Arch Iran Med. 24(11):856-857.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.127

Opinion

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation in Iran: Actions to Be Done

Fatemeh Shaygani 1, 2, *  , Mohammad Hassan Zahedroozegar 2

, Mohammad Hassan Zahedroozegar 2  , Behnam Honarvar 2

, Behnam Honarvar 2  , Mohammad Reza Shaygani 2, 3

, Mohammad Reza Shaygani 2, 3

Author information:

1Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2Health Policy Research Center, Institute of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

3Young Researchers and Elite Club, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Fatemeh Shaygani, MSc, Researcher of Health policy Research Center, Institute of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Email:

Shaygani.f@gmail.com

Copyright and License Information

© 2021 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Shaygani F, Zahedroozegar MH, Honarvar B, Shaygani MR. Eradicating female genital mutilation in iran: actions to be done. Arch Iran Med. 2021;24(11):856-857. doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.127

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined as any injury to or partially/totally removing the external genital system of young women for non-medical reasons.1 It is violence against women which is rooted in sociocultural values and beliefs of societies.2 Mostly, it is thought that FGM can reduce girls’ libido and this would prevent them from engaging in premarital sex and protect family honor.1 Also, it is believed that the removal of some parts of body which are considered unclean and masculine can make girls beautiful and clean and this would prepare girls for adulthood and improve their marriageability.1 Although it is claimed to have no religious support, there is an evidence of the practice being previously performed in some followers of different religions including Jews, Christians and Muslims.3 In Islam, it is prescribed in few Sunni hadith collections and has a number of advocates among religious leaders, as well.3 FGM is still performed in 30 countries across the world, mainly concentrated in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.4 It is estimated that the number of alive FGM victims is now over 200 million individuals globally which increases by 3 million every year.4 In Iran, FGM is performed in four provinces; Hormozgan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and West Azerbaijan which are mostly seen among Sunnis, but it is also seen among some Shiites of these areas as it becomes a local culture.5 According to the statistics in 2018, the costs of treating the health complications of FGM for 27 countries were estimated to be about 1.4 billion USD during one year which is expected to see a 150% increase by the year 2047 if no change occurs in FGM prevalence.1

Although a downward trend has been observed in the number of girls who have undergone FGM, a milestone resolution was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2012 to eliminate the issue.6 Ending harmful practices, such as FGM, was also mentioned in the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 which should be met by the year 2030.7 Both documents call for taking appropriate measures by the societies to stop this violent activity.6,7 Different steps such as banning the practice and increasing public awareness have been taken in some countries; however, there are no available statistics on performing activities against the practice in Iran.8

