Arch Iran Med. 24(12):887-896.

doi: 10.34172/aim.2021.133

Original Article

The Spectrum of Pathogenic Variants in Iranian Families with Hemophilia A

Sarah Azadmehr 1  , Faezeh Rahiminejad 1, Fatemeh Zafarghandi Motlagh 1, Mojdeh Jamali 1, Pardis Ghazizadeh Tehrani 1, Tina Shirzadeh 1, Hamideh Bagherian 1, Morteza Karimipoor 2, Elham Davoudi-Dehaghani 2, *

, Faezeh Rahiminejad 1, Fatemeh Zafarghandi Motlagh 1, Mojdeh Jamali 1, Pardis Ghazizadeh Tehrani 1, Tina Shirzadeh 1, Hamideh Bagherian 1, Morteza Karimipoor 2, Elham Davoudi-Dehaghani 2, *  , Sirous Zeinali 1, 2, *

, Sirous Zeinali 1, 2, *

Author information:

1Medical Genetics Lab of Dr. Zeinali, Kawsar Human Genetics Research Center, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Molecular Medicine, Biotechnology Research Center, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran, Iran

*Corresponding Authors: Sirous Zeinali, PhD; Medical Genetics Lab of Dr. Zeinali, Kawsar Human Genetics Research Center. No. 41 Majlesi St., Valiasr St., Tehran,

Iran. Tel:+98-912-1372040; Fax:+98-21-88939140; Email:

zeinali@gmail.com; Elham Davoudi-Dehaghani, PhD; Department of Molecular Medicine, Biotech-c

nology Research Center, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Pasteur St., Tehran, Iran. Tel:+98-917-1103682; Fax:+98-21-64112535; Email:

davoodie419419@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background:

Hemophilia A (HA) is an X-linked recessive bleeding disorder with a high rate of genetic heterogeneity. The present study was conducted on a large cohort of Iranian HA patients and data obtained from databases.

Methods:

A total of 622 Iranian HA patients from 329 unrelated families who had been referred to a medical genetics laboratory in Tehran from 2005 to 2019, were enrolled in this retrospective, observational study. Genetic screening of pathogenic variants of the F8 gene was performed using inverse shifting PCR, direct sequencing, and multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (MLPA). Point mutation frequencies in different exons were analyzed for our samples as well as 6031 HA patients whose data were recorded in a database.

Results:

A total of 144 different pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants including 29 novel variants were identified. A strategy to decrease costs of genetic testing of HA was suggested based on this finding.

Conclusion:

This study provides comprehensive information on F8 pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in Iranian HA patients which improves the spectrum of causative mutations and can be helpful to clinicians and medical geneticists in counseling and molecular diagnosis of HA.

Keywords: Genetic test, Hemophilia A, Point mutation, Prenatal diagnosis

Copyright and License Information

© 2021 The Author(s).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Azadmehr S, Rahiminejad F, Zafarghandi Motlagh F, Jamali M, Ghazizadeh Tehrani P, Shirzadeh T, et al. The spectrum of pathogenic variants in iranian families with hemophilia A. Arch Iran Med. 2021;24(12):887-896. doi: 10.34172/ aim.2021.133

Introduction

Hemophilia A (HA, OMIM: 306 700) is an X-linked hereditary bleeding disorder with an incidence of 1: 5000 male births. HA is caused by a deficiency in coagulation factor VIII clotting activity; according to the baseline activity of this factor, HA is classified as severe (< 1%), moderate (1–5%) or mild (> 5%).1 The FVIII is a plasma glycoprotein that participates in the blood coagulation cascade as a cofactor of factor IX (FIX) serine protease. This protein has a domain structure of A1-A2-B-A3-C1-C2 encoded by the F8 gene (F8, OMIM: 300 841). The F8 gene contains 26 exons, spanning 186 kb at the Xq28 region.2,3

HA is genetically heterogeneous. So far, more than 3000 pathogenic variants have been reported, including missense, nonsense, splice-site mutations, small insertion and/or deletions, as well as large rearrangements (f8-db.eahad.org). The most common pathogenic variants associated with severe HA are intron 22 inversion (40% to 50%) and intron 1 inversion (2% to 5%). Nearly all other pathogenic variants are rare and usually confined to a single-family.4-7

Despite the advances in treating HA and increasing life expectancy, there are still challenges in management, most notably the development of inhibitors in a significant proportion of patients. Previous studies have shown that inhibitor development depends on multiple variables including genetic factors. According to the genetic studies on this disease, the type of F8 mutation is correlated to the severity of the disease and predicts the risk of inhibitor development. On the other hand, despite the recent advances in HA gene therapy, the high cost of the treatment and lack of access to these techniques in all countries has made prenatal diagnosis (PND) and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis for HA still widely used in the prevention of birth defects. These issues show the importance of the genetic study on HA patients.4-8

Iran is a country in the Middle East with a population of more than 80 million; where the prevalence of hemophilia is approximately 14 per 100 000. Although several studies have already been done on the molecular defects causing HA, there is still no comprehensive information about the molecular genetics of HA in Iran.9-13

This study was conducted to detect the spectrum of mutations in F8 gene in Iranian HA patients in more details and also to find an algorithm for reducing the cost of point mutation detection as well as a speedy process.

Patients and Methods

A total of 622 Iranian patients from 329 unrelated families with clinical and laboratory presentation of severe, moderate and mild HA, aged between 1 and 73 years, who had been referred to Dr. Zeinali’s Medical Genetics Lab, Kawsar Human Genetics Research Center, were enrolled in a retrospective observational study between 2005 and 2019. Clinical history and pedigree data were taken and written informed consent form was obtained from patients or their parents. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kawsar Human Genetics Research Center.

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood by the standard salting-out method.14 Screening for intron 22 inversion (Inv22) and intron 1 inversion (Inv1) was done using two separate inverse shifting PCRs.15,16 For point mutation detection, PCR amplification and direct sequencing of all 26 exons, exon-intron boundaries and promoter regions of the F8 gene were carried out. Sequences of primers are available upon request. The data were analyzed against reference sequence NG_011403. Finally, multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (MLPA) (P178-B2 F8 kit, MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was used for identification of deletion/duplication.

HGMD (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php), ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), VarSome (https://varsome.com), dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp), EAHAD F8 database (https://f8-db.eahad.org/), and CHAMP (CDC Haemophilia A Mutation Project, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hemophilia/champs.html) were used as a filter to identify all previously described pathogenic variants.4,17-20 In silico analysis of pathogenicity of novel variants was performed using SIFT (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/), PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2), Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), and CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/).21-24 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines were used for interpretation of identified sequence variants.25

Parental origin of pathogenic variants was determined by genotyping two RFLP markers (BCL1 and IVS7), a VNTR (DXS52) and 6 STR linked to the F8 gene (GTHapScreen®F8, Genetek Biopharma, Berlin, Germany, GT).8,26 Based on the cause of family referral to the genetic laboratory, access to family members, and informative genetic markers, the origin of the mutation was determined for 54 families (30 families with point mutations and 24 families with genomic rearrangements).

