stone N. World War One: A Short History. New York: Basic Books; 2009. p. 5.

- Azizi MH, Raees Jalali GA, Azizi F. A history of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic and its impact on Iran. Arch Iran Med 2010; 13(3):262-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Floor WM. Studies in the History of Medicine in Iran. Trans. Nabipour IS, Vahdat K, Nabipour IR. Bushehr: Bushehr University of Medical Sciences; 2018. p. 213-32. [Persian].

- Floor WM. Public health in Qajar Iran. Trans, Nabipour Ir. Bushehr: Bushehr University of Medical Sciences; 2007. p. 27. [Persian].

- Rhazes. Kitāb al-Hāwī fī al-tibb. Haytham Khalifa, editor. 6th ed. Beirut: Dar Ahya al-Teras al-Arabi; 2001. p. 308. [Arabian].

- Avicenna. The Canon of Medicine. 3rd ed. Beirut: Dar Ahya al-Teras al-Arabi; 2005. p. 14-6. [Arabian].

- Montasab-Majabi H. A Review of Shia Medical Texts in Medical History. Kermanshah: Razi University; 2007. p. 314. [Persian].

- Ahmadiyya A. The Secret of Treatment (A Treatise on Traditional Medicine and Herbal Medicine). 1st ed. Tehran: Eghbal; 2008. p. 3-6. [Persian].

- Ghassabi Gazkouh J, Vakili H, Rezaeian SM, Golshani SA, Salehi A. Contagious diseases and its consequences in the late Qajar period Mashhad (1892-1921). Arch Iran Med 2020; 23(6):414-21. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.37 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Farahani H. Newspaper Contemporary History of Iran. 3rd ed. Tehran: Political Studies and Research Institute; 2006. p. 454. [Persian].

- Elgood CL. Medical History of Persia and The Eastern Caliphate. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1951. p.466.

- Bagley FRC. Elgood, Cyril Lloyd. (1893-1970)”, in Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 4: 362-363.

- Eyn- Saltaneh QMSE-SRK. Roznameh Khaterat Eyn- Saltaneh. 7th ed. Edit Salour M & Afshar E. Tehran: Asateer; 1995. [Persian].

- Golshani SA, Zohalinezhad ME, Taghrir MH, Ghasempoor S, Salehi A. Spanish flu and the end of World War I in Southern Iran from 1917-1920. Arch Iran Med 2021; 24(1):78-83. doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Majd MG. The Great Famine and Genocide in Persia, 1917-1919. Tehran: Political Studies and Research Institute; 2007. p. 73-9. [Persian].

- Dehghan-Hesampour M. Opium, widespread causes of cultivation and its effects on the economy and society of Iran (1796-1926) [Thesis ]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University, Faculty of Humanities; 2012, p. 236-42. [Persian].

- Shakarami A. Drugs and Addiction. Tehran: Gutenberg Publishing; 1989. p. 48. [Persian].