Authors’ Recommendations

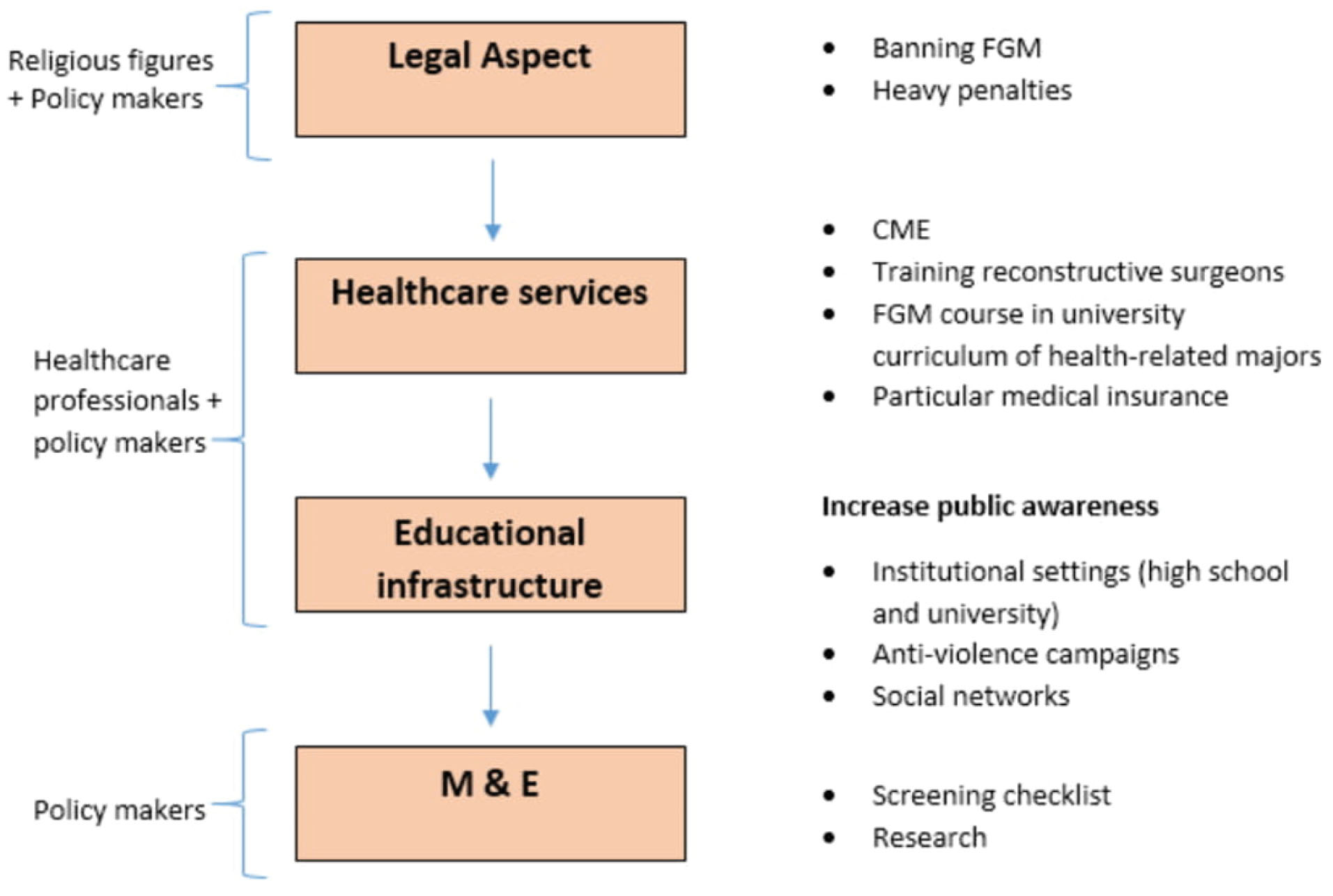

From our point of view, the process of tackling the issue in this country needs a desirable level of collaboration betweenhealth care providers, religious figures and policy makers which would be facilitated using the recommendations below. This would take about 5 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Authors’ Recommendations Flow Chart.

.

Authors’ Recommendations Flow Chart.

With strong support from national religious figures, strict laws on banning the practice must be enacted. Also, there must be heavy penalties for those health care providers performing FGM.

There must be an annual compulsory continued medical education (CME) course for all qualified healthcare providers providing them with the especial knowledge of necessary high-quality health services for FGM victims. Additionally, training reconstructive surgeons is very important and valuable. A comprehensive course about the issue must be included in the curriculum of all health-related majors at the undergraduate level. Of higher importance is provision of particular insurance covering the expenses of special healthcare and consultation services for these victims.

Moreover, providing science-based educational infrastructure plays a crucial role in changing old beliefs, whether derived from culture or religion. Regarding the issue, increasing public awareness toward the practice is highly important for terminating it, especially among people living in rural areas and slums, those with lower educational levels and more importantly, traditional and religious people, particularly the Sunnis. Primary healthcare workers and local midwives or physicians are considered as the frontline for improving people’s health knowledge. Regarding FGM, they can easily check whether or not patients or people around them have undergone such practice and give them the necessary information during healthcare checkups as most of local trust and respect them greatly, especially in rural areas. It should be taught that contrary to old notions, not only is there no health benefit in FGM, but it also leads to a variety of acute and chronic health complications for girls and women.3,9 These teachings would gradually change the way people think about the practice and help them to make the more logical decision with the correct information. Of course, the process must be supported by missionaries who have a good influence on religious people.

Furthermore, these patients can be selected as health ambassadors to inform their acquaintances’ awareness regarding the issue (peer education) which seems to be highly effective, especially in terms of many health issue whose causes are rooted in culture.

Institutional settings such as high schools and universities play a vital part in increasing girls’ and women’s awareness toward the issue; appropriate and localized scientific information should be included in the family planning course of university curricula. Also, parent-teacher meetings in girls’ schools can be an opportunity for teachers to give valuable information in order to inform students’ parents as decision makers of the practice. It is immensely important as FGM is mostly performed before the age of 15 and informing parents would act as a protective wall around the potential FGM victim.

Moreover, anti-violence campaigns of the national NGOs should be strengthened and NGOs’ educational potentials for improving public knowledge should be used by the government. It is of high importance as the educational workforce comprises young volunteers and activists seeking to help others for free and this free participation, to a large extent, reduces the financial burden of hiring educators from the government to change this sociocultural practice.

Also, popular social networks can be used in this regard which are mostly free and one of the most effective ways of informing people in the shortest possible time in today’s world. Of course the considerable impact of national TV and radio channels on providing information should not be underestimated because they have a wider range of audience in all age groups compared with social networks and they are in their own language, too.

It should be mentioned that the whole program needs a high level of support by religious leaders of the country. Having the full support of this group would prevent interference of highly religious groups of people and it would help the practice to vanish at a faster pace.

After a five-year period of legislation, an appropriate monitoring and evaluation (M & E) method must be performed to ensure that women’s right is acknowledged in this regard. It seems that applying a screening checklist to the online system of national integrated health services (SIB) is the best and most cost-effective way; it is an opportunity for informing people by expert primary healthcare workers who have taken a related course at an institutional setting (course or CME) as well as providing policy makers with a clear vision of the level of public knowledge, attitude, risk perception and practice toward the issue for further interventional programs. Finally, a comprehensive research project at the national level is highly recommended.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors have contributed to writing the draft and revising it.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None.

Ethical Statement

Not applicable.

References

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation fact sheet 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Female genital mutilation 2008. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/ippf_briefing_paper_female_genital_mutilation.pdf.

- Haji Foghaha M, Simbar M, Golezar S, Alizadeh S. Female genital mutilation: religious coercion or cultural requirement?. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil 2016; 19(25):8-16. doi: 10.22038/ijogi.2016.7785 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- United Nations International Children’s fund. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Global Concern 2016. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGMC_2016_brochure_final_UNICEF_SPREAD.pdf.

- Ahmady K. Prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) in Iran 2005-2015. J Adv Res Soc Sci Humanit 2016; 2(1):23-44. [ Google Scholar]

- United Nations. UN General Assembly Adopts Worldwide Ban on Female Genital Mutilation (New York : United Nations) 2012. Available from: http://www.npwj.org/FGM/UN-General-Assembly-Adopts-Worldwide-Ban-Female-Genital-Mutilation.html.

- United Nations. UN Substainable Development Goals: Gender Equality 2020. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/.

- World Health Organization. Violence info Islamic Republic of Iran 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/violence-info/country/IR.

- Simbar M, Abdi F, Zaheri F, Mokhtari P, Dadkhah Tehrani T, Shahoi R. Outcomes of circumcision in women: a review of existing studies. Jorjani Biomed J 2014; 2(1):1-10. [ Google Scholar]