Point mutation frequencies in different exons were analyzed for our samples as well as 6031 HA patients (including 3235, 2361, 299 and 136 patients from North America, Western Europe, East Asia, and Iran, respectively) whose data were retrieved from EAHAD F8 database (https://f8-db.eahad.org/). The data obtained from this study were not pooled with those reported from Iran in the EAHAD F8 database due to the possibility of overlap between these samples.

Results

Among the 329 unrelated families, 262 (79.6%), 42 (12.7%), and 18 (5.5 %) were classified as severe, moderate, and mild, respectively. In seven (2.1%) cases, the clinical data was not available. All patients except two Turner cases and two females, offspring of consanguineous parents, were male.

Following the molecular study, F8 pathogenic variants were identified in 324 families, representing a detection rate of 98.5%. All 144 identified pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants; their locations, the severity of the disease associated with each variant, and the patients’ inhibitor status are listed in Table 1. Moreover, 17 benign/likely benign/uncertain significance variants that were identified in patients who also had another pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant are also listed in Table 2. For the severe form, the detection rate was 99.2%. After inv22 (41.6%) and inv1 mutations (1.9%), the majority of variants in the severe form were insertion and/or deletions (24.0%) followed by nonsense (12.6%), missense (9.9%), large deletion/insertion (5.3%), and splice site (3.8%). For the moderate form, with a detection rate of 92.8%, the order was missense (69.0%), small insertion and/or deletion (14.3%), nonsense (4.7%), large insertion and/or deletion (2.4%) and splice site (2.4%). As expected in the mild form, only missense mutations were identified.

Table 1.

List of Pathogenic/likely Pathogenic Variants Identified in this Study

Nucleotide Change

(NM_000132.3)

|

Amino Acid Change

(NP_000123.1)

|

Exon/

Intron

|

Domain

|

Number of Patients

|

Phenotype

|

Inhibitor

|

|

Missense

|

| c.77T > C |

p.Leu26Pro |

Ex 1 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.341C > T |

p.Pro114Leu |

Ex 3 |

A1 |

1 |

Mi |

N |

| c.517C > G, c.1372C > T |

p.Leu173Val, p.Arg458Cys |

Ex 4/9 |

A1/A2 |

1 |

Mi |

N |

| c.791T > G |

p.Leu264Arg |

Ex 7 |

A1 |

2 |

S/Mi |

— |

| c.797G > A |

p.Gly266Glu |

Ex 7 |

A1 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.832G > A |

p.Gly278Arg |

Ex 7 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.863T > C |

p.Ile288Thr |

Ex 7 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.901C > T |

p.Arg301Cys |

Ex 7 |

A1 |

2 |

S |

— |

| c.1172G > C |

p.Arg391Pro |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.1315G > A |

p.Gly439Ser |

Ex 9 |

A2 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.1487C > G |

p.Pro496Arg |

Ex 10 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1492G > A |

p.Gly498Arg |

Ex 10 |

A2 |

1 |

Mo |

N |

| c.1630G > A |

p.Asp544Asn |

Ex 11 |

A2 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.1683T > A |

p.Asp561Glu |

Ex 11 |

A2 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.1696C > T |

p.Leu566Phe |

Ex 11 |

A2 |

4/2 |

Mo/S |

— |

| c.1778T > A |

p.Ile593Asn |

Ex 12 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1834C > T |

p.Arg612Cys |

Ex 12 |

A2 |

3 |

Mi |

N |

| c.1893C > G |

p.Asn631Lys |

Ex 12 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1898T > C |

p.Met633Thr |

Ex 12 |

A2 |

1 |

Mi |

— |

| c.1952A > C |

p.His651Pro |

Ex 13 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.2013C > G |

p.Phe671Leu |

Ex 13 |

A2 |

2 |

Mi |

N |

| c.2077T > C |

p.Ser693Pro |

Ex 13 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.5122C > T |

p.Arg1708Cys |

Ex 14 |

A3 |

2 |

S/Mo |

N |

| c.5329C > T |

p.Leu1777Phe |

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

Mi |

— |

|

c.5359G>A

|

p.Glu1787Lys

|

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.5526G > A |

p.Met1842Ile |

Ex 16 |

A3 |

1 |

Mi |

— |

|

c.5558C>A

|

p.Ala1853Asp

|

Ex 16 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5641A > C |

p.Thr1881Pro |

Ex 17 |

A3 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

|

c.5724G>T

|

p.Trp1908Cys

|

Ex 17 |

A3 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.5954G > A |

p.Arg1985Gln |

Ex 18 |

A3 |

1 |

Mi |

— |

| c.6046C > T |

p.Arg2016Trp |

Ex 19 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.6319G>C

|

p.Gly2107Arg

|

Ex 22 |

C1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6443A > G |

p.Asn2148Ser |

Ex 23 |

C1 |

1 |

Mi |

— |

| c.6506G > A |

p.Arg2169His |

Ex 23 |

C1 |

3 |

Mo |

N |

| c.6539C > A, c.6541C > T |

p.Thr2180Asn, p.Leu2181Phe |

Ex 23 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6545G > A |

p.Arg2182His |

Ex 23 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.6671C > T |

p.Pro2224Leu |

Ex 24 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.6683G > A |

p.Arg2228Gln |

Ex 24 |

C2 |

3 |

S |

N |

| c.6689A > C |

p.His2230Pro |

Ex 24 |

C2 |

2 |

Mo |

N |

|

c.6844T>C

|

p.Ser2282Pro

|

Ex 25 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6967C > T |

p.Arg2323Cys |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.6968G > T |

p.Arg2323Leu |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6977G > A |

p.Arg2326Gln |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

9/5 |

Mo/Mi |

N |

| c.6989A > C |

p.Gln2330Pro |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Nonsense

|

| c.43C > T |

p.Arg15Ter |

Ex 1 |

A1 |

1 |

Unknown |

— |

|

c.801C>A

|

p.Cys267Ter

|

Ex 7 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1057C > T |

p.Gln353Ter |

Ex 8 |

a1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1063C > T |

p.Arg355Ter |

Ex 8 |

a1 |

2 |

S |

N |

| c.1165C > T |

p.Gln389Ter |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

2 |

S |

— |

| c.1236G > A |

p.Trp412Ter |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1250T > G |

p.Leu417Ter |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1336C > T |

p.Arg446Ter |

Ex 9 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1596G > A |

p.Trp532Ter |

Ex 11 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1804C > T |

p.Arg602Ter |

Ex 12 |

A2 |

2 |

S/Mo |

P |

| c.2120G > A |

p.Trp707Ter |

Ex 14 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.2440C > T |

p.Arg814Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

3/1 |

S/Mo |

P/ N |

| c.3077C > G |

p.Ser1026Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.3175A > T |

p.Lys1059Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.3381G > A |

p.Trp1127Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.4819G > T |

p.Glu1607Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.4924G > T |

p.Glu1642Ter |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5143C > T |

p.Arg1715Ter |

Ex 14 |

A3 |

2 |

S |

— |

| c.5263C > T |

p.Gln1755Ter |

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5953C > T |

p.Arg1985Ter |

Ex 18 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

P |

| c.5985C > G |

p.Tyr1995Ter |

Ex 18 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6267G > A |

p.Trp2089Ter |

Ex 21 |

C1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6403C > T |

p.Arg2135Ter |

Ex 22 |

C1 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.6496C > T |

p.Arg2166Ter |

Ex 23 |

C1 |

3 |

S |

N |

| c.6976C > T |

p.Arg2326Ter |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

2 |

S |

— |

| c.6988C > T |

p.Gln2330Ter |

Ex 26 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

N |

|

Splice-site

|

|

c.143+3_143+4insT

|

— |

Int 1 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.266-1G > A |

— |

Int 2 |

|

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1009 + 1G > A |

— |

Int 7 |

|

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.1752+5dupG

|

— |

Int 11 |

|

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1903 + 5 G > A |

— |

Int 12 |

|

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.5816-1G > A |

— |

Int17 |

|

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5998 + 1G > A |

— |

Int 18 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6115 + 4 A > G |

— |

Int 19 |

|

1 |

S |

N |

| c.6274-8A > G |

— |

Int 21 |

|

1 |

S |

N |

| c.6273 + 1G > T |

— |

Int 21 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.6430-1G > C |

— |

Int 22 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Small insertion and/or deletion

