Arch Iran Med. 24(10):747-751.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.110

Original Article

The PTRHD1 Mutation in Intellectual Disability

Sara Cheraghi 1, 2  , Sahar Moghbelinejad 3, Hossein Najmabadi 4, Kimia Kahrizi 4, Reza Najafipour 4, *

, Sahar Moghbelinejad 3, Hossein Najmabadi 4, Kimia Kahrizi 4, Reza Najafipour 4, *

Author information:

1Department of Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

2Student Research Committee, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Cellular and Molecular Research Centre, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

4Genetics Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Reza Najafipour, MD; Genetics Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran, Kodakyar Ave., Daneshjo Blvd., Evin, Post code: 1985713834, Tel: +98-21- 22180138; Email:

rnajafipour@gmail.com

Abstract

Background:

Intellectual disability (ID) is a heterogonous disorder with complex etiology. The frequency of autosomal recessive inheritance defects was elevated in a consanguineous family.

Methods:

In this study, high-throughput DNA sequencing was performed in an Iranian consanguineous family with two affected individuals to find potential causative variants. Whole-exome sequencing was carried out on the proband and Sanger sequencing was implemented for validation of the likely causative variant in the family members.

Results:

A novel homozygous missense mutation (p.Arg122Trp) was detected in the PTRHD1 gene.

Conclusion:

PTRHD1 has been recently introduced as a candidate ID and Parkinsonism causing gene. Our findings are in agreement with the clinical spectrum of PTRHD1 mutations; however, our affected individuals suffer from ID manifestations.

Keywords: Autosomal recessive intellectual disability, Consanguinity, Iran, Mutation, Whole exome sequencing

Copyright and License Information

© 2021 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Cheraghi S, Moghbelinejad S, Najmabadi H, Kahrizi K, Najafipour R. The PTRHD1 mutation in intellectual disability. Arch Iran Med. 2021;24(10):747-751. doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.110

Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID), with close to 3% prevalence, is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders.1 The important risk factor in most of Iran is consanguineous marriage2 that leads to high frequency of recessive disorders.3,4 The prevalence of ID has increased three- to five-folds in children born to first-cousin marriages.5 According to the results of some studies, autosomal recessive ID (ARID) is not rare and 13%–24% of ID cases may be caused by AR genes.2 Usually, ARID occurs by housekeeping gene mutations such as protein degradation, metabolism, DNA transcription and translation and cell division genes.6

ID and developmental delay (DD) is a heterogonous disorder with complex etiology. Whole exome sequencing (WES) facilitates the diagnosis of affected individuals with no diagnosis.7 Here, we report WES in a consanguineous family with two ID/DD affected individuals. In this study, we identified a homozygous mutation in the peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase domain containing 1 (PTRHD1) gene in the patients. In two previous independent studies, a homozygous missense mutation in PTH2 domain (p.Cys52Tyr, p.His53Tyr) of PTRHD1 has been reported in two Iranian families with ID and Parkinsonism.8,9 Also, homozygous frameshift in the PTH2 domain (p.Ala57Argfs*26) has been recently identified in a South African family with ID and juvenile-onset Parkinsonism.10 However, in our study, the PTRHD1 variant was identified in individuals with ID/DD with first-cousin parents and without clinical symptoms of Parkinsonism. Iran has a high frequency of relative marriage (approximately 40%).11,12 Our molecular investigation highlighted the autosomal recessive of ID as the genetic cause in this family.