|

| c.199_200delAA |

p.Lys67AspfsTer15 |

Ex 2 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.205_206delCT |

p.Leu69ValfsTer13 |

Ex 2 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.209_212delTTGT |

p.Phe70Ter |

Ex 2 |

A1 |

4 |

S |

N |

|

c.438delA

|

p.Val147SerfsTer14

|

Ex 4 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.636delC |

p.His212GlnfsTer24 |

Ex 5 |

A1 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.1090delG |

p.Asp364ThrfsTer54 |

Ex 8 |

a1 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1184dupA |

p.Lys396GlufsTer4 |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.1230_1232del |

p.Glu410del |

Ex 8 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.1664delT

|

p.Phe555SerfsTer8

|

Ex 11 |

A2 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.2015_2017del |

p.Phe672del |

Ex 13 |

A2 |

3 |

S |

N |

| c.2354_2355del |

p.Ile785ArgfsTer4 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.2438_2448del

|

p.Leu813SerfsTer10

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.2444dupA |

p.Ser816GlufsTer11 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.2638dupG

|

p.Glu880GlyfsTer15

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

N |

|

c.2831dupA

|

p.Ser945ValfsTer6

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.2882delA

|

p.Asn961IlefsTer7

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.2945dupA |

p.Asn982LysfsTer9 |

Ex 14 |

B |

3 |

S |

N |

|

c.3242delA

|

p.Asn1081IlefsTer57

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.3275dupA |

p.Asn1092LysfsTer26 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.3409_3410del |

p.Leu1137GlufsTer28 |

Ex 14 |

B |

2 |

S |

N |

|

c.3455delG

|

p.Gly1152AspfsTer19

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.3637delA |

p.Ile1213PhefsTer5 |

Ex 14 |

B |

6/1 |

S/Mo |

P/ N |

| c.3637dupA |

p.Ile1213AsnfsTer28 |

Ex 14 |

B |

3/1 |

S/Mo |

N |

| c.3702_3705del |

p.His1234GlnfsTer2 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.3863dupC |

p.Gly1291ArgfsTer29 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.3870dupA |

p.Gly1291ArgfsTer29 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.4247delC

|

p.Pro1416HisfsTer8

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.4333delT

|

p.Ser1445LeufsTer20

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.4346_4352del |

p.Glu1449ValfsTer14 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.4379delA |

p.Asn1460IlefsTer5 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.4379dupA |

p.Asn1460LysfsTer2 |

Ex 14 |

B |

5 |

S |

P/ N |

|

c.4646_4647delAG

|

p.Glu1549GlyfsTer4

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.4686delA |

p.Val1563PhefsTer4 |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

U |

— |

|

c.4724delA

|

p.Lys1575ArgfsTer46

|

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.4770_4819delins491

|

— |

Ex 14 |

B |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.4825dupA |

p.Thr1609AsnfsTer4 |

Ex 14 |

B |

4 |

S |

N |

|

c.5296_5302delTTATACC

|

p.Leu1766ValfsTer4

|

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5350delG |

p.Ala1784GlnfsTer9 |

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.5366_5368delATA

|

p.Asn1789del

|

Ex 15 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

N |

| c.5387delA |

p.Asn1796IlefsTer75 |

Ex 16 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5674delG |

p.Val1892TyrfsTer53 |

Ex 17 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

— |

| c.5689_5690del |

p.Leu1897ValfsTer6 |

Ex 17 |

A3 |

1 |

S |

P |

|

c.6006delT

|

p.Phe2002LeufsTer28

|

Ex 19 |

A3 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| c.6146dupG |

p.His2050ThrfsTer3 |

Ex 20 |

C1 |

1 |

Mo |

— |

|

c.6737_6738delAA

|

p.Lys2246ArgfsTer138

|

Ex 25 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

c.6800dupT

|

p.Ser2269IlefsTer116

|

Ex 25 |

C2 |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Large rearrangements

|

| Intron 22 inversion |

— |

Int 22 |

— |

109/5 |

S/U |

P/ N |

| Intron 1 inversion |

— |

Int 1 |

— |

5 |

S |

P/ N |

| Deletion exon 1 |

— |

Ex 1 |

— |

2 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 1-4 |

— |

Ex 1-4 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 4-9 |

— |

Ex 4-9 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Deletion exon 6-22

|

— |

Ex 6-22 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 7 |

— |

Ex 7 |

— |

1 |

Mo |

— |

| Deletion exon 7-13 |

— |

Ex 7-13 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 8-9 |

— |

Ex 8-9 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 14 |

— |

Ex 14 |

— |

3 |

S |

— |

| Deletion exon 22 |

— |

Ex 22 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Deletion exon 22-25

|

— |

Ex 22-25 |

— |

1 |

S |

P |

| Deletion exon 26 |

— |

Ex 26 |

— |

1 |

S |

— |

|

Deletion exon 26 and duplication exon 23-25

|

— |

Ex 23-26 |

— |

1 |

S |

P |

Ex, exon; Int, intron; S, severe; Mo, moderate; Mi, mild; U, unknown; N, negative; P, positive; —, data is not available.

Note: Novel variants are in bold font.

Table 2.

List of Benign/likely, Benign/uncertain Significance Variants Identified in Patients with an Identified Pathogenic/likely Pathogenic Variant

|

Suggested cause of HA in the patient who carries this variant

|

Number of Patients

|

Predicted Pathogenicity

|

ACMG Evidence Codes

|

dbSNP/HGMD ID

|

Amino Acid Change (NP_000123.1)

|

Nucleotide Change (NM_000132.3)

|

| Inversion22 |

1 |

Likely Benign |

BS2, BP4, BP5 |

rs28370201/CS1314199 |

— |

c.266-19G > A |

| Del exon 22 |

1 |

Likely Benign |

BS2, BP4, BP5 |

rs28370236/- |

— |

c.388 + 134G > C |

| Del exon 22 |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM2, BP4, BP5 |

NR |

— |

c.787+158T>C

|

| c.1009 + 1G > A |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM2, BP4, BP5 |

-/CS0911204 |

— |

c.1009 + 3A > T |

| Different variants |

4 |

Benign |

BA1, BP4, BP6, BP5 |

rs7058826/- |

— |

c.1010-27G > A |

| c.1063C > T |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM2, BP4, BP5 |

rs1318036910/- |

— |

c.1271 + 78C > T |

| c.1778T > A |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM2, BP4, BP5 |