Materials and Methods

Patients

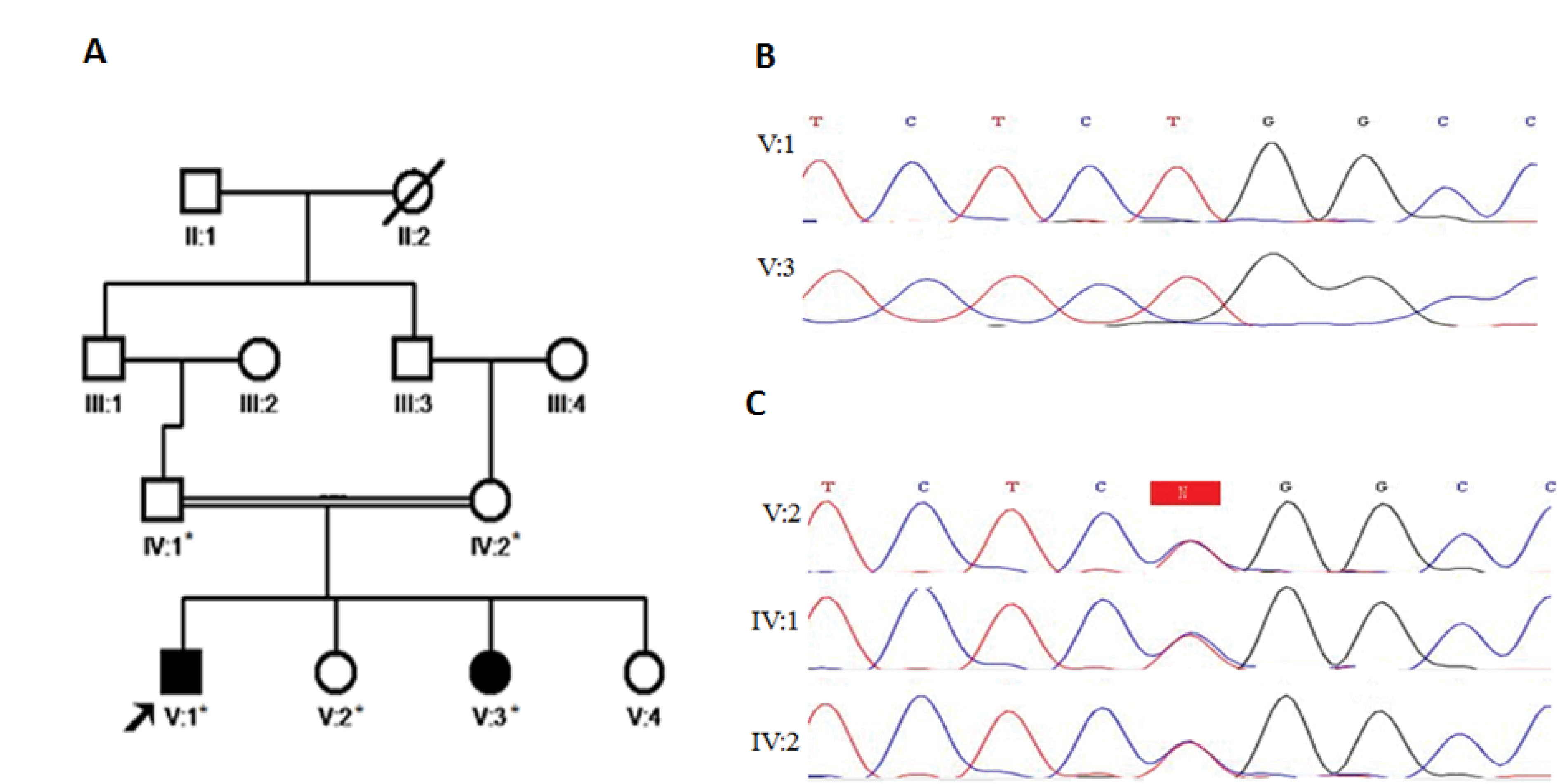

The study was performed on two siblings affected with ID/DD from healthy first-cousin parents (Figure 1A) originating from central Iran (Qazvin province). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Genetic Research Center (GRC) at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Informed consent was obtained from parents, and patients had been screened for fragile X syndrome.

Figure 1.

A) Pedigree of healthy first cousin parent with two ID affected patients. B) Homozygous mutant (c.364C>T) is shown by Sanger sequencing chromatograms in patient (V:1 and V:3). C) Sanger sequencing chromatograms show heterozygous carriers of the mutation in the parent and a healthy sister (IV:1, IV:2 and V:2).

.

A) Pedigree of healthy first cousin parent with two ID affected patients. B) Homozygous mutant (c.364C>T) is shown by Sanger sequencing chromatograms in patient (V:1 and V:3). C) Sanger sequencing chromatograms show heterozygous carriers of the mutation in the parent and a healthy sister (IV:1, IV:2 and V:2).

Patient V:1

The proband is an 18-year-old male, who was born full-term with a birth weight of 3400 g (-0.26 SD), occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) of 35 cm (-0.40 SD) and length of 53 cm (+1.08 SD). He had psychomotor and speech delay. Seizure started at the age of 9 months and is being controlled by aripiprazole and MemoPlus. On examination (18 years old), his OFC was 58 cm (+2.02 SD), height was 178 cm (+0.43 SD), and weight was 100 kg (+2.20 SD). The patient was characterized by moderate ID, learning disability, self-talking but no evidence of tremor gait disturbances, psychiatric phenotypes and postural instability. There was no family history of mental retardation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Features in Patients with PTRHD1 Variants

|

Clinical Features

|

Clinical Manifestations in Individuals with Homozygous

PTRHD1

Mutation

|

|

This Study (n=2)

|

Jaberi et al, 2016 (n=2)

|

Khodadadi et al, 2017 (n=2)

|

Kuipers et al, 2018 (n=3)

|

| Gender |

F/M |

M |

M |

F |

| Origin |

Iranian |

South African (Xhosa) |

| Parkinsonism |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Intellectual disability |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Developmental delay |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Learning disability |

+ |

nm |

+/- |

+/- |

| Seizure |

+/- |

+/- |

nm |

+/- |

| Abnormal behavior |

+ |

+/- |

- |

nm |

|

PTRHD1 variant |

p.Arg122Trp |

p.Cys52Tyr |

p.His53Tyr |

p.Ala57Argfs*26 |

| Zygosity |

HOM |

HOM |

HOM |

HOM |

n, Number; F, Female; M, Male; nm, not mentioned; HOM, Homozygous.

Patient V:3

The second patient of the family was an 11-year-old female born full-term with an unremarkable pregnancy and neonatal period. Neonatal birth weight was 3400 g (-0.05 SD), OFC was 35 cm (+0.11 SD) and length was 53 cm (+1.29 SD). She had a slight psychomotor and speech delay. On examination (11 years old), her OFC was 56 cm (+2.46 SD), height was 156 cm (+1.64 SD), and weight was 40 kg (+0.25 SD). She had moderate ID, hyperactivity, self-talking, aggressive behavior and learning disability; she never developed tremor gait disturbances, psychiatric phenotypes and postural instability (Table 1).

Whole Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood sample of the patients and close members of the family using the salting out protocol.13 WES was performed for patient V:1 (Figure 1A). Exome capture and prepare library were executed using the Agilent SureSelectXT2 kit (Version 6) (Agilent Technologies, Lake forest, CA, USA). The Illumina NextSeq 500 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) provided paired-ends sequencing. WES analysis was carried out according to previous publication6; briefly, the sequencing quality was detected by FastQC 11.5 software.14 Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA) version 0.7.12-r1039 was used to align the row reads with reference genome (GRCh37/hg19); variant calling and annotation were then implemented using GATK toolkit version 3.6 and Annovar32, respectively. Variant filtering was performed by exclusion of all non-coding regions and synonymous variants. At first, the known ID/DD-causing genes were considered.6,15 Variant prioritization was categorized by mineral allele frequency ≤5% in population-scale resources such as 1000 Genome project,16 genomAD, ExAC Browser17 and ESP6500,18 prediction scores (CADD, SIFT, MutationTaster, PolyPhen2, and PROVEAN), and conservation scores (GERP++ and SiPhy).19 Potential diseases-causing variants ACMG criteria were determined by InterVar.20 All candidate variants were validated in patients by Sanger sequencing and cosegregation analysis was performed in the healthy family members.

Results

WES was reached with the mean depth of coverage 57X with 95.4% and 91.9% coverage at 10X and 20X, respectively. A novel missense mutation, NM_001013663: c.364C>T; p.Arg122Trp was identified in the PTRHD1 gene with autosomal recessive inheritance. Of note, no potential causative homozygous and compound heterozygous/homozygous variants of known disease genes were identified. Nonetheless, the homozygous mutation in PTRHD1 was detected by an exome-wide analysis of V:1 individual. Sanger sequencing in the affected siblings confirmed the homozygous potential causative allele and also heterozygous status of the variant region was detected in the healthy family members (Figures 1B and C).