NR |

— |

c.1903+44A>C

|

| c.2438_2448del |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM1, PM2, BP7, BP5 |

NR |

p.Leu812 = |

c.2436C>A

|

| c.1596G > A |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM1, PM2, BP7, BP5 |

NR |

p.Asn847 = |

c.2541T>C

|

| c.5263C > T |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM1, PM2, BP7, BP5 |

NR |

p.Leu1080 = |

c.3238C>T

|

| Different variants |

12 |

Benign |

PM1, PP2, BA1, BP4, BP6, BP5 |

rs1800291/CM960556 |

p.Asp1260Glu |

c.3780C > G |

| Different variants |

28 |

Benign |

PM1, BA1, BP6, BP7, BP5 |

NR |

p.Ser1288 = |

c.3864A > C |

| c.1952A > C |

1 |

Uncertain Significance |

PM2, PP2, PP3, BP5 |

rs782055986 |

p.Glu1642Gly |

c.4925A > G |

| c.5263C > T |

1 |

Likely Benign |

PM1, PM2, PP2, BP4, BP5 |

NR |

p.Gln1742Glu |

c.5224C>G

|

| Different variants |

60 |

Benign |

BA1, BP4, BP5 |

rs4898352/- |

— |

c.5998 + 91T > A |

| Del exon 7 |

1 |

Likely Benign |

BS2, BP4, BP5 |

rs782132907/CS141485 |

— |

c.5999-11G > A |

| c.5359G > A |

1 |

Uncertain Significance |

PM1, PM2, PP2, PM5, BP4, BP5 |

NR |

p.His2174Arg |

c.6521A > G |

NR: not reported.

ACMG evidence codes, these codes are based on the 2015 ACMG-AMP guideline.

25

Note: Novel variants are in bold font.