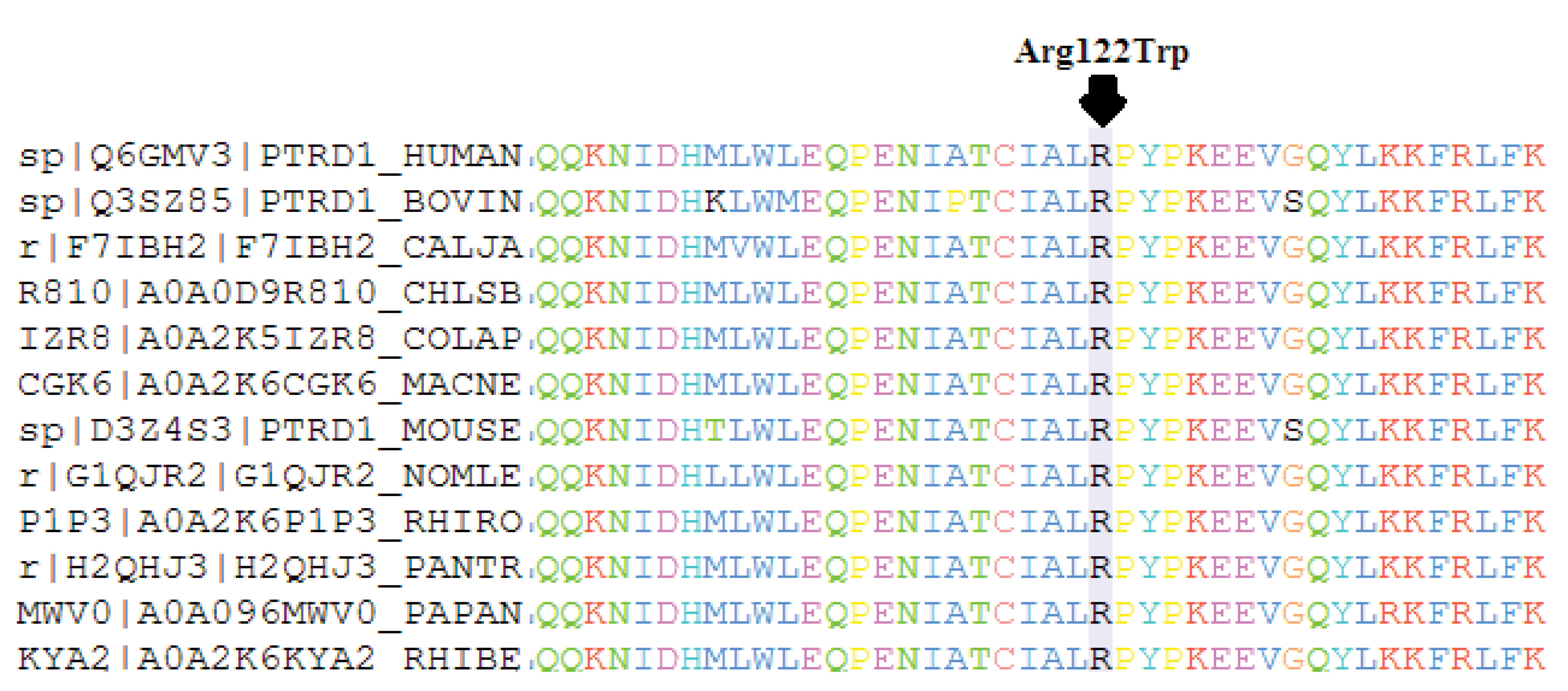

The variant is not present in different population resources (1000 Genome Project, ExAc, ESP, genomAD and our in-house database (Iranian database: http://www.iranome.com) or in Clinvar and HGMD databases. More than five in silico prediction tools have revealed the variant to be disease-causing (Table 2). Multiple sequence alignment was widely conserved across species (Figure 2).

Table 2.

In Silico Analysis Tools Used for the PTRHD1 Mutation (p.Arg122Trp) Pathogenicity Prediction

|

Tools

|

Prediction Value

|

| CADD |

29.2 |

| SIFT |

0.001 |

| Polyphen2 |

1 |

| LRT |

0 (D) |

| MutationTaster |

0.999 |

| PROVEAN |

-6 |

| DANN |

0.999 |

| Fathmm-MKL_coding |

0.647 |

A variant is considered to be damaging and deleterious if the predicted values are as follows: CADD: higher values are more deleterious, SIFT > 0.05 (damaging), Polyphen > 0.8 (probably damaging), LRT;D: Deleterious, Mutation Taster > 0.5 (disease-causing), Provean > − 2.5 (deleterious), DANN: higher values are more deleterious, Fathmm-MKL_coding ≥ 0.5 (deleterious).