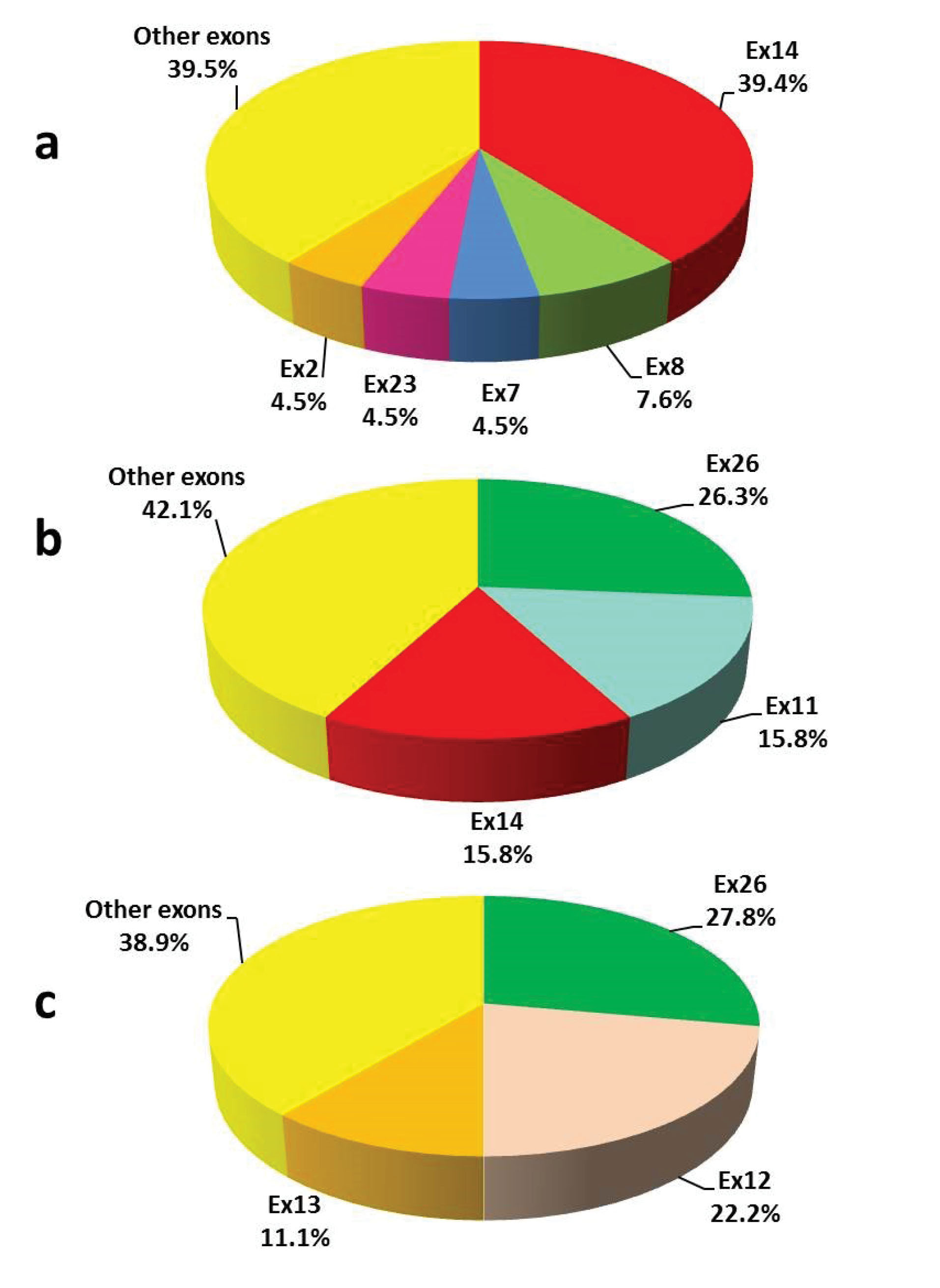

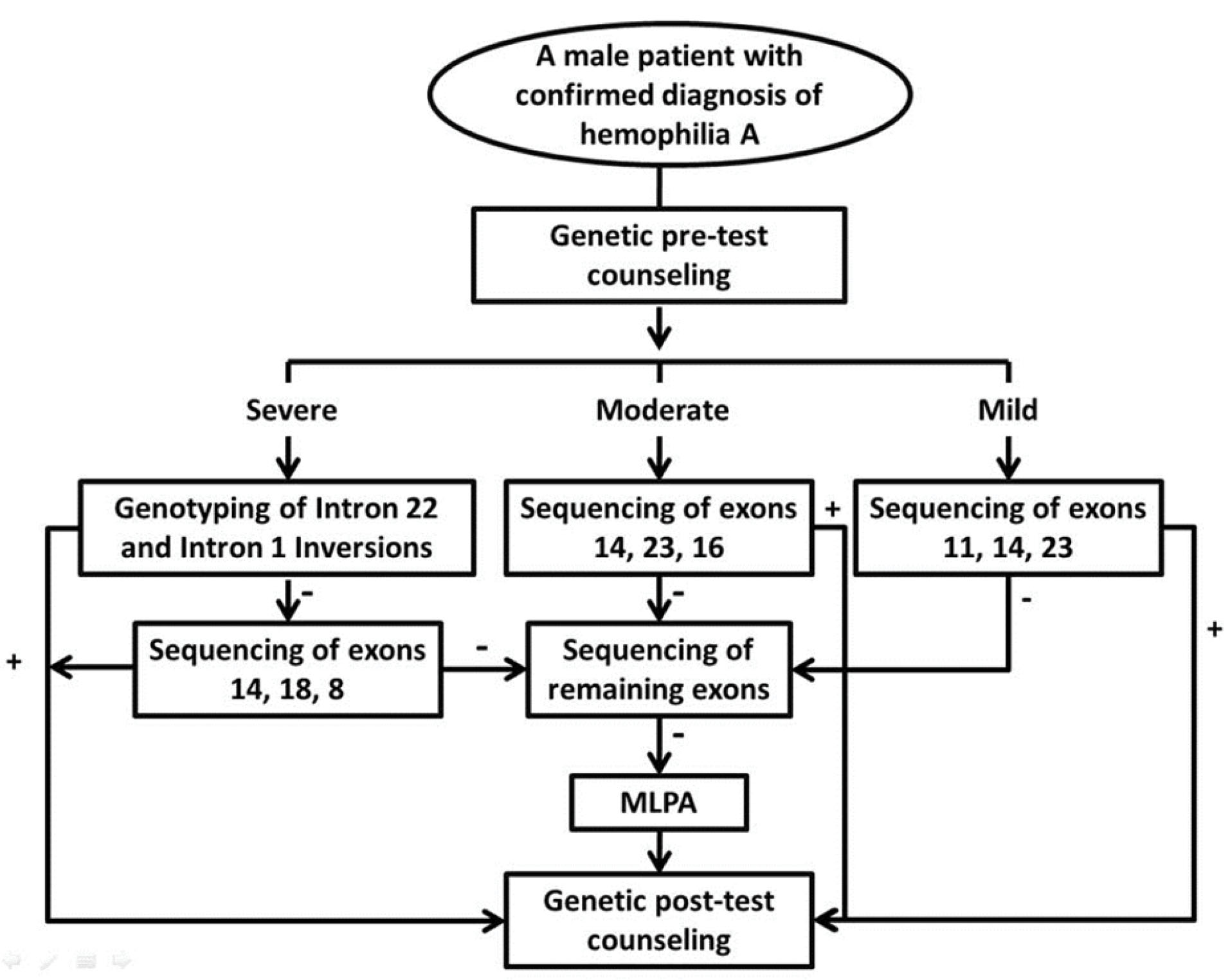

Frequencies of detected point mutations in different exons are also shown in Figure 1. The study of point mutations frequencies in different exons in Iranian severe HA patients whose data were recorded in the EAHAD F8 database showed that exons 14, 8, 16 and 7 had the highest proportion of point mutations in this population, in decreasing order of frequency.13 Study of the frequency of point mutations in different exons in the three populations from North America, Western Europe, and East Asia showed that in all three populations, more than half of the mutations were concentrated in only five exons ofthe gene. In all three populations, exons 11, 14 and 23 in the mild form, exons 14, 23 and 16 in the moderate form and exons 14, 18 and 8 in the severe form were among the first 5 exons that had the highest proportion of point mutations (Table 3). A strategy to decrease the costs of genetic testing of HA was suggested based on this finding (Figure 2). In this algorithm, first, the exons which have the highest contribution to the disease could be investigated and only if no mutation is found, the remaining exons are sequenced.

Table 3.

Exons with the Highest Frequency of Mutations in 3 Mild, Moderate and Severe Forms of HA in 3 Different Populations (North America, Western Europe, and East Asia)

|

|

Northern America

(3235 Cases)

|

Western Europe

(2361 Cases)

|

Eastern Asia

(299 Cases)

|

| Mild |

11 (19.6%), 14 (11.6%), 12 (11.1%), 23 (9.1%), 18 (5.5%) |

23 (15%), 11 (9.9%), 8 (9.4%), 4 (8.3%), 14 (8.3%) |

14 (16.2%), 11 (13.5%), 23 (13.5%), 4 (10.8%), 18 (10.8%) |

| Moderate |

14 (22.7%), 23 (12.4%), 18 (10.2%), 11 (8.9%), 16 (5.1%) |

14 (19.0%), 23 (10.9%), 19 (8.8%), 16 (6.9%), 11 (5.5%) |

14 (23.7%), 23 (16.3%), 16 (10.0%), 13 (7.5%), 3 (5%) |

| Severe |

14 (38.7%), 18 (5.6%), 23 (5.2%), 8 (4.8%), 24 (4.1%) |

14 (41.7%), 23 (4.7%), 18 (4.6%), 8 (4.2%), 24 (3.8%) |

14 (36.1%), 18 (7.1%), 2 (5.9%), 4 (4.7%), 8 (4.7%) |

The percentage of mutations in each exon is shown in parentheses. Exons common between the three populations in each of the three forms of disease are shown by bold font.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Detected Point Mutations in Different Exons and Their Boundary Regions of the F8 Gene in Three Forms of HA; a) Severe, b) Moderate, c) Mild.

.

Distribution of Detected Point Mutations in Different Exons and Their Boundary Regions of the F8 Gene in Three Forms of HA; a) Severe, b) Moderate, c) Mild.

Figure 2.

Suggested Algorithm for Molecular Diagnosis of Patients with HA.

.

Suggested Algorithm for Molecular Diagnosis of Patients with HA.

Analysis of the distribution of pathogenic variants in different domains of factor VIII showed that point mutations in the severe form are more concentrated in the B domain, while in the mild and moderate forms, a higher frequency of these variants was seen in other domains (especially A2 and c2).

In this study, a total of 29 novel pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (five missense, one nonsense, two splice site, 18 small insertion and/or deletion, and three large rearrangements) and six benign/likely benign/ uncertain significance variants were found. These variants were not described in the HA mutation databases or published articles.4

The parental origins of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants for 54 HA families, including 30 families with point mutations and 24 families with genomic rearrangements, are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parental Origin of Pathogenic/likely Pathogenic Variants for 54 HA Families

|

Variants

|

Carrier Mother

|

Non-carrier Mother

|

Total

|

|

Grandfather

|

Grandmother

|

| Inversion 22 type 1 |

13 |

1 |

2 |

16 |

| Inversion 22 type 2 |

3 |

1 |

— |

4 |

| Inversion 1 |

1 |

— |

— |

1 |

| Gross del/dup |

2 |

— |

1 |

3 |

| Point mutation |

14 |

2 |

14 |

30 |

Discussion

In previous studies, the severe form of the disease has been reported as the most abundant form of HA, followed by mild and moderate forms.27,28 However, in contrast to previous studies, in our cases, the severe form was followed by moderate cases in terms of prevalence. A lower frequency of mild cases compared with the moderate may be due to lack of referral for prenatal diagnosis (Iran fetuses with mild phenotype, as seen in other affected family members, cannot be aborted legally) or lack of family desire for genetic analysis or both.

A total of 144 different pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (including 29 novel mutations) were identified, which confirms the high rate of allelic heterogeneity in HA. According to previous reports, the distributions of the different forms of F8 pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants have been shown to be different between the mild, moderate and severe forms. Inv22 and Inv1 mutations were detected in 109 (41.6%) and 5 (1.9 %) severe HA families (Table 1). The frequencies of Inv22 and Inv1 were within the ranges reported in previous studies.1,29,30

In this study, five novel missense variants in exons 15, 16, 17, 22 and 25 were identified. These variants were interpreted as “likely pathogenic” based on two moderate (PM1: variant in a mutational hotspot in F8 gene and PM2: absent in population databases) and two supporting (PP2: missense variant in gene F8 that has 611 pathogenic missense variants out of 635 pathogenic variants and PP3: pathogenic computational predicts) evidence of pathogenicity.18,25 For the three variants c.5558C > A, c.5724G > T and c.6319G > C, there is also an additional evidence of pathogenicity (PM5: another amino-acid missense variant at this position).18,25 Among novel variants, one nonsense and 18 small insertion and/or deletion mutations were interpreted as “pathogenic” based on one very strong (PVS1: Null variant) and two moderate (PM1 and PM2) evidence of pathogenicity.18,25 In addition to the novel point mutations mentioned above, three large rearrangements were also found that affect critical regions of the FVIII protein. Therefore, these variants were also considered to be the cause of HA in the cases with these changes.

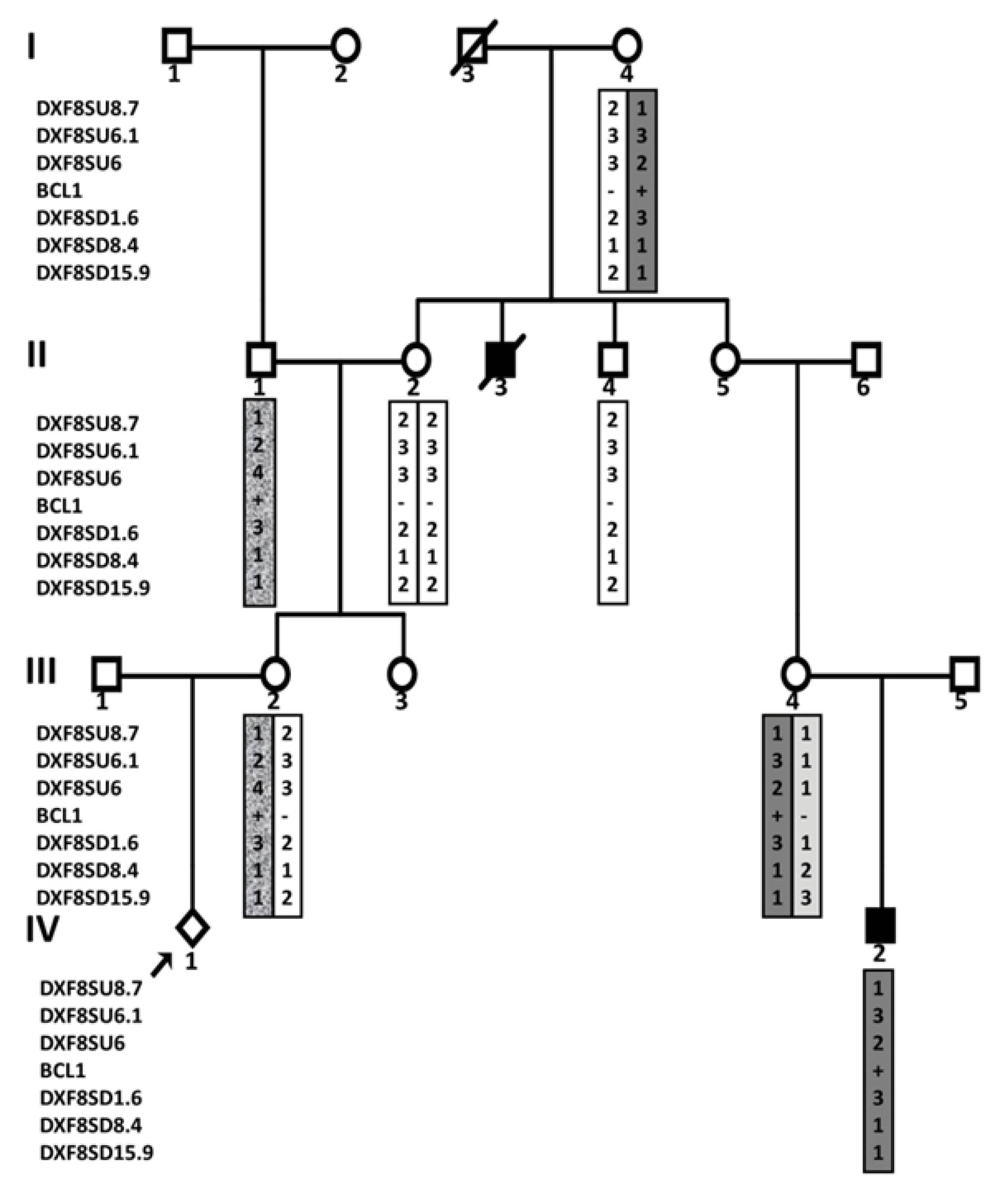

c.1752 + 5dupG was another novel variant that was identified in one patient listed in Table 1. The pedigree of the family is shown in Figure 3 as an example of pedigrees in which STR markers were used to determine the origin of the mutation and also to determine the status of different members in the pedigree. As can be seen, the proband (III-2) was an 11-week pregnant woman who had been referred to our center in 2014 for prenatal diagnosis. Two individuals with HA (II-3 and IV-2) were recorded in this pedigree, based on the couple’s report. Clinical and laboratory information was available only for the IV-2 individual. Sanger sequencing of the F8 gene in IV-2 (which was negative for Inv22&1) was performed simultaneously with indirect screening using STR and RFLP markers. The only variant observed in the affected boy (c.1752 + 5dupG) was not found in his mother. The pathogenicity of this variant is not clear since the claim is that II-3 may be affected by HA (was not registered as hemophilia and was not alive to perform any test and only his family had claimed that he was affected). If this is the case, then it could be argued that a variant other than this change might be the cause of HA. But if the disease was ruled out in the II-3, a de novo mutation in the only person with HA in the family could provide strong evidence of pathogenicity. However, the indirect method showed that the pregnant woman did not have the haplotype observed in the affected boy nor did she have the mutation; so both methods revealed that the risk of HA for the fetus was no greater than the general population.

Figure 3.

A pedigree of an HA family in which STR and RFLP markers were used to determine the origin of the mutation and also to determine the status of different members in the pedigree. Affected individuals are shown shaded.

.

A pedigree of an HA family in which STR and RFLP markers were used to determine the origin of the mutation and also to determine the status of different members in the pedigree. Affected individuals are shown shaded.

Another novel variant was c.143 + 3_143 + 4insT. Despite the sequencing of all exons and promoter region of the F8 gene, no changes other than c.143 + 3_143 + 4insT were identified in this patient. This variant was interpreted as “likely pathogenic” based on (PS4, PM2, PP3, and PP4) evidence of pathogenicity.18,25

For molecular testing, information about benign variants is just as important as information about pathogenic variants. In this study, four benign variants, c.5998 + 91T > A, c.3864A > C (p.Ser1288 = ), c.3780C > G (p.Asp1260Glu) and c.1010-27G > A, were more frequent. Given that non-pathogenic variants were not recorded in all patients, it was not possible to determine the frequency of these variants in the studied population. In addition to the four variants mentioned, 13 other benign/likely benign/ uncertain significance variants (including six novel variants) were observed, each of which was identified in only one patient.