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment shows the region (highlighted residue) which is conserved across species.

.

Multiple sequence alignment shows the region (highlighted residue) which is conserved across species.

Discussion

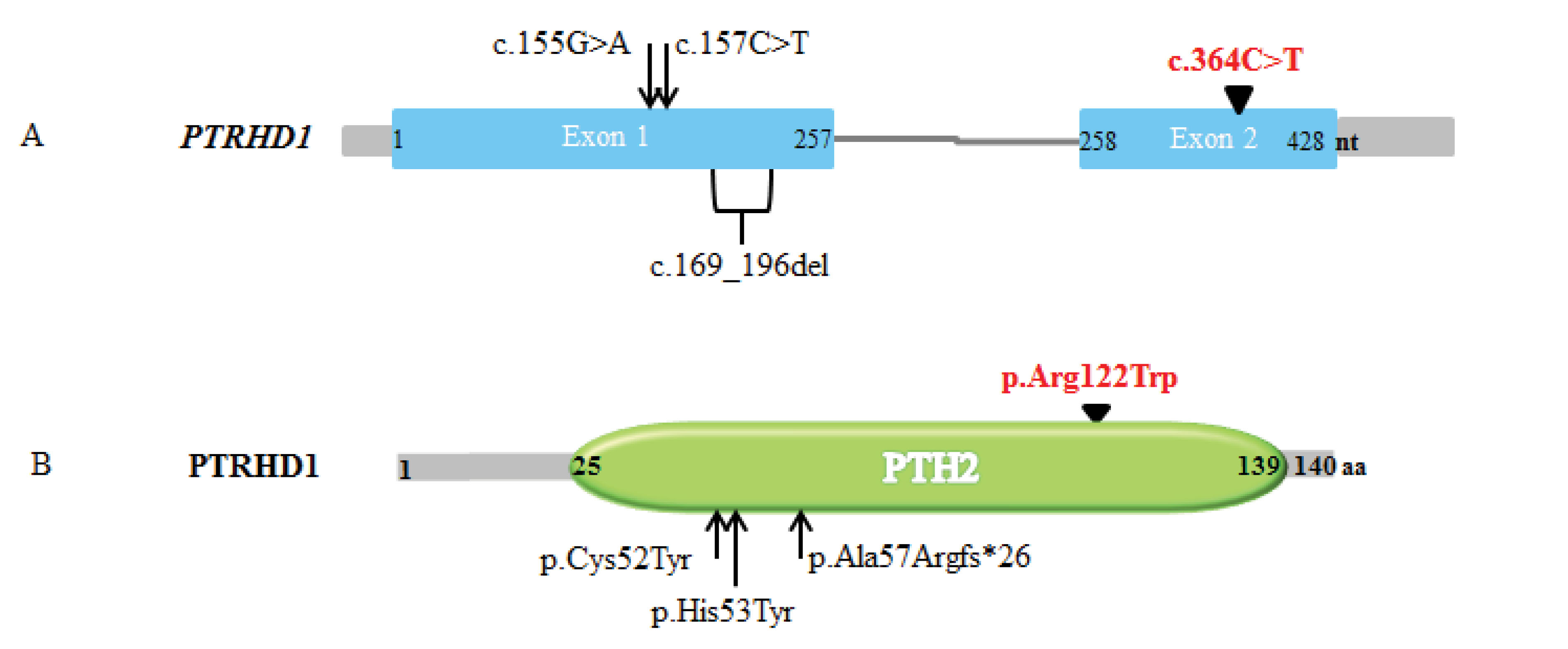

Here, we report a novel autosomal recessive variant in the C-terminal of the PTH2 domain (located in 25-139 residue positions) of the PTRHD1 gene (C2orf79) in an Iranian consanguineous family with ID. The conserved C-terminal of the PTH2 domain has a role in catalytic activity, the active site region is amino acids 72 to end residues.21 Variants in PTRHD1 were recently reported in three studies as combined phenotypes of ID and Parkinsonism, but in this study, we found a PTRHD1 variant in two siblings with ID and without any parkinsonism manifestations (Figure 3). For the first time, in an Iranian related family, Jaberi et al detected a homozygous missense variant in PTRHD1 (p.Cys52Tyr) in two male siblings with early-onset Parkinsonism and healthy parents. They also found a homozygous variant in ADORA1 to mention the stronger disease potential causative variant. Rest and jaw tremor, postural instability, psychomotor retardation, bradykinesia and mental retardation features in the younger affected manifested in their patients.8 Early after the first report, Khodadadi et al identified a homozygous missense mutation (p.His53Tyr) in two Iranian male siblings with the same features such as movement disorder, muscle stiffness, postural instability, rest and postural tremor, speech disorder, gait disturbances, psychiatric phenotypes and mild ID phenotypes. The PTRHD1 gene was suggested as the novel causative gene for combined clinical features of Parkinsonism and ID.9 In the investigation by Kuipers et al, a homozygous frameshift variant in the PTRHD1 (p.Ala57Argfs*26) was detected in three affected individuals with juvenile-onset Parkinsonism and ID in a South African Xhosa family (Table 1).10

Figure 3.

A)Schematic PTRHD1 gene representation. The c.364C>T variant within exon 2 (in red) in this study displaying to compare with the other three previous variants (within exon 1).

10

B) Schematic structure of PTRHD1 protein and variants that reported in neurodegenerative disease until now. Three variant locations in previous studies identified in N-terminal of PTH2 domain are presenting to compare with the C-terminal p.Arg122Trp variant (in red) in our finding.

.

A)Schematic PTRHD1 gene representation. The c.364C>T variant within exon 2 (in red) in this study displaying to compare with the other three previous variants (within exon 1).