A novel variant c.5359G > A (p.Glu1787Lys) and a reported variant c.6521A > G (p.His2174Arg) were identified in exons 15 and 22, both together in an individual with moderate hemophilia. No variant has been reported so far in codon 1787, but amino acid substitution, from histidine to residues with different properties (leucine/aspartic/tyrosine) at position 2174 has been reported previously.31-34 The variant c.5359G > A results in a substitution of an acidic residue (Glu) for a basic residue (Lys) but c.6521A > G replaces one amino acid with another amino acid in the same amino acid group. Therefore, although variant c.6521A > G has already been reported as a pathogenic variant in the f8-db.eahad.org database, it can be suggested that based on two moderate and two supporting evidence of pathogenicity (PM1 PM2 PP2 PP3), the c.5359G > A (p.Glu1787Lys) variant is the cause of the disease. Therefore, the variant c.5359G > A was listed in Table 1. A study of individuals with each of these changes alone can provide more information about the effect of each of these variants.

A co-occurrence of two previously reported variants, c.1952A > C (p.His651Pro) and c.4925A > G (p.Glu1642Gly), were also identified in one patient with severe HA. Each of these changes had been previously reported separately in two individuals with a moderate form of the disease (c.4925A > G in an Iranian and c.1952A > C in a Canadian patient).11,35 Computational algorithms predict conflicting effects of these variants on protein structure and function. The histidine at position 651 is conserved across species and the variant c.1952A > C is reported in ClinVar as a likely pathogenic variant but the evidence is not sufficient to classify c.4925A > G (in the B domain) as a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant. According to the previous studies, the B domain is not necessary for FVIII procoagulant function. Therefore, the c.4925A > G in this domain is not expected to cause loss of function. It is suggested that the variant c.1952A > C, based on two moderate and three supporting evidence of pathogenicity (PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3, and PP5), could be considered as the cause of the disease and the latter change may be considered as a modifier or a neutral variant. More studies on these variants, alone or in combination with each other, is needed.36

Direct sequencing of Inv22&1- negative severe HA cases showed that although pathogenic variants detectable by Sanger sequencing are scattered in the different exons, they are concentrated in exons 14 (39.4%), 8 (7.6%), 7 (4.5%), 2 (4.5%) and 23 (4.5%) (Figure 1). More than half of the pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants are accumulated in the three exons 26 (26.3%), 11 (15.8%), and 14 (15.8%) in the moderate form, and in the three exons 26 (27.8%), 12 (22.2%), and 13 (11.1%) in the mild form. In 2005 and 2007, Bogdanova et al reported molecular studies on 86 Inv22&1- negative severe HA, 23 moderate and 112 mild HA cases.37,38 They reported that more than half of the identified mutations in severe HA cases were in exon 14, while about half of the variants identified in mild and moderate forms were in exons 11 and 23. In the majority of molecular studies on HA, the distribution of different variants in the F8 gene exons has been examined and the frequency of each of the variants is less discussed.4

Although modern sequencing technologies are already in use in many countries and may eventually substitute the traditional approaches in the near future, these methods are not yet used routinely in developing and transition countries; therefore, it seems that suggestion of a cost-effective strategy would be worthwhile for centers using Sanger sequencing to detect F8 point mutations. This study showed that depending on the severity of HA, the order of Sanger sequencing of the exons can be different. To determine whether the specific strategy should be considered for each population, the frequency of point mutations in different exons in the three populations was compared. This comparison showed that although the pattern of distribution of mutations in different exons among these populations is not the same, for all three severe, moderate, and mild forms, there are at least three exons that are common between the three populations among the exons with the highest mutation frequency. Based on these results, an algorithm applicable to populations from different continents was proposed (Figure 2).

Given the different pattern observed for the distribution of mutations in different exons of the F8 gene in the Iranian population compared to the other populations, it is suggested that, depending on the form of the disease, the combination of the suggested exons in the algorithm and the exons with the highest frequency of mutation should be examined first. It is clear that more Iranian patients should be considered to find the best strategy for this country.

Despite genetic screening of the entire coding region, promoter and exon-intron boundaries using direct sequencing, introns 22 and 1 inversion by inverse shifting PCR and large insertion and/or deletions by MLPA, no pathogenic variant was found in five cases. Pathogenic variants outside the investigated regions (deep intronic or regulatory regions far from the F8 gene), structural variants as well as misdiagnosis, can account for this finding. In previous studies, it was also reported that a percentage of patients remain undiagnosed.29,39-41

The majority of variants (94.5%) were associated with only one form of HA (severe or moderate or mild) but for eight variants (5.5% of variants), variable severity was found. Modifier genes and environmental factors may play a role in phenotypic heterogeneity.4,42

Determination of the parental origin of F8 pathogenic variants in pedigrees is one of the important issues in carrier detection and PND for HA. Molecular analysis of the F8 gene combined with linkage analysis using genetic markers can be useful in this regard. In this group, the majority (21/24, 87.5%) of genomic rearrangements including inversions and deletions/duplications of one or multiple exons were inherited from a carrier mother but about half (14/30, 46.7%) of the point mutations were de novo. This finding is in accordance with the results of previous studies.43,44

In conclusion, the results of a molecular study on 329 unrelated Iranian HA families are presented here. According to the literature, this is the most comprehensive molecular analysis of HA families in Iran and provides deep aspects of the molecular basis of the disease. The results of the study can help genetic labs to choose the most appropriate diagnostic workflow for HA and provides information for genetic counseling of the families.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully thank the families who took the time to contribute to this study. We also gratefully thank Dr. Zeinali Medical Genetics Lab staff for helping us to conduct this study.

Authors’ Contribution

SA, FR, FZ, MJ, PGhT, TSh and HB performed the research. SA and EDD analyzed the data and designed the research study. SA, MK, EDD, and SZ wrote the paper. All authors contributed to drafting the work and approving the submitted paper and they agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