10

B) Schematic structure of PTRHD1 protein and variants that reported in neurodegenerative disease until now. Three variant locations in previous studies identified in N-terminal of PTH2 domain are presenting to compare with the C-terminal p.Arg122Trp variant (in red) in our finding.

PTRHD1 has a ubiquitous activity that involves indirectly in ubiquitin proteasome pathway by the ubiquitin-like (UBL) protein, the PTH2 (peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase 2) domain is a UBL binding protein.22 PTRHD1 was first mentioned as a peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase; however, peptidyl-tRNA was not cleaved in functional study, but in yeast PTH activity is independent of its ubiquitin proteasome pathway.23 The UBL acts as a shuttle protein in ubiquitin proteasome systems (UPS) that binds to Rad23 and Dsk2 to link ubiquitinated substrates, as well as Rad23 and Dsk2 acting as guides to bear UBL-substrates to the proteasome.24 Rad23 and Dsk2 are ubiquitin like-ubiquitin associated (UBL-UBA) proteins which interact with C-terminal of the PTH2 domain.22 Protein turnovers were provided by UPS whose dysfunction is well-known in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders such as ID.25,26 Neurogenesis, neurite formation, neuronal migration and synapse function are affected by the UPS which reveals its involvement in neurodevelopmental disorders.27

In conclusion, in line with previous studies in ID families with consanguineous marriage, our study also confirms the elevation of the incidence of homozygous ID risks. In addition, with our genetic finding, further evidence is provided for ID-causing by PTRHD1. The novel homozygous variant in our study probably affects substrate binding to the PTH2 active site. Functional analysis could confirm the pathogenicity of the gene in ID/DD.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients’ family for their patience and cooperation.

Authors’ Contribution

SCh involved in analysis and interpretation of data, HN, KK and RN collaborated in conception and design of study, SM and SCh helped in proposal approval process and data collection, all authors reviewed and approved the final draft of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was supported by the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) with grant no. 950022 to HN, and grant no. 96011200 to KK, and National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) with grant no. 957060 to KK and grant no. 958715 to HN.