SZ has shares in Genetek Biopharma which is mentioned and provided the GT Hapscreen kit for the study. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kawsar Human Genetics Research Center, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Antonarakis SE, Kazazian HH, Tuddenham EG. Molecular etiology of factor VIII deficiency in hemophilia A. Hum Mutat 1995; 5(1):1-22. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380050102 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Wang L, Wang H. The protein structure and effect of factor VIII. Thromb Res 2007; 119(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.12.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gitschier J, Drayna D, Tuddenham EG, White RL, Lawn RM. Genetic mapping and diagnosis of haemophilia A achieved through a BclI polymorphism in the factor VIII gene. Nature 1985; 314(6013):738-40. doi: 10.1038/314738a0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Payne AB, Miller CH, Kelly FM, Michael Soucie J, Craig Hooper W. The CDC Hemophilia A Mutation Project (CHAMP) mutation list: a new online resource. Hum Mutat 2013; 34(2):E2382-91. doi: 10.1002/humu.22247 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Li Q, Shi P, Liu N, Kong X, Guo R. Mutation analysis in the F8 gene in 485 families with haemophilia A and prenatal diagnosis in China. Haemophilia 2021; 27(1):e88-e92. doi: 10.1111/hae.14206 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- González-Ramos IA, Mantilla-Capacho JM, Luna-Záizar H, Mundo-Ayala JN, Lara-Navarro IJ, Ornelas-Ricardo D. Genetic analysis for carrier diagnosis in hemophilia A and B in the Mexican population: 25 years of experience. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2020; 184(4):939-54. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yi S, Zuo Y, Yu Q, Yang Q, Li M, Lan Y. A novel splicing mutation in F8 causes various aberrant transcripts in a hemophilia A patient and identifies a new transcript from healthy individuals. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2020; 31(8):506-10. doi: 10.1097/mbc.0000000000000952 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peake IR, Lillicrap DP, Boulyjenkov V, Briet E, Chan V, Ginter EK. Haemophilia: strategies for carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis. Bull World Health Organ 1993; 71(3-4):429-58. [ Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh M, Kardoost M, Zamani G, Baghaeepour MR, Sadeghian K, Pourhoseingholi MA. Occurrence of haemophilia in Iran. Haemophilia 2009; 15(1):348-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01874.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dorgalaleh A, Dadashizadeh G, Bamedi T. Hemophilia in Iran. Hematology 2016; 21(5):300-10. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2015.1125080 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Onsori H, Feizi MA, Feizi AA. A novel mutation (4040-4045 nt delA) in exon 14 of the factor VIII gene causing severe hemophilia A. Indian J Hum Genet 2011; 17(3):232-4. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.92095 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rafati M, Ravanbod S, Hoseini A, Rassoulzadegan M, Jazebi M, Enayat MS. Identification of ten large deletions and one duplication in the F8 gene of eleven unrelated Iranian severe haemophilia A families using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification technique. Haemophilia 2011; 17(4):705-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02476.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ravanbod S, Rassoulzadegan M, Rastegar-Lari G, Jazebi M, Enayat MS, Ala F. Identification of 123 previously unreported mutations in the F8 gene of Iranian patients with haemophilia A. Haemophilia 2012; 18(3):e340-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02708.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16(3):1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mousavi SH, Mesbah-Namin SA, Rezaie N, Zeinali S. Frequencies of intron 1 and 22 inversions of factor VIII gene: a first report in Afghan patients with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia 2018; 24(3):e157-e60. doi: 10.1111/hae.13491 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rossetti LC, Radic CP, Larripa IB, De Brasi CD. Developing a new generation of tests for genotyping hemophilia-causative rearrangements involving int22h and int1h hotspots in the factor VIII gene. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6(5):830-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02926.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kopanos C, Tsiolkas V, Kouris A, Chapple CE, Albarca Aguilera M, Meyer R. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2019; 35(11):1978-80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, Jang W, Rubinstein WS, Church DM. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42(Database issue):D980-5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29(1):308-11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS. Human gene mutation database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat 2003; 21(6):577-81. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2013;Chapter 7:Unit7.20. 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 2014; 46(3):310-5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31(13):3812-4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods 2014; 11(4):361-2. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015; 17(5):405-24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Richards B, Heilig R, Oberlé I, Storjohann L, Horn GT. Rapid PCR analysis of the St14 (DXS52) VNTR. Nucleic Acids Res 1991; 19(8):1944. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.8.1944 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Den Uijl IE, Mauser Bunschoten EP, Roosendaal G, Schutgens RE, Biesma DH, Grobbee DE. Clinical severity of haemophilia A: does the classification of the 1950s still stand?. Haemophilia 2011; 17(6):849-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02539.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eshghi P, Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Karimi M, Aghighi M. Haemophilia in the developing countries: the Iranian experience. Arch Med Sci 2010; 6(1):83-9. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.13512 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Yang L, Qin X, Liu X, Zhang Y. Spectrum of molecular defects in 216 Chinese families with hemophilia A: identification of noninversion mutation hot spots and 42 novel mutations. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2018; 24(1):70-8. doi: 10.1177/1076029616687848 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bagnall RD, Waseem N, Green PM, Giannelli F. Recurrent inversion breaking intron 1 of the factor VIII gene is a frequent cause of severe hemophilia A. Blood 2002; 99(1):168-74. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.168 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Johnsen JM, Fletcher SN, Huston H, Roberge S, Martin BK, Kircher M. Novel approach to genetic analysis and results in 3000 hemophilia patients enrolled in the My Life, Our Future initiative. Blood Adv 2017; 1(13):824-34. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016002923 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Debeljak M, Kitanovski L, Trampuš Bakija A, Benedik Dolničar M. Spectrum of F8 gene mutations in haemophilia A patients from Slovenia. Haemophilia 2012; 18(6):e420-3. doi: 10.1111/hae.12003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Habart D, Kalabova D, Novotny M, Vorlova Z. Thirty-four novel mutations detected in factor VIII gene by multiplex CSGE: modeling of 13 novel amino acid substitutions. J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1(4):773-81. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00149.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Repessé Y, Slaoui M, Ferrandiz D, Gautier P, Costa C, Costa JM. Factor VIII (FVIII) gene mutations in 120 patients with hemophilia A: detection of 26 novel mutations and correlation with FVIII inhibitor development. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(7):1469-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02591.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rydz N, Leggo J, Tinlin S, James P, Lillicrap D. The Canadian “National Program for hemophilia mutation testing” database: a ten-year review. Am J Hematol 2013; 88(12):1030-4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23557 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ogata K, Selvaraj SR, Miao HZ, Pipe SW. Most factor VIII B domain missense mutations are unlikely to be causative mutations for severe hemophilia A: implications for genotyping. J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9(6):1183-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04268.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova N, Markoff A, Eisert R, Wermes C, Pollmann H, Todorova A. Spectrum of molecular defects and mutation detection rate in patients with mild and moderate hemophilia A. Hum Mutat 2007; 28(1):54-60. doi: 10.1002/humu.20403 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova N, Markoff A, Pollmann H, Nowak-Göttl U, Eisert R, Wermes C. Spectrum of molecular defects and mutation detection rate in patients with severe hemophilia A. Hum Mutat 2005; 26(3):249-54. doi: 10.1002/humu.20208 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abdi M, Zemani-Fodil F, Fodil M, Aberkane MS, Touhami H, Saidi-Mehtar N. First molecular analysis of F8 gene in Algeria: identification of two novel mutations. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2014; 20(7):741-8. doi: 10.1177/1076029613513321 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Klopp N, Oldenburg J, Uen C, Schneppenheim R, Graw J. 11 hemophilia A patients without mutations in the factor VIII encoding gene. Thromb Haemost 2002; 88(2):357-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1613212 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lassalle F, Jourdy Y, Jouan L, Swystun L, Gauthier J, Zawadzki C. The challenge of genetically unresolved haemophilia A patients: interest of the combination of whole F8 gene sequencing and functional assays. Haemophilia 2020; 26(6):1056-63. doi: 10.1111/hae.14179 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Masood Khan MT, Taj AS. Genotype-phenotype heterogeneity in haemophilia. In: Abrol P, ed. Hemophilia-Recent Advances. IntechOpen; 2019. 10.5772/intechopen.81429

- Lu Y, Xin Y, Dai J, Wu X, You G, Ding Q. Spectrum and origin of mutations in sporadic cases of haemophilia A in China. Haemophilia 2018; 24(2):291-8. doi: 10.1111/hae.13402 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ljung RC, Sjörin E. Origin of mutation in sporadic cases of haemophilia A. Br J Haematol 1999; 106(4):870-4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01631.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]