References

- Kaufman L, Ayub M, Vincent JB. The genetic basis of non-syndromic intellectual disability: a review. J Neurodev Disord 2010; 2(4):182-209. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9055-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Musante L, Ropers HH. Genetics of recessive cognitive disorders. Trends Genet 2014; 30(1):32-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bundey S, Alam H. A five-year prospective study of the health of children in different ethnic groups, with particular reference to the effect of inbreeding. Eur J Hum Genet 1993; 1(3):206-19. doi: 10.1159/000472414 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Modell B, Darr A. Science and society: genetic counselling and customary consanguineous marriage. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3(3):225-9. doi: 10.1038/nrg754 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kahrizi K, Hu H, Hosseini M, Kalscheuer VM, Fattahi Z, Beheshtian M. Effect of inbreeding on intellectual disability revisited by trio sequencing. Clin Genet 2019; 95(1):151-9. doi: 10.1111/cge.13463 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Kahrizi K, Musante L, Fattahi Z, Herwig R, Hosseini M. Genetics of intellectual disability in consanguineous families. Mol Psychiatry 2019; 24(7):1027-39. doi: 10.1038/s41380-017-0012-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Qiu W, Ji X, Liu X, Huang Z, Liu H. Marked yield of re-evaluating phenotype and exome/target sequencing data in 33 individuals with intellectual disabilities. Am J Med Genet A 2018; 176(1):107-15. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38542 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jaberi E, Rohani M, Shahidi GA, Nafissi S, Arefian E, Soleimani M. Mutation in ADORA1 identified as likely cause of early-onset parkinsonism and cognitive dysfunction. Mov Disord 2016; 31(7):1004-11. doi: 10.1002/mds.26627 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi H, Azcona LJ, Aghamollaii V, Omrani MD, Garshasbi M, Taghavi S. PTRHD1 (C2orf79) mutations lead to autosomal-recessive intellectual disability and parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2017; 32(2):287-91. doi: 10.1002/mds.26824 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kuipers DJS, Carr J, Bardien S, Thomas P, Sebate B, Breedveld GJ. PTRHD1 Loss-of-function mutation in an african family with juvenile-onset parkinsonism and intellectual disability. Mov Disord 2018; 33(11):1814-9. doi: 10.1002/mds.27501 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kuss AW, Garshasbi M, Kahrizi K, Tzschach A, Behjati F, Darvish H. Autosomal recessive mental retardation: homozygosity mapping identifies 27 single linkage intervals, at least 14 novel loci and several mutation hotspots. Hum Genet 2011; 129(2):141-8. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0907-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Saadat M, Ansari-Lari M, Farhud DD. Short report consanguineous marriage in Iran. Ann Hum Biol 2004; 31(2):263-9. doi: 10.1080/03014460310001652211 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16(3):1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. Available from: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc.

- Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature 2011; 478(7367):57-63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015; 526(7571):68-74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016; 536(7616):285-91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fu W, O’Connor TD, Jun G, Kang HM, Abecasis G, Leal SM. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature 2013; 493(7431):216-20. doi: 10.1038/nature11690 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Lassmann T. A phenotype centric benchmark of variant prioritisation tools. NPJ Genom Med 2018; 3:5. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0044-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang K. InterVar: clinical interpretation of genetic variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP guidelines. Am J Hum Genet 2017; 100(2):267-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- De Pereda JM, Waas WF, Jan Y, Ruoslahti E, Schimmel P, Pascual J. Crystal structure of a human peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase reveals a new fold and suggests basis for a bifunctional activity. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(9):8111-5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311449200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Funakoshi M, Kobayashi H. Yeast Pth2 is a UBL domain-binding protein that participates in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J 2006; 25(23):5492-503. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601418 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Burks GL, McFeeters H, McFeeters RL. Expression, purification, and buffer solubility optimization of the putative human peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase PTRHD1. Protein Expr Purif 2016; 126:49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.05.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Oania R, Graumann J, Deshaies RJ. Multiubiquitin chain receptors define a layer of substrate selectivity in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell 2004; 118(1):99-110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Fang K, Zhang K, Wang J. Network-based analysis of schizophrenia genome-wide association data to detect the joint functional association signals. PLoS One 2015; 10(7):e0133404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133404 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheon S, Dean M, Chahrour M. The ubiquitin proteasome pathway in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2019; 165:106791. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.01.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hegde AN, Upadhya SC. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in health and disease of the nervous system. Trends Neurosci 2007; 30(11):587-95. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]